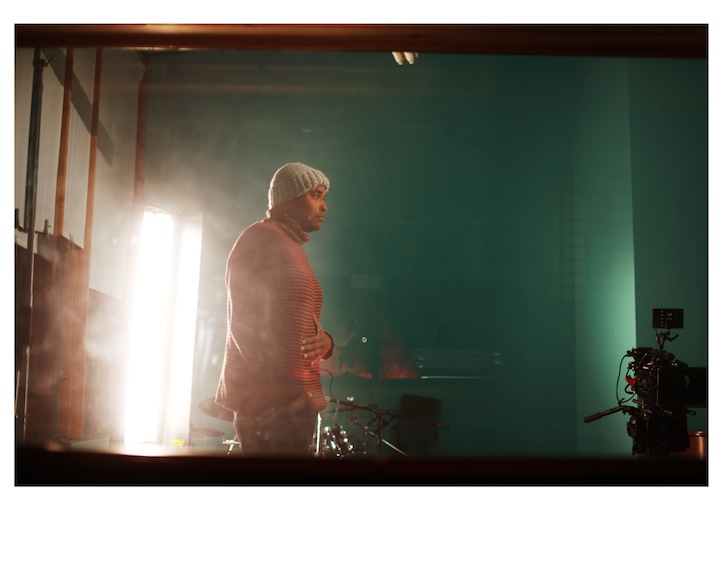

Respect the Shooter: Shawn Peters

07.02.2012

ART & DESIGN

Unless you’ve been deeply involved in the contemporary New York art and music scene, you might not have heard of Shawn Peters. Personal modesty and a deep abiding desire to remain behind the scenes where his eyes sculpt new visuals for the avant-garde has kept Peters off the public radar. Yet, his meteoric rise behind the camera will not allow him to remain in obscurity for long. The Brooklyn based, New Rochelle raised Peters has been quietly making his mark behind the lens for artists as varied as Blitz the Ambassador, Pharoahe Monch and Gregory Porter. Peters, along with visual alchemist Terence Nance recently completed Triptych for Afropunk Films–a new series of documentary shorts that profile the work of artists Sanford Biggers, Wangechi Mutu, and Barron Claiborne with others to follow. Triptych debuted at the Brooklyn Museum on May 24th. Peters and Nance also collaborated on An Oversimplification of Her Beauty which went to Sundance and Blitz the Ambassador’s short film Native Sun, shot on location in Ghana. Peters also serves as the consulting Performance Producer for the Weeksville Heritage Center in Brooklyn and has been instrumental in featuring artists such as Meshell Ndegeocello, Jose James, Pharoahe Monch, Cody ChesnuTT, and Theophilus London.

In Peter’s words he is “just getting started” and like most, his journey to finding his creative genius has been far from a straight line. We recently caught up with him between shoots to find out what that journey has been like and who and what has inspired him to devote his life to the world of film and the creative imagination.

Life+Times: When we talked a while back you mentioned that one of your greatest influences was famed Harlem photographer Roy DeCarava. How has DeCarava’s work shaped your approach to image making?

Shawn Peters: When I was in graduate school at the University of South Carolina I was in the media and film program with a concentration in cinematography but I shifted half way through to still photography. My professor and advisor Gene Crediford was an older white guy who was from the South and he really mentored me. He and I became very close and he would always tell me that I needed to check out this guy Roy DeCarava. This was in the mid-90s and I had never heard of Roy DeCarava back then because most of us had only heard of James Van Der Zee, Gordon Parks and others. DeCarava was not part of the mainstream discussion when it came to black photographers—at least in my circles at the time. My professor, however, insisted that I learn about his work so after I graduated I moved back to New York and I sought him out. I learned that he was teaching at Hunter College so I called his office multiple times and finally got him on the phone. After a short discussion he agreed to take a look at my portfolio and he spent at least a half a day with me examining my images and offering critiques of each one. He told me about some of his dark room techniques in terms of printing and took a lot of time with me that day—something he did not have to do. I didn’t spend that much more time with him after that, but I later ran into him at The Museum of Modern Art during a huge retrospective of his work. So DeCarava has been a huge influence on my image making because his work was never commercial—it was very quite and he had a very personalized approach to seeing light and how it interacted with form and subject. So I try to approach my work as he did.

L+T: Your work today is primarily concerned with cinematography and you have returned to where you began in graduate school. Why the return and what has that transition been like?

Shawn Peters: Well after graduate school in 1995 I was broke. I was interning on film sets and working to get photography jobs but I was not making it. So I made a choice to get a job and I ended up working for AT&T for about four years and did very well. I was later asked to be a partner in an IT firm with some cats who had retired from AT&T and that lasted an additional four years. I was making great money, but I was not happy. So I got into the music business because I figured that would put me in touch with the arts so I started working with Martin Luther, Cody ChestnuTT, and I helped to found Rebel Soul Records. I ended up spending another three or four years doing that. Finally I decided to return and do what I always wanted to do so I enrolled into New York University’s Summer Intensive Cinematography program in an effort to get updated on the new technology and get back in the fold of filmmaking. Just as I got back into it DSLR film technology took off and high quality filmmaking became accessible and affordable to anyone. Shortly after I finished the program I went out and bought a Canon 7D and after having it for two days I was offered an opportunity to be the director of photography for Blitz the Ambassador’s video “Something To Believe.”

Native Sun • A short film by Blitz the Ambassador & Terence Nance from MVMT on Vimeo.

L+T: You seem to have remained quite busy since the NYU course and have been working with people like Pharoahe Monch and jazz vocalist sensation Gregory Porter.

Shawn Peters: Well after working with Blitz things just snowballed from there and I began being contacted by folks in the music industry who were coming to find out that I was now behind the camera following my dream. Monch liked the “Something To Believe” video and his management got in touch and we met at my apartment, clicked and agreed to make Pharoahe’s “Clap” video.

L+T: In your most recent work you have been working a lot with director Terence Nance. How did that relationship develop?

Shawn Peters: Well let me go back a bit. Actually the first film I ever served as director of photography (DP) after NYU was in Holland. I was not using a DSLR, but a Sony E-1 with a 35mm adapter. We shot the video for a song called “The Way” for a Dutch artist named Postman.Well one day I saw a fundraiser campaign on the Internet for a film by Terence Nance and I was really impressed with his creative approach and aesthetic choices. I thought to myself wow I would really like to meet that dude. So after not really thinking about it again I get on the train near my home in Brooklyn and I randomly run into him. Terence has that big hair so you cannot miss him. So we started rapping and it turned out that we had a mutual friend in Blitz The Ambassador. I told him that I was a DP and he asked me to send over my stuff because he was looking for a DP for Blitz’s “Something To Believe” video. So I sent him “The Way.” He liked it and hired me for the job days after I had purchased the Canon 7D. This then led to me bringing Terence on board for the “Clap” video for Monch. Now interestingly, Terence almost did not make it on the video because Pharoahe’s people thought his ideas were kind of out there so I conceived the original outline for the film. I later hired writer Kevin Nelson to write the screenplay and then Terence re-wrote the script to his style and adjusted things to his directorial vision and then we shot it. “Clap” put us on the map and was one of our better pieces in my opinion.

L+T: Now you have been doing a lot of work with Gregory Porter. What has it been like to be part of his meteoric rise on the music scene over the last two years or so?

Shawn Peters: Well what’s interesting is that I know Gregory from around the way in Bedstuy. Gregory’s brother had a coffee shop in the neighborhood called BreadStuy and Greg used to make soup and hummus and fancied himself as a chef who could also really sing. Every now and then Greg would have gigs in some of the local spots around the way. So fast-forward…my aunt, who is also my spiritual advisor has a spiritual center up in New Rochelle where I grew up. Well she always encouraged us to bring folks up to perform at her center so one day I brought Greg up there and he just blew the whole place down. My clairvoyant aunt stepped to me and was like “Listen this guy is going to do it—just watch him in the next couple of years because he is going to take off.” For obvious reasons I never doubted my aunt’s ability to see the future. After Greg dropped his first album I was asked to DP the video for “Illusion.” Greg’s brother Roy was supposed to direct it but for all kinds of reasons he was overcommitted in other areas and was unable to do it. I ended up directing and shooting the video myself. That was the first time I directed. After that they brought me on to direct the “1960 What?” video out in Detroit. I later ended up collaborating with director Pierre Bennu, someone I had known for years, on Greg’s “Be Good” video.

L+T: Well you just celebrated your 20 year college reunion from Morehouse College and its amazing that you went to school with some major players in the art world today. You were fortunate to count folks like folks like Saul Williams, Martin Luther, Sanford Biggers, Corey Smyth, Tahir Hemphill, Adisa Iwa, and DJ Soul Messiah just to name a few as your classmates. What was that experience like?

Shawn Peters: Well what’s interesting is that Morehouse is not known as a school that focused a great deal on the creative arts, but many of us pursued art because of our tremendous desire to offer something artistically meaningful to the world that was particularly relevant to reclaiming our dignity as a people. I mean Saul Williams was a philosophy and theatre major and his efforts in those arenas shaped his poetry and music prowess. Martin Luther majored in mass communication and was a filmmaker in college. The great thing about Morehouse was that we all learned about the importance of articulating ourselves, whether it was behind the camera, on the stage, in the pulpit, or in front of the classroom. I mean Sanford Biggers work focuses primarily on cultural identity and ‘reriteing’ history through art—that is seeing history itself as a malleable art form. Recognizing that history is written out of a creative selection of ‘facts,’ Biggers’ work seeks to treat history like sculpture with an eye toward remolding the past. So in essence, all of us share a common interest in using our voice to advance the collective interests of our people and humanity in some kind of way. Morehouse taught us that and I am forever grateful.

Photo Credit: Marvin Joseph