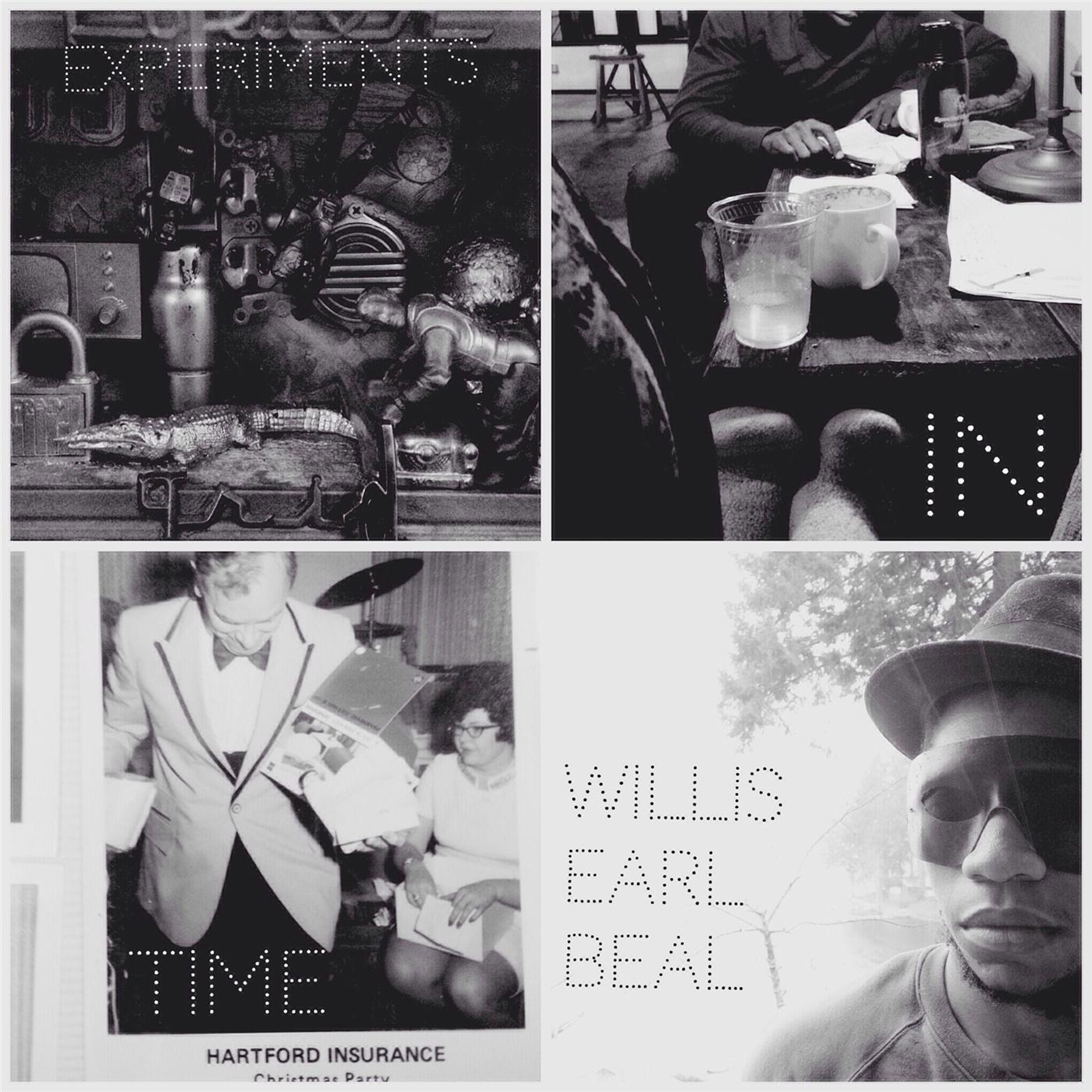

Willis Earl Beal Speaks On New Album “Experiments In Time,” Upcoming Film “Memphis,” And More

08.15.2014

MUSIC

Most artists, especially in discussing their music, declare a disdain for being categorized, simplified or placed in a genre box. Willis Earl Beal makes sure there is no mistake about it and failed attempts to define him over the years– musically and socially – are what have made him the person he is today.

Beal has never been one for being pigeonholed; in many ways, he has essentially lived in his own world since he was a child either voluntarily or simply by way of being unaccepted by the surrounding environment. Thus, his third album, Experiments In Time, is his latest attempt to make sense of the universe. “I can’t talk to anybody most of the time. I feel very alone, with the exception of my wife,” he says. “I want to make the listener feel as if they are having a conversation with me. I make music for the people who hear it and get it and instantaneously have a connection with it. I want people to feel they have a friend or companion.”

“For me, a recording is a way of capturing time. Every song that I have or piece of clothing that I have, I can attach a direct time and story to it.” In the case of Experiments – which he released independently – he continues, “I transitioned from New York to Washington [State], so the ethereal nature, the airiness of the record has a lot to do with my transition from a big city to [a place] where there’s trees all around.”

Life+Times spoke with Beal about Experiments In Time, the upcoming film Memphis that he scored and stars in, where he’s from, and more.

L+T: Where did the title Experiments In Time come from and how do the songs you selected embody that?

Willis Earl Beal: The title came from this book I read called Experiments With Time. I read that book a long time ago. The reason I chose that title and the songs was that I wanted to talk about the non-locality of time and how you can never really grasp it, yet it’s always a factor. The record sounds the way it does because of the static in my brain. So, the process and the execution have a semiotic relationship; what I mean is, the process is I’m recording with home equipment and I go very slowly. The way the recording sounds is how my life is day to day, it’s very lethargic. It just so happens that I use equipment and a process that doesn’t allow for the static to not be there. The static on the record is equivalent to the static in my mind.

L+T: You’ve called this a “grey and white” album and have talked in the past about your synesthesia. Expand on that.

WEB: When I think about static, I think about grey. When I think about the idea of time, I feel like time is grey-colored. It’s more intuitive than anything. So, that’s the reason why it’s a greyish-white album. In addition to that, the sound waves; a lot of times, when you sing a certain way they’ll say it’s blue or something. I think that’s where the blues delves from. When people hear the blues, they get this blue-colored feeling and that feeling means that it’s somber. But when I think about grey, I think about a middle ground, kind of a purgatory – not a sadness, not a happiness, just a non-place, a non-entity, something that’s not really grounded high or low. That’s why I feel that this is a great record. Especially a song like “In Your Hand,” that’s a very greyish-white song. Also, it helps that here in Washington it was grey skies. When I recorded the record it was winter and rained every single day. I recorded a record prior to this called A Place That Doesn’t Exist and that’s actually gold because I recorded it in the summertime. It all depends on the environment that the record was recorded in.

L+T: You’re originally from Chicago. You’ve been in New York, Washington and other places, too, but what part of Chicago are you from and what role has that played in making you the person and artist that you are today?

WEB: Being in Chicago was very difficult for me. Everything factors into your development, but being in Chicago, I think the only thing I can thank it for is rejecting me so that I could leave and go someplace else. I grew up on the South Side of Chicago in Englewood. I moved around a lot – my mother lived up north for awhile and on the West Side – but my grandmother stayed on the South Side and that’s where I spent most of my time. The South Side has never been a place that’s very welcoming for creative people who want to be expansive and think about something other than making a buck. I felt really alone around there; I couldn’t really make any friends and I knew not to try. I would go out and play basketball and shit like that, but for the most part it was just a hostile environment. Then I went up north with the white people, and I found that even though they were a lot more accepting of creative types, it was still this very cold environment. When I used to do open mics, read my poetry and shit like that, I found it to be a totally pretentious scene. Maybe I was the one that was pretentious, I don’t know, but I just couldn’t dig it. I felt like if I stayed in Chicago, I wouldn’t be talking to you now. I would have never felt confident enough to touch an instrument. I love my family, but being around my family was detrimental to any process I would develop later on. I really don’t even consider myself to be from Chicago. A lot of people that are from big cities claim it like, “Oh yeah, the big city influenced me, shout out to the Chi,” but I never related and always felt like I should have been somewhere else. When I would be in Chicago – and, really, everywhere I’ve gone – people have always asked me, “Where are you from? Because you’re obviously not from around here.” The way in which I’m special is that I’m not really from anywhere, you know.

L+T: Where did you go that allowed you to find and maximize your creativity?

WEB: Albuquerque, New Mexico. I went down there after I got fired from my job at the [then-]Sears Tower. I swear it was like the 25th job I had lost, including the military. So, I just took my last paycheck, gave my grandmother part of it and took the rest and took a bus down there. That started the whole odyssey. Up to that point, I hadn’t touched an instrument, keyboard, guitar, hadn’t sang any songs. I grew up listening Sade and Michael Jackson in my family like everybody else, but I didn’t really have any musical interest prior to going to Albuquerque. I just felt like there was something out there for me and I don’t know what. I saw it in a movie and it was just clear that that’s where I needed to go.

L+T: What were the instruments that you picked up?

WEB: It was a long time before I got in a position to be leisurely enough to even touch an instrument. My initial instrument was my voice. When I was on the streets for a little while, I would see a guy playing a guitar on a Friday or Saturday, and he wouldn’t be getting too many looks or listens…nobody cared. So, I said, “Let me sing for you and make you some money.” I started doing that and noticed that people would stop. By the time I finally got off the street and got an apartment, I got a guitar. I found one at the thrift store. I tried to go learn the thing and got bored with it, they were trying to teach me how to play “Bobby Blue Bland” or something, I don’t know. It didn’t interest me too much. I was thinking, “How can I make this work for me?” So, I started overdubbing – I would take the guitar and a couple of boom boxes with cassette tape decks and record different rudimentary riffs and play them all at the same time while I had the mic and put it all on one tape. Then I would take to get it turned into a CD and it would sound like shit. But that’s what I did.

L+T: What’s the story behind your mask?

WEB: I started wearing the mask toward the middle of me being with Hot Charity [Recordings] when I realized I was going to a lot of photo shoots. It was all for my own good, but what I felt was that people were characterizing me as a Black artist, a bluesman and that sort of thing. I never considered myself to be a blues singer, and obviously, I don’t consider myself to be a Black artist. First of all, I’m not Black, I’m brown [laughs]. I’ve never [met] a Black person before. Second, whether I’m Black, brown, blue or green, why do I need to be characterized as a Black artist? I realized that it’s just my face. You put my face up there, and before I even say a word, people have already got it figured out. So, I put on the mask – it doesn’t obscure my entire face, you know my nationality and ethnicity, but you question my motives. If you’re interested to find out, it causes you to think, “Well, his ethnicity is this, but what the fuck is the mask for?” It starts a discussion and helps me to transcend my race. It’s amazing that that’s still a problem. I’m not saying there are people that are outright racist, but they are quick to pigeonhole an artist, especially when they’re doing something other than rap or straight-ahead R&B. If you’re not going rap, you’re going to be called a Black artist; but if you’re doing rap, that’s what they expect so they’re not going to call you a Black artist. That’s what the mask is all about, along with identity. I never felt like a real person. I’d try to interact and talk to people and I felt like I was acting in a way. So, a lot of times, I feel more authentic when I’m wearing a mask onstage or in public than I do with my regular face.

L+T: The movie Memphis which you star in and scored officially comes out next month. How did you come to be in the film and how was your experience?

WEB: My manager at the time got an inquiry from [director] Tim Sutton. He showed me a clip from his other film Pavilion, and there was a girl with a sparkler – it was a gif – and I knew I wanted to be in the film. I met the guy, we talked about films and liked a lot of the same stuff. So, we agreed that I would do the film. We went down to Memphis and we thought it was going to be a seamless process, because the character was basically a version of me. He was a character that seemed to be lost and was a musician, and he had some success, but that success had fallen off. So, I kind of felt like I could relate to that. Once I started it, it was very, very difficult. I found myself being implanted back into the kind of environment that I left; it was a poor area of Memphis, Black people, I was back in the Black, gospel church and I was alienated. On top of that, the whole crew was white. They’re all going around these areas in search of “authenticity,” I’m there, like, insurgent, because I’m the only Black dude, and I’m staying in a house by myself. When they get ready for me, we go down to the poor Black neighborhood where we’re filming – I’m not trying to make them look bad, they were totally respectful, all of that – but I felt like I was exploiting myself and I started to lose my desire to be in the project. As a result of that, Tim and I argued. I damn near quit the thing and they damn near fired me, rightfully so. But what ended up occurring is we talked about it, and everything you see in the film is a result of the turmoil and then inevitable peace that occurred. At the end of the filming, we did a bonfire, everybody came over, I played them the song I had written [while in Memphis], “Now Is Gone,” and it was great. I was a better person for having done the film. Being in the process of filming the film was a microcosm for the entire life that I had lived. It was very weird, very hard, but I’m glad I did it.

Experiments In Time is available now and Memphis comes out September 25th.