Reclining Nude

12.22.2011

ART & DESIGN

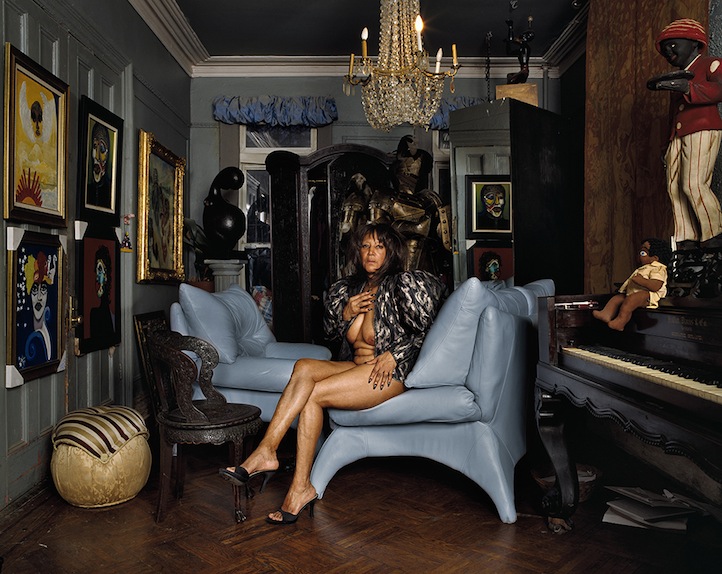

The standout star of New York’s Museum of Modern Art’s 2011 “New Photography Series” was Deana Lawson. An upstate New York native who’s been nesting in Brooklyn with her painter husband since they both graduated from the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, Lawson is re-imagining the portrait in wildly subversive ways. Nudity and power are central to much of her work, which is often staged in domestic spaces – living rooms and parlors, or bedrooms flooded with artificial light. She manages to turn a family portrait into a visual essay on love and power with a shockingly casual, carefully posed, nude mother. Curator and critic Franklin Sirmans, who was an early advocate of Lawson’s work, has likened her to Black women photographers like Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson and also to Nan Golden and Diane Arbus. Sirmans has written that Lawson’s work is “packed with intention.” Indeed, Lawson spends her time alternately daydreaming about the images she’d like to produce and considering their theoretical implications. Here we discuss gaze, talking women from the A train into posing nude, and success.

Life+Times: Your work has been compared to Diane Arbus and Nan Goldin, but so much of what you do to deconstruct boundaries reminds me too of Jacob Holdt, except you’re hardly passive. You seem to direct your models poses, down to the inch, sometimes placing them in fairly unnatural, uncomfortable spaces. How much of your portraits are staged in your head before the shoot?

Deana Lawson: I often photograph in the subjects’ home, or what a good friend of mine has emphasized as a dwelling. The “home” or the apartment becomes a heightened space where the subject and myself engage in making the picture in relative privacy. In that sense the space feels to us completely natural and comfortable for the occasion of making a nude portrait. I think the “unnaturalness” or “uncomfortableness” that you mentioned might have to do more with looking at these sorts of pictures which feel very private, in a public space. Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, Jacob Holdt and myself share an affinity for the photograph as document and testimony. Yet formally my work is far more staged and I tend to work in a more painterly way, carefully considering lighting, poses, and environment. I daydream a lot – more than I like to admit – and when an image comes to me, I try to make the picture as close as possible to the dream. But other times, I revert to documentary mode, as in the picture Flex (below), I could have never imagined a picture that profound. So I have a hybrid method of working where many images might be preconceived, but others influenced completely by meeting powerful subjects.

L+T: Your nudes, no matter how seemingly random, never seem overly vulnerable, or even performative. Clearly you’re thinking about women stripped of clothing in these domestic spaces. Can you share some of that thinking?

DL: I’m thinking of all kinds of nudes: keepsake nudes, King Magazine semi-nudes, vintage flea market nudes, clinical nudes, stuffed-in-a-drawer nudes, pornographic nudes, ethnographic nudes, …simultaneously, I’m also thinking of portraits, family album and studio portraits. I was fascinated by portraits before I was interested in nudes. Thus I always imagined I was making portrait even though I was beginning with the constructs of a nude.

L+T: So much of feminist theory as it relates to images centers around the gaze. I’m certain you’ve studied Laura Mulvey and the like, but when you’re posing your models, are you considering issues of power and hierarchy?

DL: To meditate on the “gaze,” there are three at play: the subject’s gaze, my own gaze as photographer, and then the gaze of the audience. All are essential for the picture to become most charged. Each gaze has its own legacy of power or powerlessness. And thus a dynamic energy is exchanged between gazes, between self and other. I can’t think of a better example of my power politics illustrated so clearly than in the image Baby Sleep (pictured, top). In this photograph, there are three people in the room, and only one person gives you a clear and direct gaze, and that is the wife/mother/succubus figure. She plays several roles at once, and very gracefully. Her role and position of power as wife, lover, and mother, is honored in this photograph, and she is very much aware of being looked at, by me, and by you.

L+T: You’ve talked about wanting to center your work around ordinary women, women you meet in the street or at church? How exactly does one talk an average woman into a state of undress? Do you mostly get your way?

DL: I am drawn to seemingly ordinary women, and what I mean is I’m not interested in the super-star en vogue sort of beauty. We see enough of that. I’m attracted to the everyday person who I might run into getting off the A train, or whom I might pass in Foodtown. This is the person, the woman, who I want to use as my muse. And the subject is not average, in fact, I believe the subject is extraordinary. I do not always get my way, 87% of my process involves failure and frustration. All I can do is present my idea to the subject and hope they are creative and open enough to just maybe… say…yes.

L+T: Your husband, Aaron Gilbert, is a really talented painter. You met while you were both studying at RISD. Do you discuss and/or collaborate on work at home?

DL: We met before RISD. We met in Happy Valley, the town of Penn State University. When we first met, Aaron had a room in a big house that he shared with four other young guys. After class I would race to his house and run upstairs to his room, which was our experimental space. And we would just make stuff, we made sculptures, I would pose for his early paintings, I would make Polaroids and so forth. That time was an incubator period for our careers and our relationship. When I was around Aaron, I felt I was in the presence of a true artist. His focus was razor sharp, this man could paint to 3 a.m., and I had never experienced that sort of discipline before. In our recent work, Aaron makes pre-sketches for many of my portraits and I am often the main character in his paintings. So our relationship always involved an element of collaboration.

L+T: Your recent exhibit at MoMA was incredibly well received. It has to be satisfying. What’s your relationship to success? Do you allow yourself to enjoy big and well-reviewed shows? Or do you push yourself towards the next project?

DL: When I first found out MoMA chose my work, of all the photographers working out there right now I felt like it was a huge success, not only for me, but for the subjects in my work. It was also a little scary, because an institution of that magnitude opens up your audience to hundreds of thousands of people and gazes. With that said, I get antsy and irritable when I’m not creating new work, so I’m always pushing towards the next project…