The Commission

01.04.2012

LEISURE

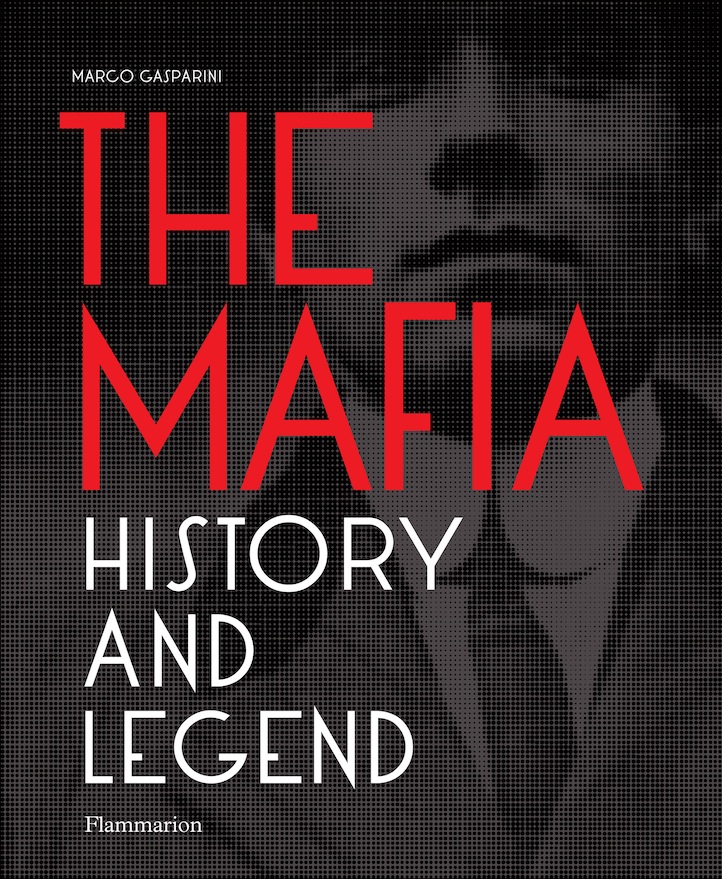

Did the Mafia play a roll in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy? The book The Mafia: History and Legend, by Italian financial journalist Marco Gasparini and translated by Brian Eskenazi, explores the fine line between mythology and known fact about the Mafia’s history and methods. Gasparini’s coffee table book is a primer of the underworld inhabited by the Sicilian Mafia and the American Cosa Nostra, using both text and visuals to convey the emergence of the powerful organized crime operation.

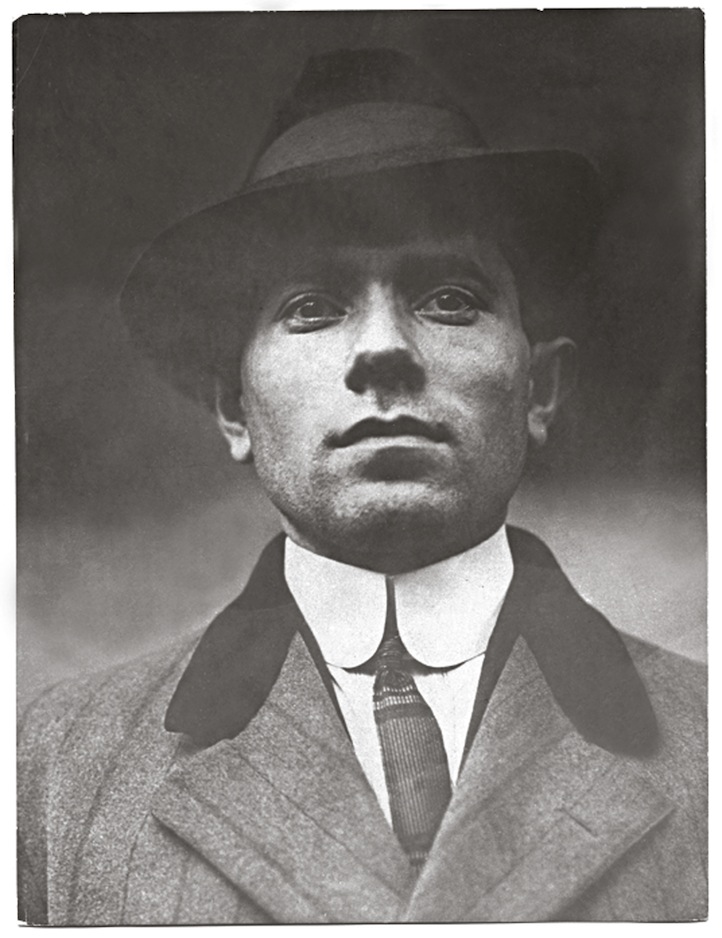

Readers in pursuit of gangster trivia will relish in details, such as how the Mafia communicate using pizzini — tiny scraps of paper filled with secret codes. Infamous gangsters Al Capone and Lucky Luciano play a prominent roll in the book for their notorious reigns. Gasparini researched the nature of the Costa Nostra criminal practices, and explains how murdered victims vanished using lupara, a term that translates to “white shotgun.” Then there are the ruthless killings and kidnappings. “In an attempt to discredit the evidence against it before its ultimate defeat, Murder, Inc. contrived a strategy reminiscent of Hamlet in which the king is killed by poison poured in his ear,” Gasparini writes. “The victim was to be killed by an ice pick stuck deep inside the brain through the auditory canal, to lead the coroner to conclude that death was from a hemorrhage. It was a crude but effective strategy that seems to have been used even by a boss as high up as Lucky Luciano.”

Gasparini takes well-known Mafia tactics and traces how these practices started, including the steady clap of gunfire. ”“The staccato rhythm of a machine gun accompanied a Mafia crime for the first time in Sicily on August 27, 1946, having arrived three years earlier with the Allied landings. Two brothers, victims of a vendetta, surprised while playing cards in front of their house in the neighborhood of Ciaculli in Palermo, fell under a burst of fire, that killed one of them.”

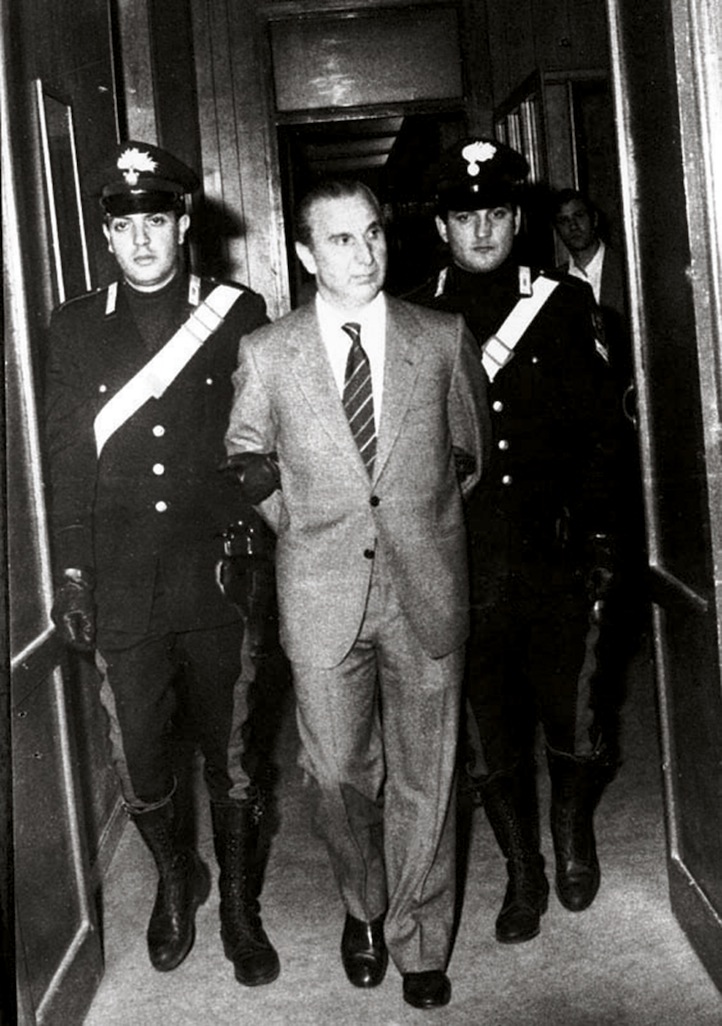

The author addresses one area that not much has been written about — the roll of women in the Mafia, as participators and foils. Gasparini also reveals information about tipoff that shed light on the structure of the Mafia and the overseeing Commission made of representatives of the various neighboring Mafia clans. “At the head of the Commission was the Padrino dei padrini, or “godfather of godfathers.” He in turn was in contact with people at higher levels who operated in secret and were in collusion with still others at the very highest level of government,” one passage reads.

Gasparini’s background in financial writing is apparent in the chapters that break down Mafia economics, including arms trafficking, prostitution, public contracts to the illegal disposal of waste and the spread of white-collar Mafia investments. He touches on international organized crime including the Japanese Yakuza and the Russian and Chinese Mafias. The book ends on a mythological note, summarizing the Mafia’s rise to fame in cinema from the original 1931 Scarface to The Godfather trilogy.