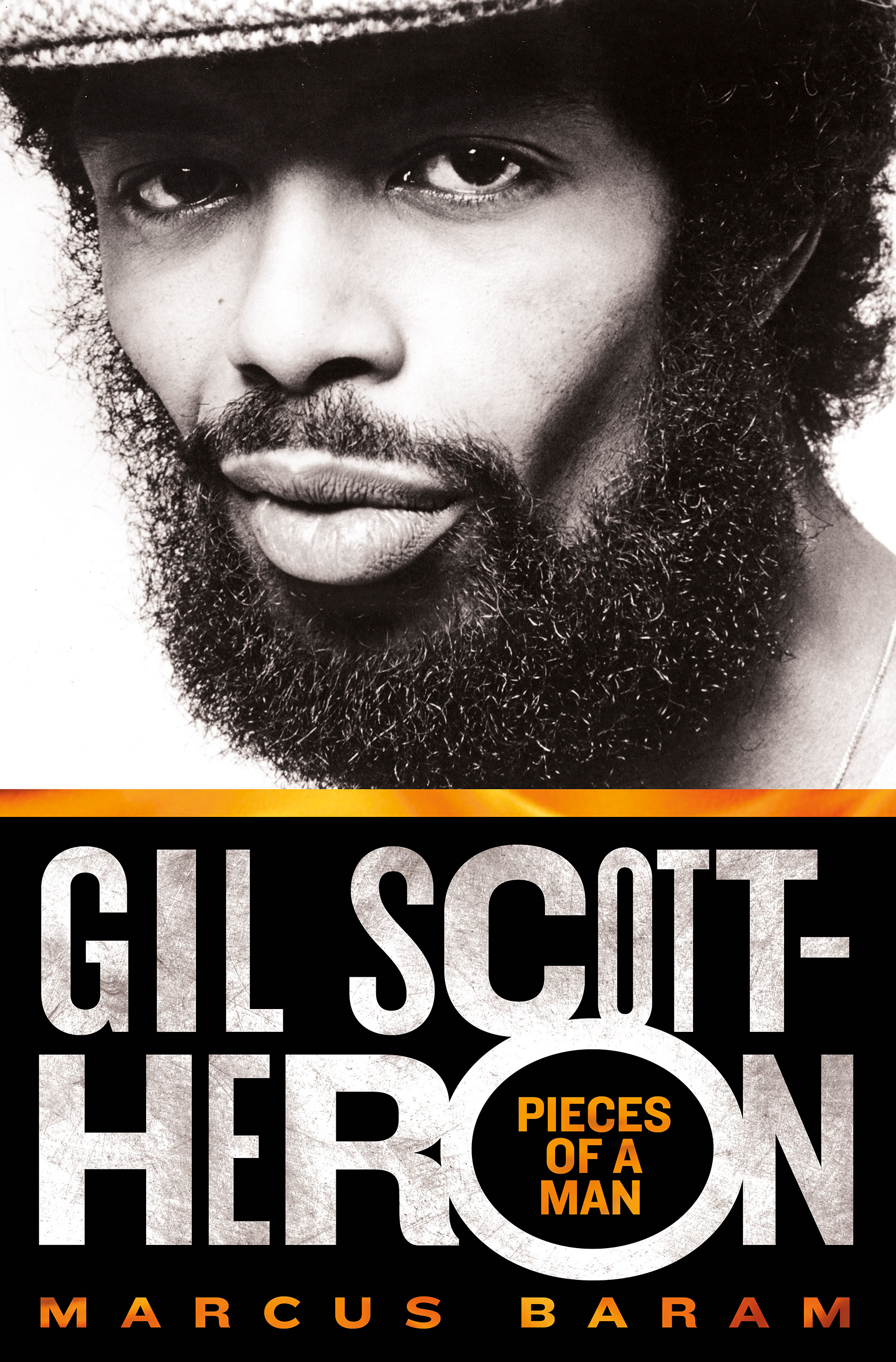

Author Marcus Baram Discusses New Gil Scott-Heron Bio “Pieces Of A Man”

11.17.2014

MUSIC

“You hear that?” Kanye West asked on Late Registration‘s “Crack Music.” “What Gil Scott was hearing’/when our heroes and heroines got hooked on heroin.”

While hip-hop has done much to revitalize the late Gil Scott-Heron and his music and poetry, it doesn’t undo the fact that although he is one of America’s greatest folk artists, he has tragically flown under the radar. Thus, author Marcus Baram, who met Scott-Heron several times and profiled him in 2008 for New York Magazine, uncovers much of what has gone overlooked and misunderstood in Pieces Of A Man, the first biography about the man who declared that “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.”

“I talk to so many people who are hip to music and culturally aware, and a lot of them have never heard of Gil,” says Baram. “Then, I’m also surprised by other people who I wouldn’t expect to know much and right away they’re like, ‘Oh yeah, Gil, I saw him a few years ago. I love him!’ He does have this cult following and I hope that this book exposes him to a lot more people and inspires folks to buy his records, his books and his poetry. He has a strong message and a lot to say.”

Life+Times: What were the questions you wanted to answer and things you wanted to uncover about Gil in the book?

Marcus Baram: A lot of it was his road to becoming a musician. I knew he started off as a writer and wrote a novel before he did his first album and wrote a lot of poetry. I wanted to know how he became a musician. And then I wanted to know about his own political awareness, his own background, how he learned about issues, and how he felt that music could be a way to address his concerns and some of the injustice that he saw and witnessed. And then, one question people always have with Gil is, “What happened?” Here he is in the ‘70s putting out an album almost every year, including a lot of top hits like “The Bottle” and “Johannesburg,” and then in the ‘80s he starts to fade away, then he disappears for a lot of people. A lot of people grew up with him and were influenced by him in the ‘70s, we saw him on tour when he joined Stevie Wonder on the “Hotter Than July” tour in ’81 to raise support for making MLK Day a national holiday, then he disappeared in the late-80s and ’90s. There were rumors about what happened to him and I wanted to talk to him about it honestly, like, “What happened?” I talked to him several times backstage at shows and spent a day with him at his place in 2008, but I obviously wish I had a lot more time to really answer some of the questions. In some ways, it’s a blessing and a curse, because when he was alive he was very self-defecating, he always minimized his role, like, “Oh, I’m just a blues-singing piano player.” He wouldn’t acknowledge his importance or legacy. He was also very personal. He kept a lot of things, especially about love, relationships, his childhood, very close and private. So, when he passed, people were a little more freed up to talk about him. There were a lot of people who probably would not have talked to me when Gil was alive, but when he passed, they could talk – not negatively – but in ways that were a little more open and honest.

L+T: Describe the research process you went through and how you were able to find out so much information about him going all the way back to his childhood in Jackson, Mississippi.

MB: Certain parts were easier than others, like reaching out to his classmates at Lincoln University (in Pennsylvania). He basically met the members of the band from Brian Jackson to Eddie “Ade” Knowles in college, so that was pretty easy to reach out to them and get them to talk to me. Other parts were more complicated like having to go to Jackson and go to the historical society and find that information about his mother’s family. His grandfather at one time pitched against Satchel Paige, details like that are a little more historical and take some digging, and a lot of it is not in documents. As a reporter, I always try to dig as deep as possible. Obviously, first there’s a lot online, then you go to libraries and dig up old newspapers and archives. Then, at some point, it’s about the people. People can be the most invaluable because they have a lot of their own memories and documents. Anybody you talk to, you ask them, “Hey, can you recommend someone else I can talk to?” They give you three more names. Then it snowballs and eventually you’re talking to dozens of people.

L+T: What or who would you say were his major influences as a musician based on the research that you did?

MB: Early on in the ‘50s when he was in Jackson, a lot of it was through blues that was on the radio. There were some nearby Memphis stations that he listened to a lot. He has some relatives from Brooklyn who would come down and visit, and they’d bring down Thelonius Monk records, Miles Davis records, so he had early education in jazz and blues and gospel. His grandmother raised him, she went to church and she’d have him play piano in church. Later when he came to New York and lived with his mom in the Chelsea neighborhood – a very mixed neighborhood with a lot of Latinos – he was exposed to a lot of salsa and latin jazz, and folk music that you hear in coffeehouses and The Last Poets. In college, he was exposed to a lot of the experimental jazz and free jazz like Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp, obviously John Coltrane. Coltrane was a huge influence. When he first heard A Love Supreme, that transformed his life. He talked about it several times, it made him realize that you can be an artist and have integrity and be true to yourself and still succeed. You don’t have to accommodate what is popular, you can have integrity.

L+T: And what about his political influences?

MB: In the very beginning, he was very influenced by the Civil Rights struggle growing up in the ‘50s in Jackson and being one of the first students to integrate the schools in Jackson. So, he was always aware of that. His grandmother would talk about it a lot, she would talk about the murder of Medgar Evers. In the ‘60s, the anti-war movement was happening and he was affected by that, then during college, the Kent St. shootings and the shootings at Jackson St. University all made him aware of not just racial injustice, but injustice in general. He saw corruption in Washington, how inequality was perpetuated, maybe not through Jim Crow, but through policies and the power structure. He was one of first people to speak and sing about apartheid in Johannesburg long before it became an issue on college campuses – Barack Obama was actually a big Gil fan in college when he was at Occidental College in the early 80s, he and the classmates that I talked to would spend hours listening to Gil. He was friends with Stokely Carmichael and the Black Panthers, but Gil always wanted to be independent. Minister Farrakhan wanted him to convert and join The Nation and obviously the Black Panthers were very interested in him, he was like their musical prince. But he never wanted to join a group. He was always about listening to people in the community and not just the Black community. He addressed coalminers in his song “Three Miles Down,” illegal immigrants struggling in the U.S. in his song “Alien,” African countries in “Liberation Song”.

L+T: Talk about his relationship with hip-hop.

MB: In the very beginning, he was a little resistant, I think, being labeled as one of the godfathers of rap. He was a little put off by what he perceived as some of the misogyny and violence in some of the lyrics, but eventually, especially hooking up in the late-90s with Mos Def, Common, he had this long relationship with Chuck D over the years, and then with Kanye later, he saw that they were heirs to his musical legacy. Hip-hop artists were doing “message music,” where there is a lot of socially conscious lyrics and political awareness were matched to a good beat. He was influenced by hip-hop, like when he did the song “Re-Ron” in the mid-80’s, which had a kind of computerized, syncopated beat. In the mid-90’s with Spirits, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, from A Tribe Called Quest, produced one of those tracks.

L+T: While hip-hop has helped him regain some relevance in recent years, why has his legacy flown under the radar in many ways? He’s one of the great American folk artists.

MB: It’s very unfortunate. Part of it is just that Americans move fast. Things that were very popular 30 years ago are now forgotten about. Also, the music industry changed. In the ‘70s, if you were an artist who was a bit quirky, doing something different, speaking out politically, trying to upset the establishment, you could have a platform and get a record deal. By the ‘80s, it changed. It was a lot more focused on big, slick productions and studios were only focused on the big selling artists and the big pop names. They didn’t care about cultivating the smaller artists and Gil was really hurt by that. Arista and Clive Davis were great when they discovered him, but they also, I think, wanted him to be a little bit more pop. They wanted him to start bringing in disco and pop, and Gil is stubborn, he didn’t want to do that. He wanted to do his music. Unfortunately, the studios didn’t encourage and support that. With his own addiction problems, he disappeared for a long time. He came back in the ‘90s with Spirits and showed up one some top-10 lists, but it was almost too late to really come back. Then he fell off again for another 15 years until I’m New Here. America in the ‘70s was much more focused on political movements, discussion about issues and by the ‘80s people were more materialistic and didn’t care to talk about that as much. That also hurt him. So, it was a real combination of things.

Pieces Of A Man is available now.