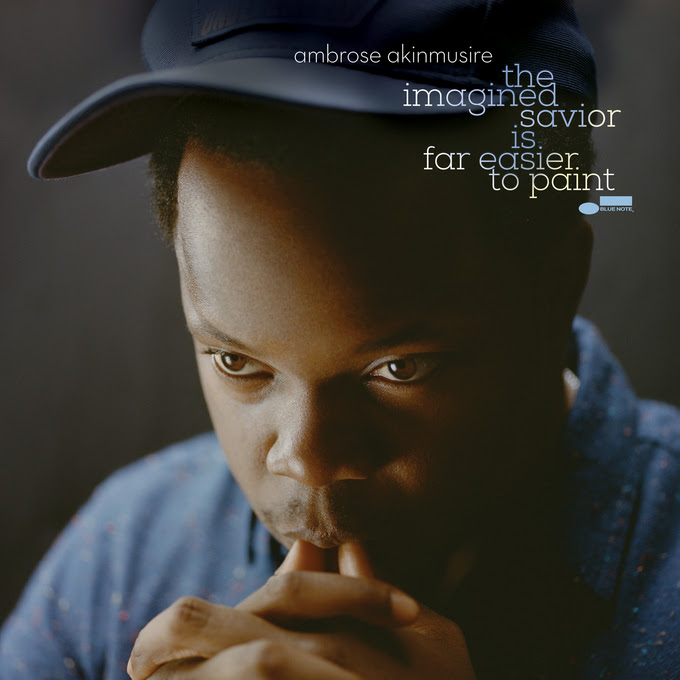

Composer Ambrose Akinmusire Speaks On New Album, Creating Characters, Oscar Grant & Trayvon Martin

03.11.2014

MUSIC

In many of Ambrose Akinmusire’s compositions, characters – both real and fictional – are the source of inspiration. Thus, each record is a story within itself. On his last album, the critically acclaimed When The Heart Emerges Glistening, this manifest itself in compositions like “My Name Is Oscar,” a tribute to Oscar Grant who was killed in Oakland just a few minutes from where Akinmusire grew up. On his newest album, the imagined savior is far easier to paint (out today), fictional characters Akinmusire created as well as the real-life tragedy of Trayon Martin, serve as the impetus and his trumpet leads the way.

“I do that just because I think that helps the form of the song, it helps the song lift off the page a little bit more,” he says. “Not that it’s easier for me to compose, but I definitely have more tools to work with.” With the help of a stellar supporting cast – tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, pianist Sam Harris, bassist Harrish Raghavan, drummer Justin Brown and guitarist Charles Altura – the imagined savior is a dark and deliberate work. Here, Life+Times talks with Akinmusire about his latest album, character creation, and how Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant influence his music.

Life+Times: The album title the imagined savior is far easier to paint: what does that mean and how did you decide on that?

Ambrose Akinmusire: Usually when I create an album or composition, I start with the title first. I write a story then I kind of sum up the story in a title. With this one, it was a little different. I came up with the musicians and the compositions and the characters before I came up with the title. I wrote about 40 or 50 titles down on paper and I kind of summed them up. That’s how I got this title. For me, the title doesn’t mean one specific thing. I feel like it’s a poem, I want it to be interpreted in as many ways as possible. I don’t want tell people what they should or shouldn’t feel. A lot of times a title can do that, and I think with this album, there are so many ways things can be interpreted, so I wanted to leave it more open.

L+T: So for you, how do you interpret the title?

AA: I can’t [laughs]. I don’t want to put it out there because then people will catch a hold of it and say, “Oh, this album is about that.” I can just tell you I always try to have my album titles have something to do with where I’m at in my life. Right now, I’m just working on being better human being, starting to try to focus more on some other roles that I may have neglected in my life. A lot of musicians just focus on being great musicians, and they don’t realize the different roles that are in their lives can actually help them. So, I’m just focusing on being a better son, a better friend. I’m really trying to figure out how to be there for people, how to be more in tune with nature, and be more of an artist as opposed to just a great musician. That’s where I’m at in my life right now and I think that’s also in the title. Sort of looking within yourself as opposed to looking for someone else for the answer.

L+T: You said creating this album and selecting the title was a different process than it has been in the past for you. Talk about that different approach and the overall tone. It seems like a darker record.

AA: Yeah, that’s exactly right. I just wanted to focus on being an artist and create something that could be looked at as a piece of art. From your first interaction with it – the photos, the title – I want it to feel like you’re on a journey, and it represents what’s going on now. A hundred years from now, I want someone to be able to pick up the album and look at it like, “Damn, that reflects 2014.” I feel like music and art in general – if you see JAY Z – is going to this area where everything is everything and art is just art. Genres are being melted into each other. I’m just trying to adhere to that. So you have tunes that could be considered modern classical; there’s a string piece with a flute and an Arco bass; another piece sounds like a southern Baptist [song]. I’m just trying to melt things into each other. It felt a little bit more honest, a little bit more natural than just trying to create that killing jazz album where I just play a bunch of trumpet stuff and deal with every solo the exact same way. I think that’s corny and I think that’s a lot of the reason that people are turned off by jazz because they have relate to what’s going on now in most cases, and it doesn’t reflect the times now. I’m really conscious about that and trying to be honest and not control what’s coming out of me, trying to be a conduit for this thing that’s higher than me. Not that that process is so different, but I think I’m a little more comfortable with it now.

L+T: There’s some interesting song titles, too. Did you come up with the song titles first, then create the compositions? Talk about naming these records.

AA: For this one, I came up with characters. So, “As We Fight (Willie Penrose),” [Penrose] is this dude who fought in the Vietnam War. A lot of these tunes were composed during the time of the Trayvon Martin case, that really had a big impact on me. [Penrose] is a Black guy who has some mental problems from the war and he’s sitting in a cabin in a rocking chair and he has a wife, and he’s watching the Trayvon Martin case on a black and white television screen. There’s something about that image that is really strong to me, and that’s what that composition was about. I create characters and stories, so a lot of these just had the [character’s] name, and the title is really about what the character is going through. In “Vartha”, Vartha is actually a girl I saw in my head whose parents passed away in China or somewhere East, and she became the came the queen of her land at six or seven years old. The song goes back and forth between capturing the side of her and a narrator view. I do that just because I think that helps the form of the song, it helps the song lift off the page a little bit more. Not that it’s easier for me to compose, but I definitely have more tools to work with.

L+T: Is Penrose a fictional character or a real person?

AA: That’s a fictional character. It just sounds like an old-school southern Black name: Willie Penrose [laughs].

L+T: You mentioned Trayvon Martin as a source of inspiration. The song “Rollcall For Those Absent” is one that really sticks out and is very powerful. It’s simple but the circumstances speak for themselves.

AA: I feel like while I have this platform, I don’t want to just stand on the platform and yell “Me, Me, Me!” The role of an artist, like Maya Angelou says, is to liberate. My last album, I had “My Name Is Oscar” for Oscar Grant. The effect that that had was amazing. That made me realize what I’m here to do. Oscar Grant’s family started coming to my concerts; I would be in the Ukraine and somebody would come up to me and say, “Who’s Oscar Grant?”, and I would tell them the story. I said as long as I have this platform, I’m going to talk about stuff like this that relates to my fears, what I deal with. [A lot of the people named in the song] weren’t on national television, so that means just don’t know, even here America. So, I have a kid reading the names and then all of a sudden you hear “Trayvon Martin,” who’s known globally. It’s like a slap in the face, like, “Wait a minute? You’re telling me all these people are like Trayvon?” Then it comes again laid on top of Oscar Grant to tie it in and say the same thing happened three or four years ago and nothing has changed. I chose to have a kid read it because there’s something about the beginning of life talking about the end of life that’s really appealing to me. There’s a shock value to it and I really wanted to do that.

L+T: Grant is from Oakland and many of the others named in that song are from New York. You’ve spent time in both places. How has growing up in those urban settings influenced you?

AA: That’s a great question. Oakland is one of the richest cities in terms of culture in the world. The angle that I always think about when I meet people, they’re like, “Oh my God, you’re just so well-behaved.” That’s what it was when I was younger. “You’re just so different.” As I got older, I started to realize, I am that person standing on the corner selling drugs and hustling. I am these things, and the older I got, I didn’t want to separate myself from that. The more I wanted to say, “I’m the same cat that’s standing on the corner, so you might want to look at him a little differently too.” That’s what I think about a lot when I think about being from Oakland. A lot of my friends, they are those cats from the corners or that you read about in the newspaper. I always carry that with me. It gives me a lot of inspiration to represent for my neighborhood. I know that’s not really the question, but it’s what I think about daily, just trying to be a positive voice for my race, specifically my community and more specifically for Oakland. The Oscar Grant thing really hit home for me because it happened ten minutes away from where I grew up. You look at him and it’s like, “Man, that really could have been me.” I’m the type of person where I will speak up. Now that I’ve gotten a chance to know his family, [I found out] we had friends in common. It’s crazy.

the imagined savior is far easier to paint is available today.