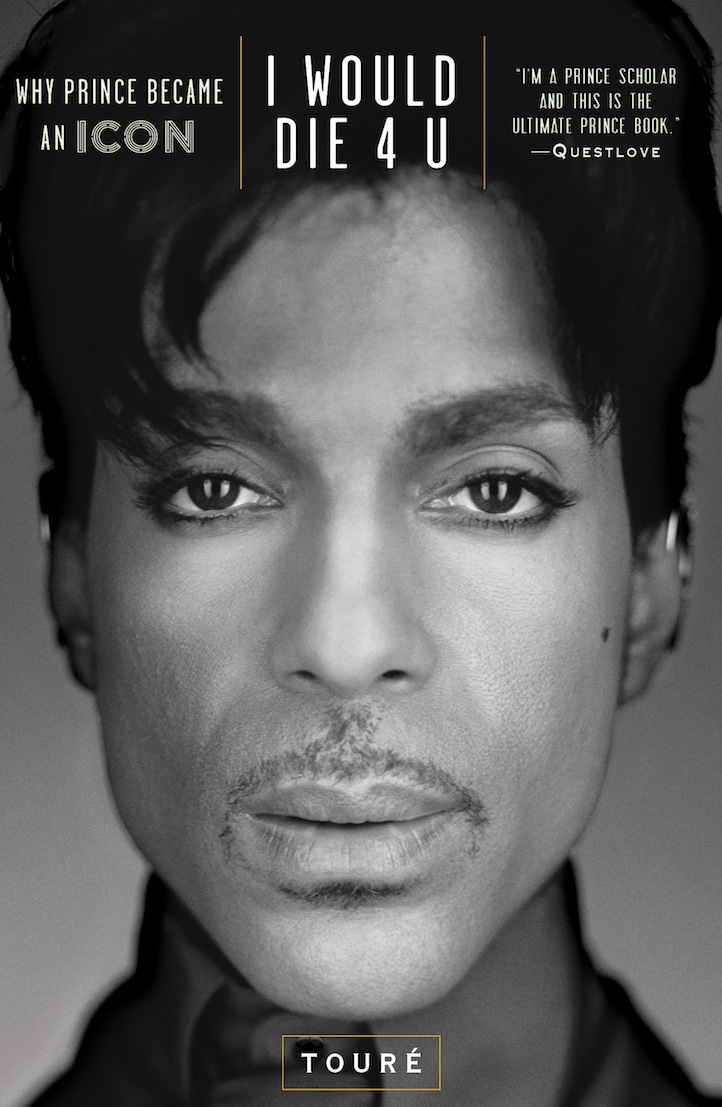

Touré Talks About His New Prince Book, “I Would Die 4 U”

03.19.2013

MUSIC

Prince is one of the music’s most talented and revered artists, and at the same time, also one of its greatest mysteries. In his new book, I Would Die 4 U: How Prince Became An Icon, popular author, journalist, TV personality and culture critic Touré digs into what allowed Prince to emerge as a revolutionary pop artist transcending race and all other boundaries to become the voice of a generation. Based on three lectures he gave at Harvard a year ago, Touré discusses how and why Prince is an icon for Generation X in particular, a product of his times – namely MTV’s launch, growing sexual awareness and porn chic in the mainstream and improved racial equality – and the constant allusions to religion in his music.

Ultimately he argues that, “by virtue of his reach, his seductive appeal, and his artful archness, Prince is not only a master many times over of pop, soul, and rock music, but also one of history’s most significant religious artists.” I Would Die 4 U contains Touré’s personal anecdotes from his own experience interviewing Prince years ago, as well as interviews with Paisley Park Records president Alan Leeds, Revolution Guitarist Dex Dickerson, Purple Rain sound engineer Susan Rogers, Questlove and others.

Life+Times got a chance to talk with Touré about his latest book and The Artist Formerly Known As Prince.

Life+Times: Talk about going from your lectures at Harvard to making this a full-blown book, and why you decided to do that.

Touré: Well, I wrote the lectures with an eye toward making it become a book. That was always my plan. I didn’t want to spend a year digging into a really interesting subject then not go all the way and make it a book. Skip Gates invited me to these lectures and I wanted to do something that I thought was really interesting and that I’d be happy spending a year focusing on. After I did the lectures, as a writer, it just took a little shaping in terms of a couple of things that would change from a spoken document to a written document. The lectures were one lecture per day over three days, so you end the lecture saying things to try to make sure people will come back tomorrow. In terms of writing, you don’t to do that, so I sort cleaned up the end of chapters like that. And, given a little more time, I had the opportunity to get more people on the phone, find more people and interview more folks. So I was able to broaden my discussion by finding new people.

L+T: The book brings everything together by saying Prince’s talk about sex is a way to lure people into a greater message. Did you know that going in, or did you find that out as you researched?

Touré: That was definitely a sort of revelation that came about as I was researching. It’s something that I figured out out as I was reading through, looking at the amount of religion and sexuality in his work. There’s a number of things that I discovered about him as I was researching. I knew a lot but I learned a lot, and it’s always exciting as a writer when you can learn as you’re researching a subject.

L+T: What were some other new revelations that you had?

Touré: I had not really understood “Purple Rain.” Like everybody, I looked at it as this great song, [but] I really didn’t have any idea what he was talking about. Talking to Questlove, Bible scholars and some other people, they started pointing to baptism and water as a baptism symbol. It’s sort of oblique, but if you read really hard, there’s a present story of a person who wants redemption because this relationship is breaking up, but they still love that person. They did everything right in the relationship but the relationship has to end. You want to be sort of blessed in that moment, redeemed in that moment, like, “Hey, you’re not a bad person, it’s ashamed it had to end, but it had to.” Then that third verse is so crucial, where Prince is kind of saying, “follow me, I am a messiah figure.” It’s extremely powerful and important in trying to understand who he is.

L+T: One of the most fascinating parts is when you talk about him “passing” as biracial. Can you expand on that?

Touré: Sure. His mother is Black. I don’t have a photograph of her, but several people who met her or spoke to her told me she was Black. Think about it ethnographically: Mattie Shaw, from Louisiana, grew up in the projects, known for playing basketball very well, moves to Minneapolis, becomes a jazz singer in her early 20s, and falls in love with a marries a much older Black band leader who already had a family. It sounds like a sister to me. If that was the only thing I had, that would be circumstantial. There were no miscegenation laws in Minneapolis that I could find at that time but it was not usual. Minneapolis is one of the places I’m told that was ahead of the curve on those issues for a long time, but still, if we apply occam’s razor, it appears most likely that his mother was Black. And there’s no conversation that his father was not Black. Obviously, [he’s] very light and mixed at some level, but generally, when we’re talking about mixed or biracial, we’re talking about one parent is a different race, and that is, from all the evidence we have, not the case. But, Prince very much wanted to have the largest possible audience that he could have. So, he tells a few of the first reporters who interview him that his mother is white, Italian. The way journalism goes, [if] the first three people interview somebody, report a certain fact, you may not keep asking; so if you’re the sixth, seventh, eighth person to interview him and several articles have said this is a fact – “he’s mixed, his mother’s white” – you wouldn’t keep asking that question. That’s just how we are. You might ask about being mixed, and now you’re helping him live the fantasy. Putting a white woman as his mother in Purple Rain helped push that further. What he was trying to do was not run away from being Black, he very much loved being Black and his music is unquestionably Black; but he wanted access to the larger mass culture and he also wanted to not be tied by the expectations of what being a Black recording artist would be. He wanted to break out of those boundaries. To want that in the late ’70s-early ’80s was very revolutionary, unusual and unexpected. For him to be able to break out, he had to be demanding of the right to do rock-and-roll as well as funk and soul. Part of the sell within that was saying, “I’m mixed,” or, “Don’t put me in the box.” [He would] not do certain tours that would have him on the undercard for certain artists who would pigeonhole him. He would do tours where he would do a sort of white venue, then do a traditionally Black venue, so he’s hitting both sides. Record businesses would have a sort of segregation where there would be a Black music department which would market you to Black media, try to get you on the urban charts, etc., that would typically have smaller staffs and smaller budgets as opposed to the pop [departments], which would be larger budgets, larger staffs, larger potential to become a superstar which was always his goal. He’s passing for mixed as an attempt to gain some white-skin privilege or mixed-skin privilege – but that’s not a thing, you wouldn’t benefit from being mixed, you’d benefit from being partially white. But in no way is he rejecting or running from Blackness. I think some of us are rightly suspicious, nervous, anxious, upset about people who pass, but I think a lot of the time, they are not hateful or rejecting Blackness. They see a loophole in the social construct of race and they say, well, “If I rewrite myself (which is a typical American thing), then I can have access to white-skin privilege and see how far I can go in this world. There’s no boundaries in this world as opposed to dealing with the boundaries that have been imposed on us living with white supremacy and the expectations of us.”

L+T: Was there any backlash from Black audiences or Black radio for that?

Touré: Not that I know of. I think there were definitely some Black people who might have been like, “It’s a little too rock-and-roll for my taste,” especially in the era of “Purple Rain,” which is a tad bit silly in that we created rock-and-roll. If you look at Controversy and 1999, they’re very soulful, funky albums, Around The World In A Day had some ’60s-inflected soul, then you get back to LoveSexy, Sign O’ The Times, there sort of albums, it’s very, very souful. Some funk, but lots of soul. But that piece, I don’t think we realized it, because a lot of people thought he was mixed. I think it took a while for people to realize, “Oh, he was teasing us.” But what he was really doing was trying to escape the boundaries of demographics, of the sayings, “you’re Black, ergo X, Y, Z, or you’re female, ergo X, Y, Z.” He wanted to be free and you see that in [his questions] like, “Am I straight or gay? Male or female? Black or white?” He’s really messed with you. That’s sort of an ’80s thing, “I’m not going to let the demographics determine who I am and how I’m perceived.”

L+T: How important was it for him to be from Minnesota and how did that shape his outlook?

Touré: It definitely shaped him in several ways. It’s a place where there was a lot of connection between Black and white cultures. A lot of mixed relationships, so that was very natural in his experience. He was not part of a big city, so in a way he’s able to be part of this music culture, but in a way, he’s able to fly under the radar as opposed to growing up in L.A., New York, what have you. He was also exposed to a lot a great radio stations, but they’re pop radio stations. They didn’t have all the stations that we have in New York or L.A., so a lot of people talked about the impact that the pop stations had on him and how the records that he heard – these pop records – influenced who he became.

L+T: A couple of times in the book you reference Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and the importance of timing. If Prince hits five years earlier or five years later, are we having this conversation?

Touré: I think so. It’s impossible to know, but I think so because the talent would still be there. But what I’m talking about is definitely affected and influenced by [him] growing up at a time when gospel is becoming secular music and is played seven days a week, and he’s able to interact with Rick James, George Clinton, Al Green and those sort of people. Then, when he emerges, he’s able to interact with the highly sexualized culture of the ’80s and be a natural progression from James, Clinton, James Brown, etc. It’s impossible to know. I think yes, we’d still be talking about him because the level of talent was such that he would still be famous, but would he be the same level of icon, well that’s un-knowable.

I Would Die 4 U: How Prince Became An Icon by Touré is available March 19th on Amazon.