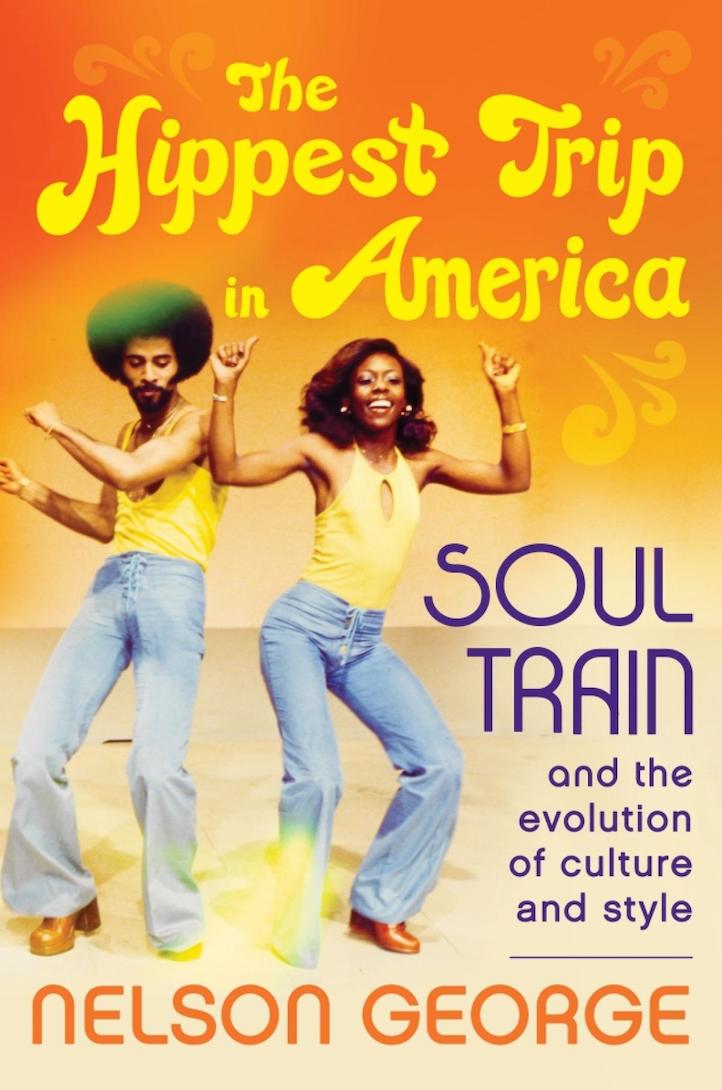

Author Nelson George Talks New Soul Train Book “The Hippest Trip In America”

03.26.2014

MUSIC

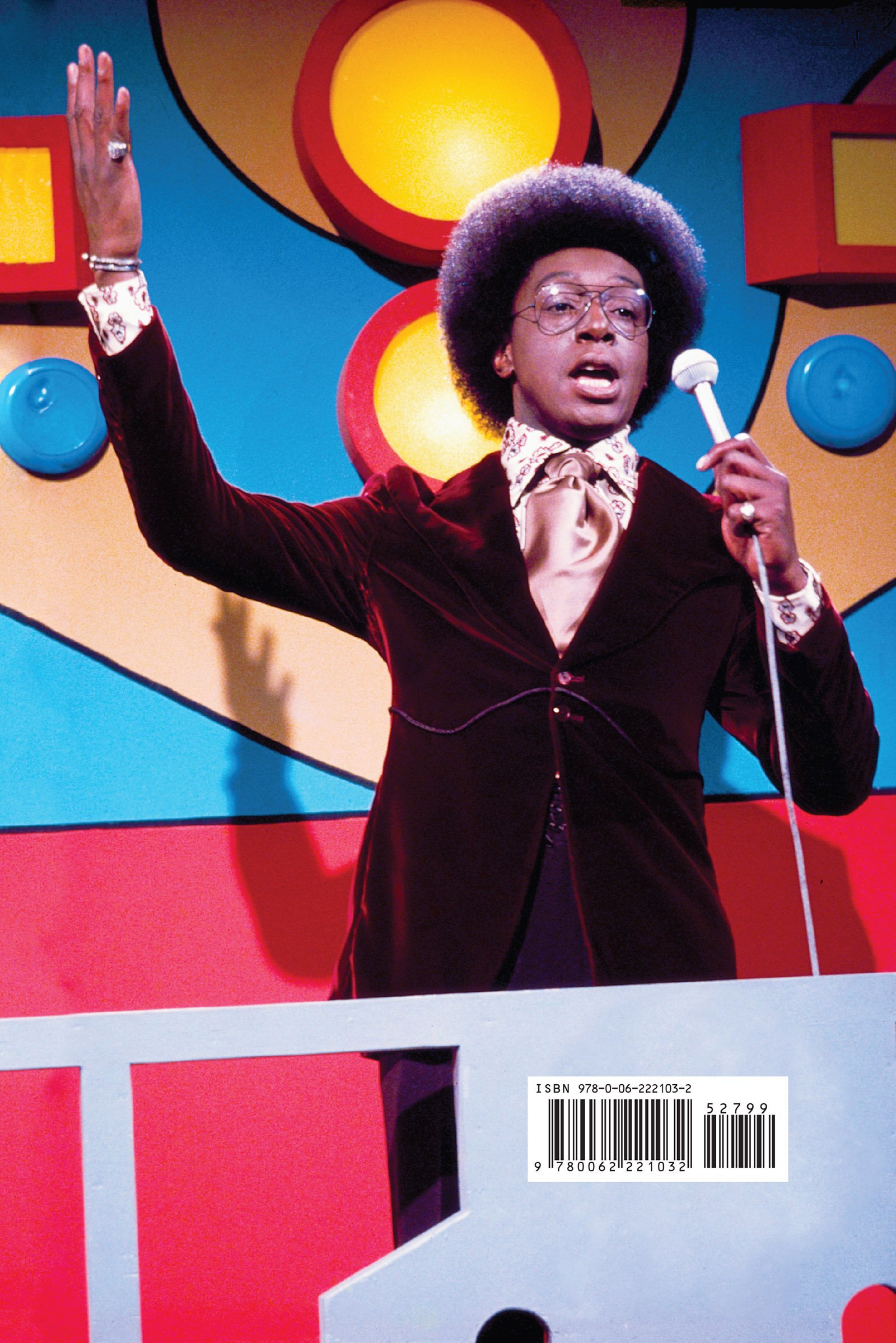

For over three decades, Soul Train was not just a platform to stay up on the latest trends in popular music, but an educational crash course in style, fashion, dance and culture. The brainchild of Don Cornelius, the show according to him, wasn’t much of an anomaly at all; “People look at Soul Train on its surface and assume that it was a tremendous challenge. That it was real hard, and it was almost impossible, and you almost had to kill somebody, but it wasn’t. It wasn’t any of that. Television again is a medium where if you come up with a good idea, it just goes right on…you can always find the right support if the idea is strong enough, and Soul Train was apparently a very strong idea.”

As easy as Cornelius made it sound, given its lasting cultural impact globally, it had to be a bit more complex than that. Hence, author and filmmaker Nelson George deftly takes on the task of whittling that 30 years of history down to a couple hundred easy-to-read pages in his latest work The Hippest Trip In America: Soul Train and the Evolution of Culture and Style (available now). George uses several interviews, including Cornelius, along with plenty of research to provide layered insight into of one of the longest running syndicated shows in television history. He also makes a point to highlight the unsung stars of the show – the dancers.

“One of the things I wanted to do in the book was focus on the dancers,” said George. “I felt like they were these people who had such a profound effect: Cheryl Song, Damito Jo, Don Campbell, etc. People knew their names is some respects, but there was very little [information] around about who these people were, and the world of Soul Train is relative – how people got on the show, the parties they went to, how they bonded, how did it change their everyday life. So, I wanted to make the dancers a huge part of the narrative, so that was one of the focuses of the book.” Life+Times spoke with George to discuss his newest book and the legacy of Soul Train.

Life+Times: What role did Soul Train have in presenting positive images of African-Americans to a national audience?

Nelson George: If you look at the year Soul Train began – 1971 – there was no regularly scheduled show about Black people on TV. There were very few Black supporting roles on any network show. You had the odd Clarence Williams on The Mod Squad, there was Room 222, but they were few and far between. The Black sitcoms came after Soul Train, and the news coverage about Black people tended to be about marches, disruption, trying to explain the “Negro problem.” So, there was virtually no consistent images of Black people as human beings and not as problems, agitators or questions. So, what Don’s show did, number one, was bring Black joy to the world – I don’t think you can leave the world out of this discussion because the legacy of Soul Train internationally is very powerful. Black joy – the fact that Black people had a good time and there was something very spirited and wonderful about our sense of celebration, style, movement, humanity with each other – Soul Train brought that into American households on a regular basis from 1971 well into the 21st century. It has an unprecedented legacy as one of the longest running shows in TV history; particularly, I would say, during the era from the beginning of 1971 until the mid-to-late ‘90s, it was still a very vital place to expose Black music and Black dance and Black style.

L+T: You give a lot of attention to the dancers. Nick Cannon was one of the dancers on the show, which a lot of people don’t know. Was it hard to track them down?

NG: The book was commissioned after Don Cornelius died, and I was really concerned that I wouldn’t have a chance to interview him and get a lot of details that only he would have. Fortunately, VH1 and Kevin Swain who directed the [2010] Soul Train documentary gave me access to a lot of their transcripts, most of which didn’t make it onto the show, including their big interview with Don. So I was able to tap into that. I also got the names of a lot of people through transcripts where they would follow up with Tyrone Proctor, Marco De Santiago and others who were essential to the show but not stars in their own right. They were inside that universe. What was interesting to me was how many of them have continued on to have a legacy. Tyrone is an excellent example. He’s one of the people who popularized “waack dancing.” Now, he lives in Harlem and he travels around the world teaching that dance. He just came back from Argentina, he went to Russia last year, he’s got a trip planned to go to Hong Kong. We’re talking about a dance from 1971, ’72, ’73’, ’74 that he’s still teaching in 2014. It’s remarkable to me how much these dancers have maintained a mystique and still are very active traveling the globe in some cases. Soul Train’s impact and relevance continues on on a global basis. That was something I wasn’t sure about that was totally confirmed by the interviews I did.

L+T: Taking the style, images, dances and artists that were on the show, to you, what has been the most lasting influence of Soul Train?

NG: I think the combination of style and dance. I saw a commercial on TV this year that ran during sports season that was talking about the different eras of fashion, and when it went to the ‘70s, there was a Soul Train line going down. When Daft Punk had their album that went on to win [Grammy Album of The Year], there were tons of videos floating around the internet where Soul Train footage was cut into [their songs]. There’s something about the dancing, the locking, the popping, waacking, and the style which was very colorful. Ironically, the Afro is back, the natural is back, and some of the outfits you might see on some of the Soul Train footage now looks almost contemporary, depending on the crowd. It’s the combination of style and dance together, I think, that has made it so enduring.

L+T: Coming up watching the show and later doing lots of research, what are some of your personal most memorable moments or performances?

NG: There’s a bunch. Writing the book, one of the things I hope it is is a guide to your YouTube viewing. I tried to be very specific about the show numbers, what years certain things happened, so that you can go back and look at episodes as I looked back. Most memorable? Wow. It still tickles me when Don Cornelius and Marvin Gaye had a one-on-one basketball game and Smokey Robinson was the referee. It was like you got the entree to the off-stage world of Black celebrity life in LA at that time, because Marvin, Smokey and Don were tight. So this was sort of like an entry into a world you don’t normally see. There’s so many great moments on that show. I think James Brown doing “Payback,” there’s some incredible Sly Stone performances, Al Green performing after he got injured. Unlike American Bandstand and most of the music dance shows from the ‘60s and ‘70s, Don allowed artists to perform live. So these aren’t just artists lip-synching, they’ve got full bands plugged in. Barry White had his whole Love Unlimited Orchestra on there at one point. You’re not just getting a TV performance, you’re getting a concert-level performance.

L+T: You talk a lot about Don Cornelius’ “cool.” Looking through some clips, I’ve only found one instance of him actually dancing and coming down the Soul Train line. Is that the only one you’ve seen? You have these dancers who are so stylish and wearing colorful clothes, then there’s him whom several people you interviewed referred to as almost like an older father watching the party.

NG: He danced with Mary Wilson of The Supremes one time, and he actually moves well. People who saw Don dance said he had great rhythm and style. He danced, you know, Chicago style, which wasn’t as frantic and is much more laid back than what the Soul Train dancers were doing. He wasn’t super-warm, he was a relatively distant figure to most of the dancers. He had to warm up to you and decide that he wanted to bring you in, you just didn’t come in and become a friend of Don because you were on the show. There was also another side to him. He had parties where he invited some of the Soul Train dancers out to these Hollywood dinners, but Don himself kept a professional distance from the dancers. He was a super-reserved guy, I interviewed him a few times over the years and you always felt like Don was checking you out, taking you in, observing you. He would be cordial and give you straight answers, but he wasn’t your buddy, and that was a big part of his persona.

L+T: There is a chapter in the book specifically about ?uestlove and there are quotes from him throughout. He’s one of the Soul Train aficionados like you. How is it having a conversation with ?uest about Soul Train?

NG: His connection to it is as deep as anyone I’ve ever met. As he says in the book, he comes from a musical family. His mother and father were musicians and he was playing drums at an early age. Not all musicians, unfortunately, are historians of the music they play. A lot of musicians know one or two bands that they really like, but they don’t the breadth; particularly in Black music, you’re talking about a pretty wide expanse of music. He is one of the few people who is plugged in –he’s as much of a historian as he is a musician – so I feel like Soul Train was an essential experience for him in terms of expanding his knowledge and curiosity. He talked about the fact that there’s things he saw on Soul Train that affect how The Roots perform. One of my favorite parties in New York is his Soul Train Valentine’s Day party. I’m always impressed with how much music he knows and how he makes connections. If you look at the lineup for Soul Train shows, it was a pretty eclectic group, so if you watched Soul Train pretty consistently, even if you were just a fan of contemporary dance music, you got a pretty wide understanding of popular music and I think ?uestlove’s career is a reflection of that.

L+T: You mention how the show was never co-opted as happens to many things that come from the African-American community. You also talked about Dick Clark’s Soul Unlimited and something many people don’t know: Jesse Jackson and others were involved in getting that show canceled, even organizing a boycott.

NG: One of the most important people in Black music history has been Clarence Avant. He’s been the Black godfather since the ‘60s. He’s a powerful behind-the-scenes figure. He was an early supporter of Don when he came to LA and he had a relationship with ABC, so when Dick Clark did Soul Unlimited and attempted to, in a sense, run Soul Train off the air, Clarence had a meeting with ABC and the powers that be and helped, along with the boycott, to shut that show down. That was crucial in keeping Soul Train alive. In that early period – ’71, ’72, ’73 – the show is a phenomenon but it’s still on weekends on local stations, he doesn’t have a huge promotional budget. Dick Clark could have really squashed him, so that’s a very important piece that Clarence and Jesse and those folks were able to stop Clark from running Soul Train off the air. The other part is that Don never ever gave up control of the ownership. It was Don Cornelius’ show, and everything that went on that show from the scripts to who did the scramble board to how the performers performed came from Don’s eyes. That’s a very rare thing where you have a Black entrepreneur who owns and controls a property that is that legendary.

L+T: What impact did MTV and BET have on Soul Train? During that same time is when you have all of these “crossover” artists, as well, which is a point you touch on in The Hippest Trip. That seems to be a pivotal period for the show.

NG: I wasn’t surprised because by the early ‘80s, I wasn’t at home watching Soul Train as much as I used to. There’s definitely a sense that Don was aware and he began to incorporate music videos into the show because that was the hot format. There was two or three year period where he invited a lot of bands that you never thought would be on Soul Train, so clearly, he was concerned about expanding the audience. If the young Black audience was sampling this music on MTV, he wanted to be where the audience was. While Don did acquiesce to the moment and play a lot of white bands, at the same time, he still was the national place for young Black music. So when hip-hop comes in, he embraces – somewhat reluctantly – the LL Cool J’s, Public Enemy, Run DMC. And one of the things I think Don was really able to capitalize on was new jack swing. MTV wasn’t playing Guy, Keith Sweat, Al B. Sure the way that Don could. For a lot of those dancers, that was a golden era for them. New Edition was a favorite of the show, they kind of embodied old and new, they were hip-hop and R&B. The whole new jack swing era was a good time because while BET was coming up, Soul Train was still a place where a lot of these bands got their first national exposure. So while Don in the ‘80s embraced the new wave, he went back to the roots; he followed the trends and the trends led to hip-hop and new jack swing, and those were both good periods for Soul Train.

L+T: Lastly, talk about Soul Train and Don’s relationship with hip-hop, especially moving from the ‘80s into the more gangsta rap era of the ‘90s.

NG: I thought that was interesting. Even with Kurtis Blow and others, they felt like there was a certain reluctance on Don’s part to embrace hip-hop, but he did. He had the Beastie Boys and others on. But the gangsta rap thing obviously is a big turning point because while some of the earlier MC’s may have had a curse word or two, what Snoop and the West Coast people brought was a much harder edged aesthetic. The songs had to be bleeped so much on the air, so that’s a change and changes the nature of the performance. They’re not gonna be as real as what you hear on the radio. He was uncomfortable with all of that. He was uncomfortable with the attitude, the gang-banging rhetoric. It’s ironic because most of the Soul Train dancers came from the same neighborhoods as the gangsta rappers, they were from South LA, Compton, Inglewood, etc. So, the dancers were very aware of what was going on. Don worked very hard to make sure that that gang aesthetic did not appear on the show, so he had a lot of problems with it. From a business point of view, the show is not as attractive when you have to bleep out half the lyrics. From a personal point of view, he knew it was a new thing happening with young people, he knew it empowered a lot of young people, but as a soul man, he couldn’t embrace all the aesthetics of hip-hop. It was definitely a conflicted relationship.

The Hippest Trip In America: Soul Train and the Evolution of Culture and Style is available now.