Visual Artist Jennifer Rubell Discusses “Free” and Future Projects

03.13.2013

ART & DESIGN

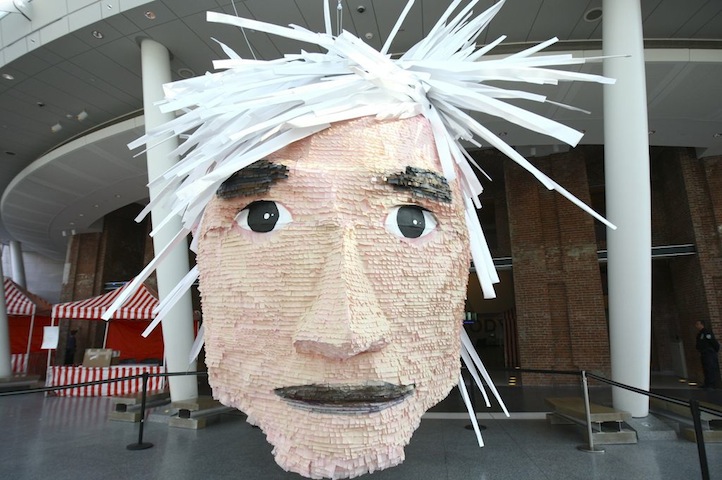

Jennifer Rubell has sworn off food, at least for now. The New York based artist has worked with food as a medium in grandiose proportions in many of her projects — 1,521 doughnuts, one ton of honey-dripped ribs and an entire cell padded in pink cotton candy. Rubell’s most recent installation is “Free” at the SCAD Museum of Art in which the edible object of attention is what she describes as the “lowly buttermilk biscuit.” Her installations have been exhibited at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum and at the Saatchi Gallery in London. Rubell worked as a food writer before pursuing an art career. She has a B.A. from Harvard University in Fine Arts and attended the Culinary Institute of America. She is the daughter of art collectors Don and Mera Rubell and for ten years she hosted a breakfast project at the Rubell Family Collection featuring her edible work during Miami Art Basel. Rubell’s other recent work includes a wax statue of Prince William bearing a ring. She says “Free” is her last project where food will be her medium.

To experience “Free,” visitors enter a dark forty-foot long chamber encased in a dark gallery, and when their eyes adjust to the dim light they may reach for a buttermilk biscuit. They may kneel on a cushion before an altar and behold a steady drizzle of honey flickering in lines of light. Some visitors dip their biscuit in the beckoning honey and nibble at the sweet and savory food. When they emerge from the quiet container, the light is jarring. A smattering of crumbs trails outside of the museum as evidence of the audience participation. However, other visitors exit quickly, taken aback by the element of participation in the work and the boundaries it crosses, making the spectator a conscious participant in the experience of the work. This relationship is at the heart of Rubell’s work, which is constantly examining the mores of the art world. Life + Times spoke with Rubell in Savannah about the making of “Free” and her evolving subject matters.

Life+Times: I understand you worked with local Georgia groups to put the exhibition together?

JR: It was inspired by this place called the United House of Prayer for All People. They run a restaurant and the proceeds from the restaurant fund the church. I love the idea of the food being the economic means to a spiritual undertaking. They make their own buttermilk biscuits for their congregants that they won’t sell. The actual biscuits come from this place called Starfish Café, which is a homeless training program that trains people in culinary arts. I love that the lowly buttermilk biscuit can hold those various positions. Since SCAD is a museum that’s part of school, it will certainly be seen by a lot of students. I very much wanted to explore the transcendent moment in art, which is kind of like the only reason to interact with art to begin with. You go into this very dark humble chapel structure and figure out how you’re supposed to interact in it. Then you’re supposed to violate the entire viewer art contract. You touch everything, you taste it, eat it. You’re doing everything one shouldn’t do in a museum context. It’s in this light locked gallery and when you come back into the museum it’s like the light is so bright it’s blinding.

L+T: So it toys with the notion of sin.

JR: It uses religion purely as a referent about meaning or as a parallel to art, but its no commentary on religion. The religious language, especially in relationship to food can be a language of transcendence.

L+T: You are known for doing incredible work with food.

JR: I’m actually moving more away from food. It’s the most difficult medium. It’s very, very challenging and it’s fundamentally ephemeral. I’m very interested in durability. You’re dealing with a lot of readymade qualities. I’ve been using it to address the things that’s are of interest to me, which mostly have to do with standardized rules inside of art and the art world and examining those and subverting them and transgressing the boundaries.

L+T: Do you feel like this will be your last work using food?

JR: Yes, but I say that and I do it again. I constantly say it’s my last piece using food. Everything that I’m working on in the studio now deals a lot with interactivity, but not food. However, for me the way that I use it food is such a powerful medium to that I’m sympathetic for my own inability to kick it as a medium. I kind of take pity on myself. Food for whatever reason has become our culture’s location for a lot of different conversation. In the ‘70s that was sex. Sex was the place you got into social inequality and conformity and non-conformity and now I think food really occupies that realm. It serves a lot of the same function – pleasure and that there’s some morality attached to that pleasure.

L+T: What’s the shift moving toward that you’re working on now?

JR: It really started with my engagement project – the wax sculpture of Prince William with the ring on his sleeve. People would step up and slip their fingers into his ring. It deals with the idea of the art object that offers the viewer the opportunity to become a part of the visual language of the piece, to become a part of the subject matter. I’m also working on a painting project, which is really exciting to me. To me that work is familiar to the food work. It’s extremely connected.