Respect The Shooter: Jonathan Mannion

11.07.2013

ART & DESIGN

In August, hip-hop’s favorite photographer, Jonathan Mannion celebrated the 10-year anniversary of his famed Mannion Studios. The milestone, however, proved bittersweet. Due to the impending demolition of the building housing the studio, this anniversary would be the its last, but for Mannion this isn’t a somber moment. “It’s a celebration, and not any kind of down moment that it’s the end. It’s never the end,” he told Life+Times during our recent visit to the studio.

Serving as his headquarters during the last decade, Mannion Studios became the backdrop for many unforgettable images featuring the likes of Kanye West, Drake, Dwayne Wade and many others. As we sat down with the legendary photographer (and his bulldog, Pocket) to discuss the closing of the space, he also spoke on shooting JAY Z‘s The Black Album, Kanye West and his love of OutKast.

Life + Times: For you, is the closing of Mannion Studios the ending of an era or the beginning of a new chapter?

Jonathan Mannion: I feel it’s sort of the changing of “Jonathan Mannion” and what I’m going to be next, which I think is a cool thing. When I heard that the studio was going to come down I thought of it as an inconvenience. I wasn’t in denial, but I was kind of pissed off. You know? It’s a really dope and unique spot, but I think God has a way of telling you that you’re on to bigger things. When you’re unable to figure out how to shift quick enough for the bigger plan of what you’re intended to do or what you’re put here to do it just pulls the carpet out from under you. That’s always been my perspective. The work that I’ve done is incredible and certainly in the moment it’s unbelievable to create with somebody, but it’s not precious to me. It’s not like I have to protect it all. I want to set it free, so I do the shoot and I let it go. The people will enjoy it or not and that’s cool. I know what I’ve done, but I’m always ready for that next thing. I’ve tried to apply that mentality to the next phase of what’s happening and really take this moment. I’m now ready to let this go and let this fly, because I know that there’s something even bigger happening right behind it.

L+T: You gathered a few friends to commemorate the studio’s closing. How did that come together?

JM: I invited people who I thought it would be important enough for them to be in the space one last time. The people who were really a support structure of the movement like a Jeff Staple or [Hot 97’s] Ebro or [Roc Nation’s] Lenny S., etc were invited over. I didn’t tell them why they were coming. I told them I was having a party. They thought they were just coming to chill. Modelo Especial was kind enough to throw some beer our way and help create this great vibe. That night I photographed about fifty people and gave them a print at the end to walk away with. Seeing all of these people come out and have a good time made me realize that I really do something special that people care about and that the support that I’ve always known that I’ve had has manifested itself concretely.

L+T: You’ve said that this was the beginning of the end, so are there more events or projects planned to commemorate the studio’s closing?

JM: The doors ain’t shut. We have a lot more partying to do. I know that I’m going to do a dinner for about twenty or thirty of my closest friends and the people who have had a huge impact on me. I want to do something that gives back to the people that have been supportive. I know people wouldn’t typically ask to buy some of my prints, so I may have it where you can come by the studio and leave with a print for free. For me to hoard all of this stuff does me no good. I also want to do a destruction party in here. I want to get some painters in here to tag the walls up. It would be unbelievable for me to have like five incredible artists to just cover the studio from the floor to the ceiling and then have people come and cut out pieces of the wall. That’s the kind of shit I want to do. That would mean a lot to me. If it’s all coming to the ground it doesn’t matter what we do. I’d have a slow-motion camera taping the empty space before and as the madness is happening. I’d invite people for the celebration and they’d get to take a fucking chunk of the wall. We could even do something where people would have to donate $100 to a charity or something. It’s a way to do this that everybody wins, because everybody needs each other.

L+T: Kanye West was the first artist you photographed at Mannion Studios. This was a pre-College Dropout Kanye. At the time, did you have any indication that you were working with someone who would soon be so influential?

JM: I think we knew that before he even came over here to shoot. He didn’t get that Fader cover because of some sort of publicity stunt. The people over at Fader have always been music fiends and have always been so on top of what’s happening. ‘Ye was making waves – most good and some bad. He was called arrogant, but if you don’t believe in yourself who’s going to believe in you? Ultimately, despite whether you like him or hate him personally or what he says and how he says it or whether he has gold fronts on his teeth he still executes and challenges himself as an artist to rise to the occasion. Some people say they don’t like Yeezus, but you can’t deny that it’s a complete body of work. It’s a total thought out and fluid project. I really feel like him being in this space was a very special way to kick it off. I actually want to shoot him as my closing statement too. I feel like that’ll be the only way to go out.

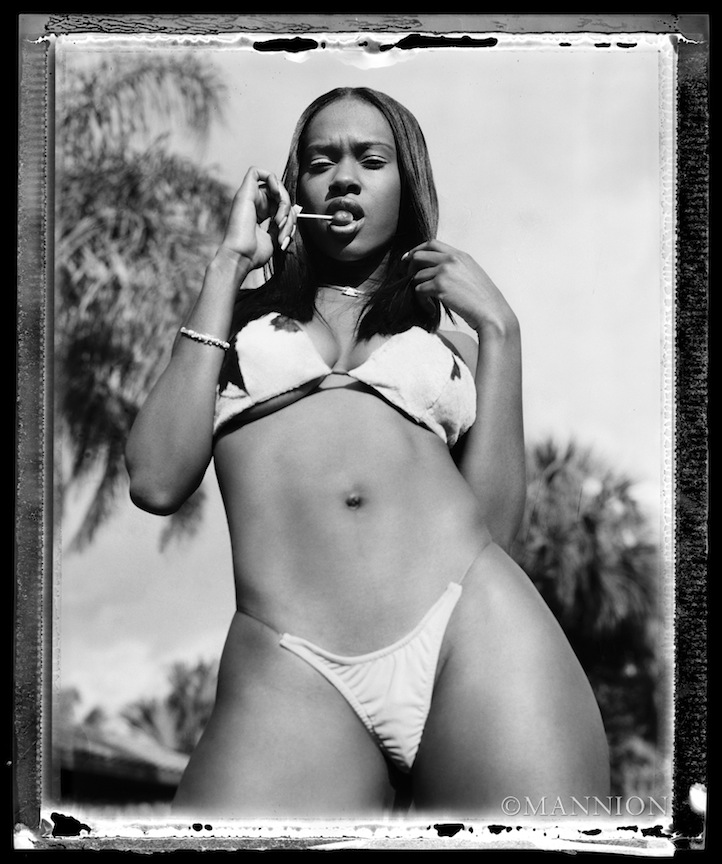

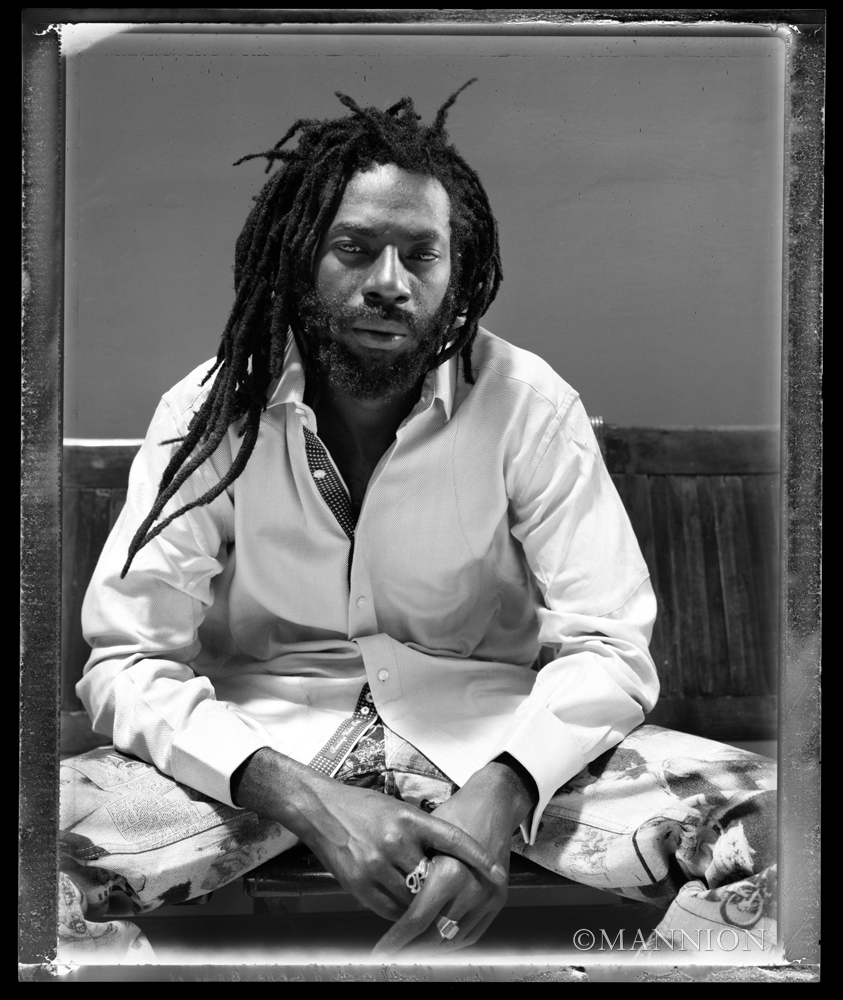

L+T: With your Rough Around the Edges: The 665 Polaroid exhibit you paid homage to the now discontinued film. Why was shooting with that film so special to you?

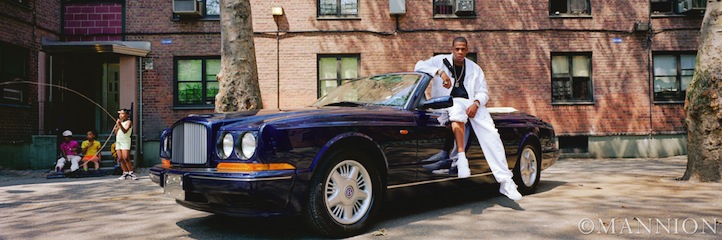

JM: There was an era of the 665 Polaroid that finished when the company went bankrupt, so you’ll never be able to buy that film ever again, unless it’s on eBay or something. I have such a body of work that falls just within those Polaroids. It was enough to gather fifty incredible images of Eminem, Buju Banton, JAY Z, Kanye and many others and be able to put together a cohesive body of work that really gives people an understanding that I know my craft. The Polaroid was our version of a digital camera, because we got to see the shot right then and have a negative of it that we could print. That was everything to me. I’m very, very passionate about my craft and my understanding. You can put any camera from any era in my hands and I’m going to rock it. Most kids haven’t ever rolled a roll of 35mm film into a camera. It’s like digiography these days, which is cool. I’m playing that game too. I haven’t shot film too much recently, but I did shoot Drake’s recent XXL cover using Polaroid and we kept the border in the shot to be able to show that.

L+T: Whether through conversations or listening to their music, you find a way to connect with the artists you shoot. Does building that rapport help in getting such great shots?

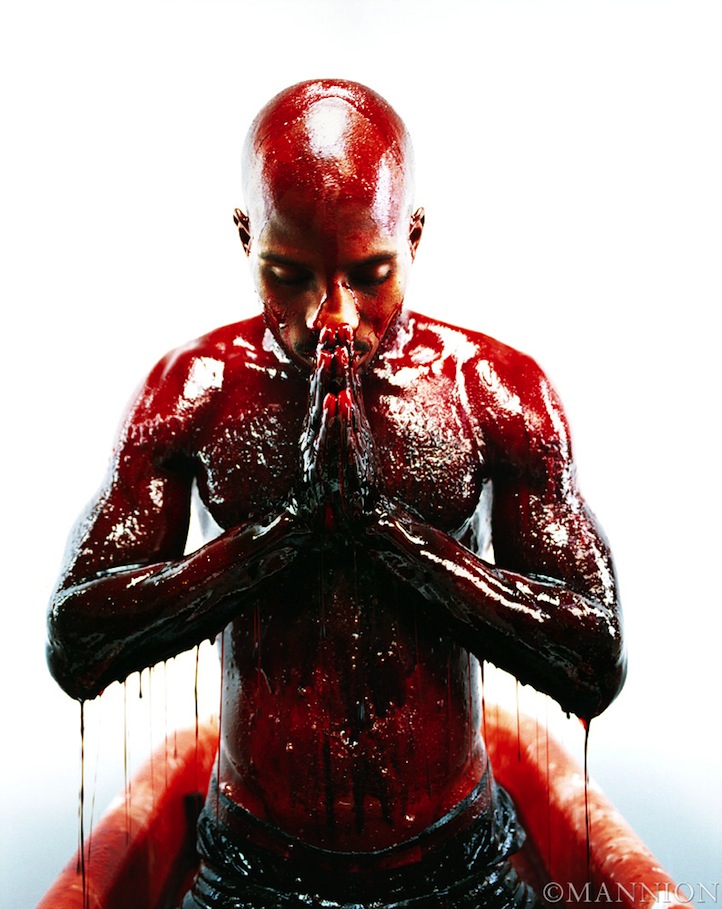

JM: Yeah. It’s a great way to tell your perspective, because it all boils down to the motivation behind your vision, imparting that on someone else and making it become their vision. There are a lot of different ways that I work. Sometimes I can actually sit and have a conversation with the artist. For The Game’s The Documentary he told me that he wanted the cover to be really, really West coast, but to also pay homage to those who paved the way. That was an ideal situation, because I did get to have a dialogue back and forth with him. We talked about who his favorite MCs were and how he wanted to incorporate that. Then there’s a situation like with DMX’s Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood album where I didn’t really get a chance to speak with DMX before the shoot. I sort of walked into that one blind with my ideas. Then there are people like Big Boi that will call me up like “Yo it’s time to listen to the album.” While I’m listening to the entire album I’ll scribble notes and start getting ideas ready.

L+T: Has there ever been an album cover where you felt the shots were incredible, but the music wasn’t nearly as good? If so, how do you feel in those instances?

JM: I feel fucked up that they devalue my work. Those sucka MCs should’ve been better [laughs]. I’m just kidding. I say that jokingly, but I think my job as a visual practitioner, as a visionary, as a photographer, as a creative director or whatever is to make that person look incredible. It’s ideal when I can vibe to the music and feel something, but really my job is to make you look great. That’s what I do. I don’t have to cosign your music. I don’t have to love it. I’ve literally asked certain MCs what their favorite song on the album was and they’ll say “I love it all. It’s all dope,” but they were playing their records over and over and over on that particular day and there wasn’t anything that stood out to me. If the music is wack, that’s on them. The people will judge them for that, but I cosign people. My goal is to take the best picture of that person in that moment. I put so much pressure on my shoulders, because I know this is their project that defines a particular moment. I have to make sure it all looks the way it’s supposed to look.

L+T: The 10th anniversary of The Black Album is approaching. Was your approach to that album different from previous JAY Z albums, since it was slated to be his last album?

JM: The way the situation happened with The Black Album is that the image existed already. It was originally taken during The Blueprint shoot and they just repurposed it as guidance. Everybody just fell in love with it. Jay was very adamant about not wanting to do a shoot, but everybody at the label knew that he needed images, so I made it really easy for them to work with me. He’s quite brilliant in general, but especially in terms of knowing what feels right to him, so I think that’s how that cover came to be. It was also me fighting to be in the room to be able to execute a final statement to at least say that I shot that album. We put something together, but it wasn’t as other album covers had gone before. He wasn’t mad or there wasn’t anything wrong, but there was just this energy in the room. Normally shoots with him are natural and easy, but this one was more of a battle. It wasn’t me verses him, but us verses the situation. Things had always gelled for every shoot. It was like divine intervention and things would just drop in front of us, because we were doing the right thing in the right moment. This one was something that was more of a challenge. I’m just glad I fought to be a part of it, because it just finished off a run. I think our run is one of the most epic runs for a photographer working with an artist.

L+T: You’ve said that there’s only one chance to make a first impression. With Reasonable Doubt being not only JAY Z’s first album, but also the first album cover you shot, did you guys make the right first impression?

JM: Is that even a question? [Laughs] I think we hit it out of the park. There is no doubt in my mind that what we collaborated on in that moment was perfect for that moment. It was a humble beginning and it was something that really established him as an artist who created a project that was complete musically. I believed I doing something that was still of him, but still conceptual. It was a visual cover in the sense of it playing into a time-period, but it wasn’t gimmicky. And ultimately, he just looked sharp. It was just perfect for Jay. I think what we made holds the number-one position in a lot of people’s hearts as the dopest album cover of the last thirty years. It was an amazing experience. Like that’s how I start? How I enter the game? It’s like I walked into the park and hit a home run and I’ve been hitting home runs ever since. It was an amazing way to kick it all off.

When the album was called Heir to the Throne I came with like fifty ideas for what I would do for that concept. I actually have the piece of paper where I wrote the original notes on what I wanted to do for Heir to the Throne and Reasonable Doubt to this day. When they called me saying they had changed the title and needed me to come up with some new ideas is when I came with visual references of old police photos from the 1930’s and style references from that era. I think Jay was still on the Versace silk shirt on a speed boat and Scarface kind of thing, but I felt like that wasn’t Brooklyn. John Gotti was Brooklyn.

L+T: If we’re only focusing on the music, what would you say is your favorite album that you’ve shot?

JM: I shot OutKast for Fader when Stankonia dropped. I shot them for The Source when ATLiens dropped. Those are two of my favorite albums. I just love those albums. Even though those weren’t album covers those images were associated with those albums [Laughs]. But to really answer your question I would have to say Vol. 2… Hard Knock Life. That album was fucking nuts. I remember going to the listening party and him really being proud of it. That was such a complete project. Anywhere I went in the country I heard that album. I was shooting Uncle Luke in Miami and that album was bumping. I shot Stephon Marbury in Atlanta and he had bought like six copies and put them in every one of his cars and his team’s cars, so he would always hear it. That was really an amazing moment in time.

All images courtesy of Jonathan Mannion. Used with permission.