Woodkid: The Creative Force For Videos from Lana Del Rey, Drake, & More Speaks on Shifting Culture

09.13.2013

MUSIC

Yoann Lemoine lives to tell tales. His stories are poetic, vivid, and layered. The singer-songwriter, video director, illustrator and animator eschews the literal in favor of the metaphorical and fantastic. His stories take shape in words on the pages of books, in drawings and animated shorts, in music videos that are more vignette than promo clip and, of course, in the verses and measures that make up his cinematic music.

Lemoine, better known to the world as Woodkid, is an auteur who has lent his directorial talents to mini-epics like Lana Del Rey’s “Blue Jeans,” Katy Perry’s “Teenage Dream,” Drake’s “Take Care,” videos among others.

Youth–or more specifically the concept of fleeting youth–is a recurring theme in his work. And the story, though veiled in metaphor, is his own: that of a boy who has made the painful transition into manhood while longing for days past. Lemoine is Frenchman of Polish-Jewish descent and he carries his people’s history with him. He is also a gay man. He is not, however, limited by those labels. They inform his identity but they don’t define him or his artistry. His art is greater than the sum of his parts.

Woodkid released his debut album The Golden Age earlier this year and Life+Times met with him in the New York offices of his record label Interscope to talk about art, identity and music.

Life+Times: Your music has been sampled by Kendrick Lamar (“The Spiteful Chant“) and you’ve done a video for Drake, how did it feel to be embraced by the hip-hop community early on?

Woodkid:First of all, hip-hop has always been a strong influence–especially for when we did the album–though it doesn’t [necessarily] sound like it. I don’t rap and it’s not really hip-hop beats or anything like that, but the aggressiveness in the production and the high-fidelity [sound] and the real clean aspect of it is what really interested us. Especially some of the patterns of drums that we translated from that [hip-hop] world to a more classical environment using [instruments] like Japanese drums.

L+T: I noticed the timing on some of the songs [on The Golden Age], made them pop accessible.

Woodkid: Yeah, yeah. Totally. On a harmonic and construction level, the album is definitely really pop. I really wanted to make songs that could be played on a guitar and a piano. But production was really a challenge for us because I wanted to bring [in] that rap culture that we have–[myself and] my producers The Shoes–but I also wanted to bring my love for cinema and [movie] soundtracks and all these crazy, massive, like pretentious sounds from science fiction movies and adventure movies. I wanted to bring that because that’s what I grew up with and that’s what made me shiver as a kid–these crazy Steven Spielberg films and Kubrick [film scores].

I think there was an attitude in the album, that was very “street” and really from that world because there was the intention of trying to break the walls and like this teenage scream … trying to be [youthful] anger. But, I’m not a rapper, I’m quite sure I wouldn’t be able to rap, but I think it works with the rap world because, of course Kendrick sampled [“Iron” for Section.80‘s “Spiteful Chant”], Juicy J and Neako sampled that song [for “Flossin'”]. I got to meet Kendrick afterwards and we’re doing projects together so it makes sense – and I’ve worked with Angel Haze. If you actually strip down my music and remove my vocals it’s very easy to rap on it–it works pretty well. I know my album is already being sampled a lot.

L+T: How did you feel when you first heard Kendrick Lamar’s song?

Woodkid: Initially, it was like “Holy shit! Are they really putting that on iTunes without asking us?” That’s the first thing. And then I was like, “OK.” Kendrick wasn’t what he is now. I had heard of him but not really. I was a little pissed to be honest, but the truth was I loved the song. Like, “shit it sounds fucking good!” So I’m not going to fucking attack him or something. Of course, my management and my label was pissed but I was more honored than anything–especially because it made sense with the culture that I have and at the end of the day it I actually ended up signing to the same label as him [Interscope]. I actually did a mash-up of [my song] “Run Boy Run,” and “Swimming Pools” together and it’s pretty amazing. I just like that connection because it is far away from who I am and very close to where I am at the same time and I think that we’re at a time where that kind of music, rap in general, is just pushing boundaries right now in music.

My audience is very, very wide, super wide. From young gay hipsters, to video game nerds, to black dudes that listen to hardcore rap and hip-hop, to 50-year-old couples that listen to classical music and I like that these bridges are being made with my music.

L+T: I see you as a person who is simply a creator. You’re a creative person and there are various outlets that you use to express yourself. So the story that you tell, and this message that you convey, can be told or conveyed in musical form, or it can be literary. I want to talk about the actual book that accompanies the deluxe version of The Golden Age. I thought it was a novel and interesting idea, tell me why you decided to do that.

Woodkid:Well, the way I built the entire project was very experimental. I’m not a musician really, I’ve been trained as a musician but I’m not like a pro, I’m not a guitar genius or a piano genius or whatever it is.

L+T: But you know how to write music.

Woodkid: I know how to write, but in a very instinctive way. I can read a score, but you can’t put the score in front of me and have me play it [immediately]. I have to rehearse … I’m a very average musician, I’d say. So what I did is I created that project in a very instinctive way. Let’s say that I have this massive table in front of me and I have all these fragments of things [on it in front of me]. Almost like archeological fragments of things I liked, things from my past, movies I’ve seen, textures of songs that I’ve heard that moved me, chord sequences [that] for some reason resonate with me–put all of these things on the table. I kept the most deep ones and black and white [visuals] started to make sense [for the project] and that kind of strong, epic “megalomaniac” sound.

I’ve been writing a lot to fragments of my stories in Poland when I was a kid, stories from the war that I inherited from my family, that was a Jewish family in eastern Europe that of course got to leave WWII and the [concentration] camps and everything, and moving from Poland to France and traveling. Germany and live during the fall of the [Berlin] Wall in Germany in 1989, all these things together were the ground for my music and what I had to say which I wanted to talk about the transition that I was living, which was the transition from childhood to adulthood. So I thought that I would put these fragments to the lyrical elements of the music, I would put the production elements, there was a whole part of the story that I couldn’t express with just the songs so I had to do videos of course, and add more fragments in the videos, it’s almost like a game, like a puzzle where there’s like traces of everything everywhere.

L+T: Adding layers to help tell the story.

Woodkid: Yeah, it’s definitely confusing and not the traditional way to tell the story, it’s not like a movie where you go from point A to point B. It’s much more fragmented, there’s much more repetition, there is parallel, there is metaphor, symbols – and the rest had to go in the book because I love writing and I’ve always been a writer.

As a director you do write a lot, it’s part of your job and I wanted to talk a little bit about Poland because it’s very blurry memories from my childhood because my dad’s French and part of my family is French. When I was a kid I would go back and forth from Poland. Technically we left when I was around six, and I only came back a few years ago when I started touring. When I came back the first time to my family’s house in the very north of Poland by the Baltic Sea, and all the memories came back intact. So I had to put that in the book but in a way that is almost like a poetic form, it’s just an essay on writing down feelings and connecting them to music and textures that I describe in my work. It is of course a lot about growing up and being gay. I’m gay and I thought it was something I had to talk about with such a personal project, but in a way there’s much more.

L+T: The boyhood to manhood theme in your music is really interesting. A lot of what you do seems to deal with the loss of innocence, why did you choose to tell that story of all stories to tell?

Woodkid: Because there’s definitely trouble inside of me that I’m trying to define. The trouble is not necessarily that I’m gay– I think it’s part of it – but I think it’s also my very strong nostalgia for my childhood and how much I love and hate my years in college… It’s a lot about trying to understand what you have to keep [from your experiences] and what you have to let go. The album doesn’t pretend to give you any answers or moral about anything, it’s just an exploration of these feelings.

It’s almost like in Africa–all the rituals that they have that transition from childhood to adulthood–are done with a sense of pain. I think it’s something that’s very interesting because it happens in such a short moment where I think in Occidental culture, it happens through so many years, that painful transition — because of society, because of everything – and it was interesting to translate that into something that was very visual that was almost this very Tarkovsky metaphor which would explain [the name Woodkid]. That would be the transition from wood [something organic and pliable], into marble–something very mineral and hard. I found out that as a gay boy it was very hard for me to keep that tenderness that I had as a kid if I wanted to grow up strong and not in the cliché of sensitivity. I had to become an adult so I had to defend myself more to the outside world because I wasn’t protected by the family and the house and the innocence that you have when you’re a kid; you don’t have to deal with paying your bills or whatever you really project on the outside.

I remember seeing videos of myself when I was young where I was obviously gay, you could tell from things that I was gay, but nobody would tell me, it was just something that nobody would really say. When I grew up I learned how to protect that, to avoid that from coming out because I wanted to be a little more inside the mold of society.

L+T: You wanted to assimilate you didn’t want to stand out for that reason.

Woodkid: I want to stand out for my art. I think that socially, there is still this very strong thing that is in the air, at least in France, I wouldn’t comment about the U.S., but in Europe being gay is not that cool. Being a woman is not that cool. Being a black person is not that cool. And though there is art is [being] made [that is] trying to defend [diversity] and promote that and try to make it not “different,” there is still something in the air that is going to be here forever because, I don’t know. Even if racism, even if homophobia is recognized as a real trauma of society that is being condemned by law and etcetera, it’s still going to be here.

L+T: Because these things have been around for so long and people have been socialized or raised to be homophobic or racist or misogynist it’ll take generations of people changing the way they think and their behavior and teaching their children to change things.

Woodkid: What I found out is, when you try not to be in a group of people–like I tried not to be into the gay community that much even though I have no problem being gay and I’ve always been out since the beginning– I found out that people define you initially by that thing. I’ve tried to get out of that because I’ve been creating and I’ve done my music and my visuals and I think that becomes the first element of my identity and that’s how people define me.

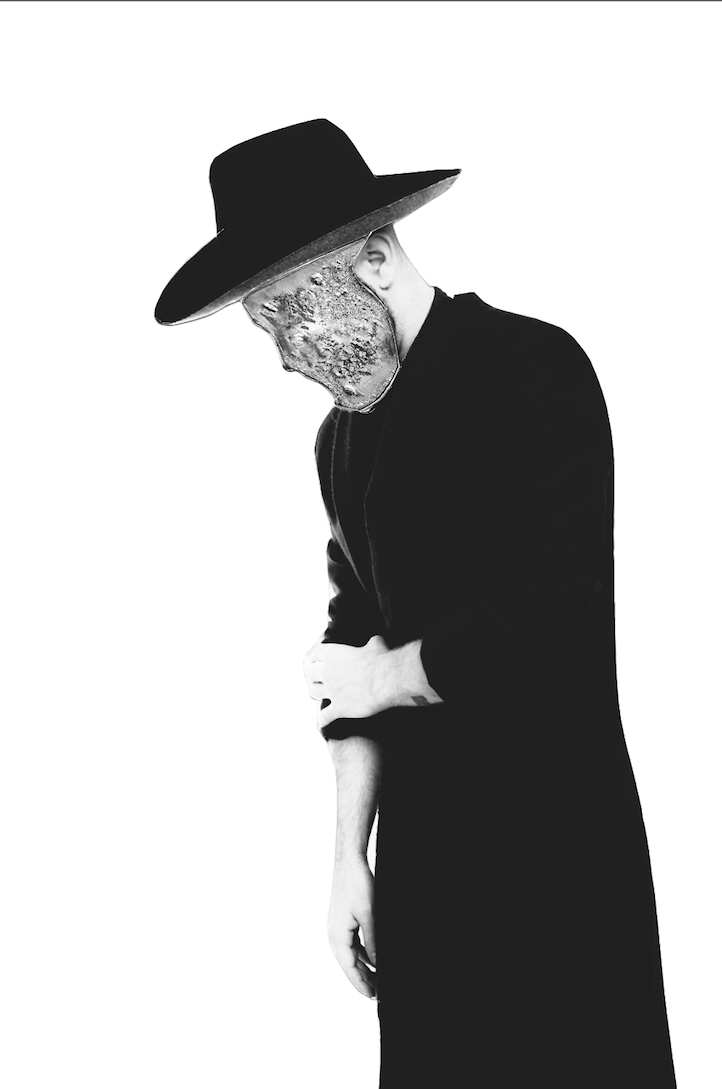

L+T: Because you’re a visual person, you pay attention to the way you look and the way you dress. Tell me about creating identity through clothing.

Woodkid: I’m not really into fashion that much but I’m very much into clothing. I’m very fascinated by the art of making clothing. First of all, because I’m really bad at it [myself] and I would never be able to do it. In general I admire artists that are able to craft things in a very beautiful way that nobody else can do. This is something that has always fascinated me, that’s why I’ve had such close connections with Kris Van Assche or people from Dior because I think they are extremely talented clothing makers. On another level I think you do create part of your identity with what you wear. You’re wearing that hat and that brand today and that tells me something about you and when you wear it you know it’s going to tell something about you. I like how clothing is something that can enhance who you are or help transform who you are because it goes into these questions about the creation of identity. I really don’t wear clothes that make me look gay and that is a question that I’m asking myself right now: Why am I wearing–let’s be a little cliché–“straight” people’s clothes?”

L+T: What do you think the way you dress says about you?

Woodkid:It depends on my mood. I actually find that depending on what I wear I will sing and act differently on stage, which is really interesting. I always wear a hat on my head because I lost my hair when I was 18, it’s always been a big complex for me–sometimes I wear the New Era hat that’s what I mainly wear the very simply one, or the “New York” one. Sometimes I wear this big kinda like Amish hats, black hats from Dior. And even if I don’t know it, somehow in my head I will act differently on stage because I know I will project something more serious or more, let’s say “street.” I have another look which is more about wearing shorts and sneakers and when I wear that I move completely differently. I know I tend to wear more things like that when I’m in festivals and I have to jump around and make people move and I know I project something much more laid back and probably more accessible than when I wear the crazy suit and the shirt and nice polished shoes–and I like that.

It’s not about being too two persons or anything like that. I have no problem with my identity, I’m one person, I’m Woodkid, I’m the same person, I just try to play different roles sometimes because it’s a nice experimentation, how your body moves depending on what you wear.

L+T: Besides clothing and of course music and and music videos what are you interested in these days?

Woodkid:What I’m interested in right now is creative directing. I’m working on John Legend a lot right now, trying to put his image together, gathering talents around him for music videos and Kanye’s [executive] producing the album so I’m trying to create that energy around the things I love because I think his music is fantastic. It’s more abstract than this I don’t pretend to just create a community of people and be the chief of anything I just think if I have that ability at some point if I have that power because of celebrity or money or whatever I’d rather use it to promote other artists rather than buy myself a villa. That’s the type of person I am.

L+T: What else do you have coming up?

Woodkid: I definitely want to do one last Woodkid video to conclude this project.

L+T: Have you chosen a song?

Woodkid: I’m not sure yet, I’m deciding between “Conquest of Spaces” and “The Golden Age.” I know exactly where I have to bring the project now; it would be more towards science fiction. I’ve creative directed the past two John Legend videos. The one directed by Paul Gore I wrote the treatment and came up with the concept because John wanted me to direct it initially but I was unavailable. I loved the track so I told him I’d help him put a team together. I did the same thing for “Made To Love” which is an amazing track produced by Kanye. I’m [also] trying to work with this girl Angel Haze more. I love her. Very few artists can sing and rap like that. She’s an amazing artist. I’m starting to write my first feature film and while I’m on tour I have time to write things so I just write ideas. I’m starting to work on a project I can’t talks too much about but it will definitely combine music and filmmaking.

L+T: Do you ever stop sometimes and ask yourself, how the hell did I end up here?

Woodkid: Yeah, oh yeah. I have moments, and I sometimes say it on stage. You have that moment where there’s a wire between the you right now and the you three years ago that connects for like two seconds, and you remember that you were just in your fucking room wearing underwear doing stuff on the computer and hanging out, doing nothing on Facebook, and you just realize the distance between these two points is so big. And for like two seconds you’re like “What the fuck am I doing here? Is this some kind of joke? Is it going to go away or is that some reality show called ‘People Pretending To Be Famous?’ It’s very, very strange. I think it’s important to keep that [humility] too, as Jennifer Lopez says: “I’m still Jenny from the block.” [Laughs]