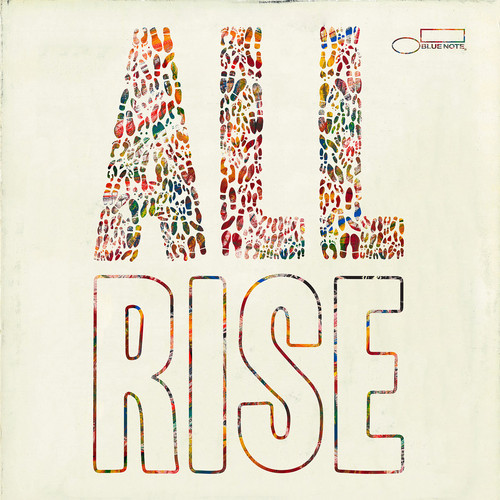

Jason Moran Discusses New Album “All Rise: A Joyful Elegy For Fats Waller”

09.18.2014

MUSIC

For three years, pianist Jason Moran and R&B crooner Meshell Ndegeocello have been in Harlem telling the story of legendary jazzman Fats Waller while performing at the Harlem Stage Gatehouse. With their new album All Rise: A Joyful Elegy For Fats Waller, they now present his tale to the masses, building on their live show and putting it on record.

Taking Wallers’ music and reshaping it for a modern audience, the emphasis was on dancing. Hence the name, All Rise. Moran, Ndegeocello and company do a strong job getting this point across while still maintaining the integrity of the original works. Life+Times talked with Moran about All Rise, re-creating Wallers’ music, working with Ndegeocello and more.

Life+Times: Go back to 2011 when you all first started with the stage show.

Jason Moran: Any time I’m presented with a commission, then the thought is, “How do I exceed not only my own expectations, but also the expectations that the presenter and everybody around me has?” That’s the challenge I always pose to myself. When the Harlem Stage [Gatehouse] asked me to consider playing Fats Waller’s music – I love Fats because of what he means to American history, especially American music history – I knew his prominence as an insanely famous musician in the 1930’s and 1940’s could only resonate so far in 2011. It was to reconnect with what Harlem had and its dance music history, that was an aspect that I was going to try to investigate. Just like hip-hop used to be dance music and it no longer is, jazz music has kind of gone through the same evolution. It’s a thing that watch with bated breath, how jazz will continue to change. I thought that after all these years that I’ve been a jazz musician, I’ve never played for a dancing audience, and this was a time to try to address it and Fats Waller’s music was a great vehicle for it.

L+T: Was Meshell a part of that show with you?

JM: Yeah. The other part about it is I don’t sing. Fats Waller is all about this technical mastery at the piano, but he’s also about this extreme wit and a great casual voice when he sings, and I needed someone that could function as that. A couple years before this moment, I met Meshell and we talked about wanting to do something together, and I thought this would be a great opportunity because of how she manipulates a crowd, a song, she has one of the most distinct signing voices out here, she’s a great arranger. She was my partner in making this and looking at the music critically trying to find some of the spaces the songs could function in. She was a big part of developing a lot of the songs.

L+T: How was the dancing response to live show from the audience?

JM: Well, you know, people like to dance late at night [laughs]. People who showed up to the 9 o’clock set were cool, but the people who showed up to the 11 o’clock set were ready. In the jazz world and the classical concert world all across the globe, concerts generally start at 8 o’clock so that gives you a certain kind of audience. For these performances – and we’ve done them consistently for the past three or four years – the later it is, the better. The more loose the audience is when they arrive at the space, the better it is. The closer they are to the stage and the more space they have to get down, the better. It’s difficult to make people dance [laughs], and sometimes we succeed, sometimes we don’t. We also try to make the music interesting if you just sit down and listen to it too. That’s what Fats Waller was able to do. I never went to a Fats Waller dance party, but I sure have listened to the music enough to know that even without me standing up and dancing, it’s still a lot to digest sonically.

L+T: Did you know you would make it into an album when the show started? How did making the songs in the studio change the way they were played?

JM: The good part about having three years to develop music is that it just continues to evolve every time you perform it. When we first started it, I didn’t consider making a studio record of this because I’ve been into, recently, just making pieces people experience live. There is no duplication unless you’re sitting in the seat. That’s how most of my commissions just sit in front of audiences, they don’t get recorded onto DVD for visual sake or onto audio. To make it in the studio, instead of having them be long and letting people get into the groove, we shortened them and truncated everything. Also, what I found we needed was somebody who understood sound as much as I understood how to play the piano. That third element was the engineer Bob Power. He’s a legend, from D’Angelo to A Tribe Called Quest to Common, he’s engineered a ton of great records. Meshell has worked with him a lot and Bob, I think, really got the songs to feel juicy. A jazz engineer, they do different things. But I was looking for something juicy, and Bob was able to help lure that out of the songs and help me edit the songs together, and Meshell has really strong ideas about order. So, all of those things helped.

L+T: Meshell has done R&B and hip-hop, and Bob Power has, too. [Drummer] Charles Haynes has worked with all kinds of artists, including hip-hop. Expand on the idea of making it more “juicy.” How did you take the music and modernize it for 2014?

JM: Some of those songs, even slow songs, say “Jitterbug Waltz,” if you listen to Fats Waller’s original version, this is drastically different from that. Saying the word “waltz” means the song is gonna be in 3/4 [time], so we made this like a slow Isley Brothers or something. For us to look at dancing is for us to look at intimacy, relationships and what those moments mean when you’re close together. What we can get from playing live is something different, but in the studio you try to sculpt the sound in a way to make a person feel like they need another person to listen to this song with. Listening to it alone is fine, but you wanna find someone else to be with on certain songs. If I put on Voodoo, it’s like, “Ok, where’s my wife.” Certain records make you do that, so that’s what we’re going for. Meshell takes apart the song “Ain’t Nobody’s Business” and slows it way down, and we get into almost like a psychotherapy version of what Fats Waller may have been thinking. Here’s a man who died when he was 39 years old, he went through a lot: his father was a preacher, he liked to drink a lot, he clearly liked women a lot. So, when we make this record, we’re trying to tell this story through a critical lens as well, like Good Kid, Maad City totally changed the narrative of how to talk about the hood. Hopefully people will follow that thread because there’s a lot more to critique than just the simple things we’ve heard for decades. [Kendrick Lamar] changed that language, so we’re trying to change the language of how – this is 80, 90 years ago – that music sounds. In jazz, we play until we die. So for Fats Waller, I wanted to leave his music open to that kind of discussion. We all know from comedians we’ve followed, whether it’s Dave Chappelle, Richard Pryor, Lenny Bruce, these people are also tortured, too. A person like Fats Waller who has so much effortless joy and easy candor, that’s draining as a performer. This music looks at that conversation, too. People may or may not hear it, but it was definitely part of how sculpted the conversation around Fats Waller.

L+T: Over the three years, have you developed a favorite song to perform or a song that you dig the way you all flipped it?

JM: The biggest one could be “The Joint Is Jumpin’.” It’s also the third track on there which is “Yacht Club Sing.” Those things get my blood boiling and when we play them live, it gets people ready. Those songs are tempting in a lot of ways and when they go right and we hit the right frequency, it can really drive a crowd crazy.

L+T: Talk about wearing the Fats Waller mask.

JM: In developing this project, I’m looking for layers of meaning, meaning I’m not just going to play the music and that’s it. That’s not interesting enough for me. Visually, I had run across this place where you can buy a mask of Ronald Reagan, George Bush, Barack Obama, Spiderman, all these great figures or mythical figures, but there are no jazz masks. Fats Waller is just [as much] a mythical and great figure for American history. I found this artist Didier Civil. He lived in New York and he worked out of Haiti, and I sent him some photos and said, “Yo, can you make this mask in a couple of weeks, I need it for a show?” So I commissioned him to make a couple masks for me. A lot happens when you put on a mask. You shield yourself from your audience, but you’re in someone else’s face. When I first started, I didn’t wear it that much, but now I’ll wear it for more than half of the show. It’s this weird trip being inside his head, but it’s also this resurrecting of him and his spirit, too.

All Rise: A Joyful Elegy To Fats Waller is available here.