Kingdom Come

08.17.2011

ART & DESIGN

On September 23, 2011, The Brooklyn Museum mounts a ten-year survey of thirteen works by the artist Sanford Biggers. The collection of work dubbed is “SweetFunk–An Introspective.” A native of Los Angeles, where he grew up in Baldwin Hills, (a professional middle class enclave that sits above South Central), Biggers has lived a life that refuses binary definitions. He plays piano, practices Buddhism, has traveled the world and taught at Duke and Harvard University (and is currently at Columbia University). He’s done installation in glass, metal, rice and sand and multimedia pieces where he directed actors in short films and produced a minstrel show in Manhattan’s theatre club The Box. As a child of the 70’s and later the hip-hop generation, Biggers’ attention to Black male bodies in spaces, be they on dark city streets, or bright Japanese bamboo forests, are informed by both resistance and entitlement. The centerpiece of the “SweetFunk”, “Blossom” looks at the way a black teenager exercising, then defending his sitting under a tree continues a conversation from the early twentieth century.

Life+Times: Name a single piece of art that you return to for inspiration.

Sanford Biggers: A large installation I saw by Willie Cole in 1998 Museum of contemporary art in chicago it was a huge installation of about 40 doors he’d salvaged from homes in the hood that were in disrepair and were going to be torn down and he’d take four doors and make them into crosses standing upright and he’d made about 10 of them and you could walk through them like turnstiles and he had lawn jockeys painted different colors that were stand ins for Elegba, the gatekeeper in Ifa religion and those door became symbols of the crossroads. I don’t know if it influenced me but it affected me. It spoke to things I was curious about and encouraged me to think about things I wasn’t thinking about.

L+T: You play; Who’s your favorite pianist?

SB: Erroll Garner, Thelonious Monk and Herbie Hancock…and my favorite body of music are the records Miles’s made with his second great quintet with Tony Williams, Ron Carter and Herbie Hancock.

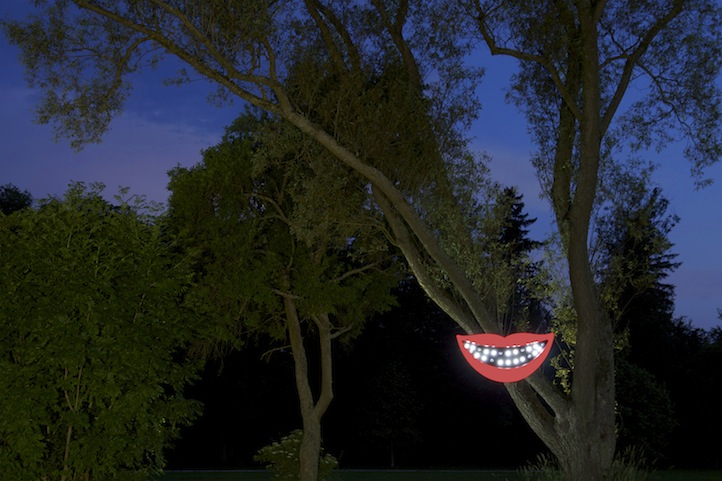

L+T: You’ve got that massive billboard painting up currently, the “Chesire.” How did growing up in L.A., a town that gets called artistically vapid, often, affect you as a growing artist?

SB: I grew up in a black neighborhood, Crenshaw and Slauson, and the kind of artwork that’d I’d see in my parents and their friends houses were prints of Elizabeth Catlett and Charley Wyatt occasionally John Biggers. I carpooled to a white school and in their homes I’d hear ska and ironically reggae. By the time I got to high school I was doing grafitti with Korean and Mexican kids and my high school was very diverse so it opened me up culturally which later inspired me to travel around the world which of course influenced my work.

L+T: I’m going to name a few of your piece and I’d like you to comment on your thinking when you created them. I’ll begin with “Lotus,” mounted on the outer wall of the Bronx Eagle Academy.

SB: The Lotus is the Buddhist symbol for harmony and perfection and it grows out of the muck and mud and blossoms at the top of the water in all its beauty. With my sculpture, which I did originally in glass and we mounted on the school in metal, each of those petals is a bisected slave ship filled with human cargo. According to the diagram they packed about 370 Africans into the hold of the ship. My petals total represent 6,000 Africans being transported by slave ships. I mounted this piece on the Eagle Academy for Men, where mostly Black and Latino teenage boys attend. Of course it symbolizes our common history in Africa, but from far away it seems a beautiful flower and the closer you get you realize exactly what it is. I was hoping that through meditating on this image, they could focus not only on the pathology of slavery but our miraculous ability to transcend slavery.

Ghetto Bird Tunic

That piece is inspired by me growing up in Los Angeles. I was visiting home about 15 years ago and me and a friend parked on a hill overlooking the city and we could see seven or eight helicopters dedicated to the aerial patrol of specific neighborhoods. They’d hover back and forth in patterns. Of course the slang in the hood for these helicopters is ‘ghetto bird’. I was later asked to do a project for Princeton’s University’s Art museum and I wanted to riff on some of the other african pieces in the collection. Being on the east coast and living in Harlem you see brothers wearing these huge bubble jackets made with goose feathers to keep warm. So for the Ghetto Bird Tunic I put the feathers on the outside and next to the coat in the museum I placed text explaining that this could be used as a rites of passage costume for any young black male living in the U.S.. The idea being that you put on the coat and go outside at night when the ghetto bird is out the tunic will serve as a camouflage to protect you from being detected the aerial hunters (cops) and you’ll survive the cops to manhood. I made them in three sizes: a full length for adult men, a mid length for teenagers and a tiny one for toddlers, because you can never start running from the cops too soon.

Blossom

Blossom is a sculpture I did of a baby grand piano with a fabricated tree coming out it, or the piano coming out of the tree depending on how you perceive the piece. It was inspired by the 2006 Jena 6 incident in Louisiana. That incident began because a black high school student sat under a tree white students had claimed and the next day when he came to school there were nooses hanging from the tree. At the same time, the Buddha found enlightenment sitting under a tree. So I was thinking about the tree as its own mixed metaphor. Then I programmed the piece to play Billie Holiday’s song about lynching “Strange Fruit.”

L+T: What are your regenerative rituals?

SB: I meditate, I do yoga. And I look at mediation and yoga as my way of praying.