Hiatus Kaiyote Talks Growing Global Buzz

07.29.2013

MUSIC

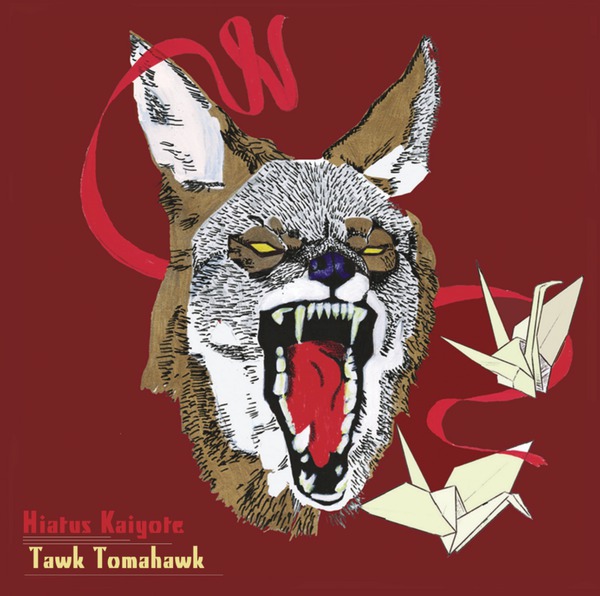

The power of the Web has been in full effect for Hiatus Kaiyote, a multidimensional band from Melbourne, Australia creating “future-soul” grooves. Since releasing their debut album Tawk Tomahawk in April 2012, word of the four person group has spread across the globe like wildfire thanks to co-signs from major artists and tastemakers including ?uestlove, Erykah Badu and Giles Peterson. Word of mouth was critical, but the selling point had to be the product; the music.

“We wanted it to be a cohesive piece rather than song end, stop, song end, stop. I feel like everybody’s looking for hit singles nowadays and we wanted to release something that was a piece,” guitarist and vocalist Nai Palm said of Tawk Tomahawk.

Riding momentum from their independent success, the band was discovered by Salaam Remi and signed to his Flying Buddha record label, and a subsequent re-release of the album (which includes a Q-Tip feature) has helped get it in the hands of those who couldn’t find it before. They’ve performed in the United States previously, but will return later this summer, including dates with D’Angelo and Badu, Shuggie Otis and José James.

Life+Times caught up with Nai Palm to discuss the origins of Hiatus Kaiyote and the path they’ve travelled thus far.

Life+Times: What does the name Hiatus Kaiyote mean?

Nai Palm: Well basically, “Kaiyote” is not a word. It’s a made up word, but it kind of sounds like peyote and coyote – it’s a word that involved the listeners creativity as to how they perceive it. So it reminds you of things but it’s nothing specific. When I looked it up on online it was like a bird appreciation society around the world, so for me that was a great omen, because I’m a bird lady. A hiatus is essentially a pause, it’s a moment in time. So, to me, a hiatus is taking a pause in your life to take in your surroundings, have a full panoramic view of your experiences and absorbing, and “kaiyote” is expressing them in a way involves the listeners creativity. It’s a duality with out music, as well. We don’t like to spell it out because if you can vaguely portray something, then it’s more likely that a broader variety of people can relate to it because they can find their own way in.

L+T: You just recently re-released the album and included a remix featuring Q-Tip.

NP: Yeah, we just put it online originally and it’s kind of blown up like wildfire. Badu picked it up, ?uestlove picked it up, Animal Collective, Jesse Johnson, etc. So, we’d kind of gotten the world’s attention but we weren’t signed to anybody and didn’t have any distribution deals. You couldn’t get a physical copy of anything. Through a really beautiful sequence of fate, we found Salaam Remi – or he found us – and he’s been working as an A&R for Sony, and they’ve given him the opportunity to start up his own label which is Flying Buddha. We always wanted to get our music out there, but the bottom line is that we continue to have our creative freedom and be able to record it the way [want]. People respond to our music because we’re doing what we’re doing, not because we’re working in a fancy studio or with certain producers. We want to do it ourselves. That was important to us and Salaam is such a tastemaker and skillful producer, I think he really resonated with that and was really supportive of our vision. We’re the first band to be signed to his new label and as a result of that, it’s been distributed around the world, we’re with the CAA Agency. The Q-Tip collaboration came because he’s known Salaam for years. He brought it to him and I wrote Q-Tip an email about the origins of the song because Nakamarra is an indigenous skin name and there’s a lot indigenous Australian cultural references in there. It’s cool to have a high guy on there dropping a verse, but I really wanted them to be informed about the history of it because it’s pretty sacred to us. So, when I emailed Q-Tip his interest peaked which is an incredible sign. He’s iconic, and we’re all big Tribe fans, so it was pretty amazing that we were able to come together. It was a trip recording my harmonies with such a legendary voice. Because we’ve already released Tawk Tomahawk online, [including the Q-Tip remix] was kind of to give an extra incentive to people that might already have the record.

L+T: What do you think was the tipping point for you all that’s led to this global buzz?

NP: I feel like it was less of a climatic moment and more of a domino effect. We did a show in Australia with Taylor McFerrin who’s on [the label] Brainfeeder – we’ve only been together for two-and-a-half years so it was pretty early on – he dug it. He was on a European tour and he tweeted about the band, then this French website picked it up. Taylor gave our record to Giles Peterson and Anthony Valadez, who’s a DJ on [New York radio station] KCRW. Anthony Valadez had been giving us mad love as far as getting a lot of spins on KCRW, so Animal Collective heard it on the radio because they live in LA, they showed Angel [Deradoorian] from Dirty Projectors which is another incredible, then Angel is friends with ?uestlove, so she showed it to him. And then he’s been an ambassador for us which is pretty amazing because he doesn’t really do that. He’s stated publicly that he’s not one to really promote a lot of music because he’s exposed to so much and if he does then he’s Craigslist, but he’s been amazingly supportive of us. I’m not really sure how Badu heard – probably through James Poyser because we met all of The Roots and she works a lot with James. You realize more and more that everybody’s interconnected musically. That’s kind of how it’s gotten out there and the response has been amazing. I’m a massive Badu fan, so it’s pretty crazy that all these people that are ambassadors for the band are people we really admire. It makes you feel like you’re on the right path and all you gotta do it keep doing what you already love and people respect you for that.

L+T: How do you all get along and work together in the studio and performing live?

NP: There’s myself, Nai Palm. The project started with my compositions just with guitar, vocals and songwriting. Then I met Paul Bender, who’s the bass player and also produces. Basically, he charted all my stuff out so that we could find other musicians to work with. Myself and and Pez [Perrin Moss], the drummer and also a producer, we don’t have any formal training, but Bender and Simon Mavin, on keys and synths, they both studied jazz and classical music pretty extensively. So, it’s this really beautiful mixing pot of intuition versus theory. We’re all very intuitive players and I feel like I’m growing musically just by being exposed to musicians that can really understand it on a cognitive level. I met Simon and Pez just around the Melbourne music scene. The Melbourne music scene is crazy. It’s thriving, it really is, there’s a lot of amazing shit going down. Everybody knows everybody and it just kind of came together. Once we had our first rehearsal, you could feel the sonic chemistry. It wasn’t just like, ‘Oh great, now I’ve got a bunch of musicians that I can make do my songs,’ it was like, ‘Wow, I really want this to evolve beyond me and have the creative influence of everybody and be a unit. Like a Transformer, Voltron kind of vibe.’ I feel like it’s really come together. Recording the album was all done at a home studio, Bender and Pez both [put in] extensive hours tweaking it and mixing it, putting jet sounds, frogs from Indonesia and random textures and stuff. With the writing, recording and live sides of it, there’s a different approach for each section of the song and the whole project. Our live interpretation of that, because we’re constantly trying to challenge and reinvent ourselves and explore each other sonically, is that we’re constantly reinventing the songs. So there’s a lot of flips and reinterpretations of songs we’ve written or recorded I guess because we’re all pretty heavily into hip-hop; so [we’re trying to] find that harmony between playing something live and having production. More and more with our live show, we’re trying to emulate sounds that may sound like they’ve been chopped up or effected or produced.

L+T: Your music has been described as “future-soul”. Not to put you in a box, but describe the sound that you have.

NP: To be honest, future-soul is another box really. But it’s helpful, otherwise people have no idea, so it’s does help to have some kind of genre ties to what you’re doing. Some people with music they’re trying to depict a certain genre, that’s what they’re about – like trying to portray something that’s throwback, that’s already occurred. For us, it’s more about exploring each other’s creativity. There’s a lot of influences in there. We all listen to a vast variety of different music, my mom was a dancer and contemporary choreographer, so from a really young age I was exposed to flamenco and predominantly soul. That’s how I can sing, growing up listening to Aretha Franklin, Stevie [Wonder] and stuff. That’s definitely heavily engrained in the tone for me vocally, but there’s a lot of other influences. Even beyond musical genres, you could be inspired by sounds in documentaries or a visual piece that stimulates something in your mind and you try to portray what you see visually sonically. It’s pretty broad with us because it’s a band, we’re a team, it’s four people who all have a very eclectic taste in music coming together. There’s definitely soul elements. Future-soul came across because it’s futuristic in a sense that we don’t really know what we’re doing. We’re not trying to achieve or portray anything, it’s more of an exploration, so I guess that’s where the future element comes into it. We’ve also had multidimensional, polyrhythmic gangster shit as a genre. You can call it whatever, but at the core it’s eclectic and without confinement.

L+T: What is hip-hop’s presence in Australia and how’s the influence it’s had on you?

NP: Well like everybody says, hip-hop’s almost bigger than religion nowadays, so it’s not just Australia, it’s global. I feel like it’s because the roots of hip-hop is the reaction to struggle, but in a really refined way. There’s a lot of people going through shit around the world so they can really resonate with that. There’s a lot of different art forms that are a reaction to oppression, but I think hip-hop is less of an aggressive reaction to it. It can still have heat, but it’s refined. The roots of that being jazz, as well, I feel like globally people relate to it because it’s the same story happening everywhere essentially. In Australia it’s pretty massive. Another reason is probably because [Australia] is a pretty Western country and it’s a very young country. Aside from the indigenous people here, it’s only been colonized for a couple hundred years, so there’s no real foundation of tradition. What I’m experiencing here in Europe is it’s so deep, people have so much tradition to draw from, whereas Australia is so young. Maybe that’s why hip-hop has really blown up there and people have adapted to it.

Tawk Tomahawk and more information about Hiatus Kaiyote is available here.