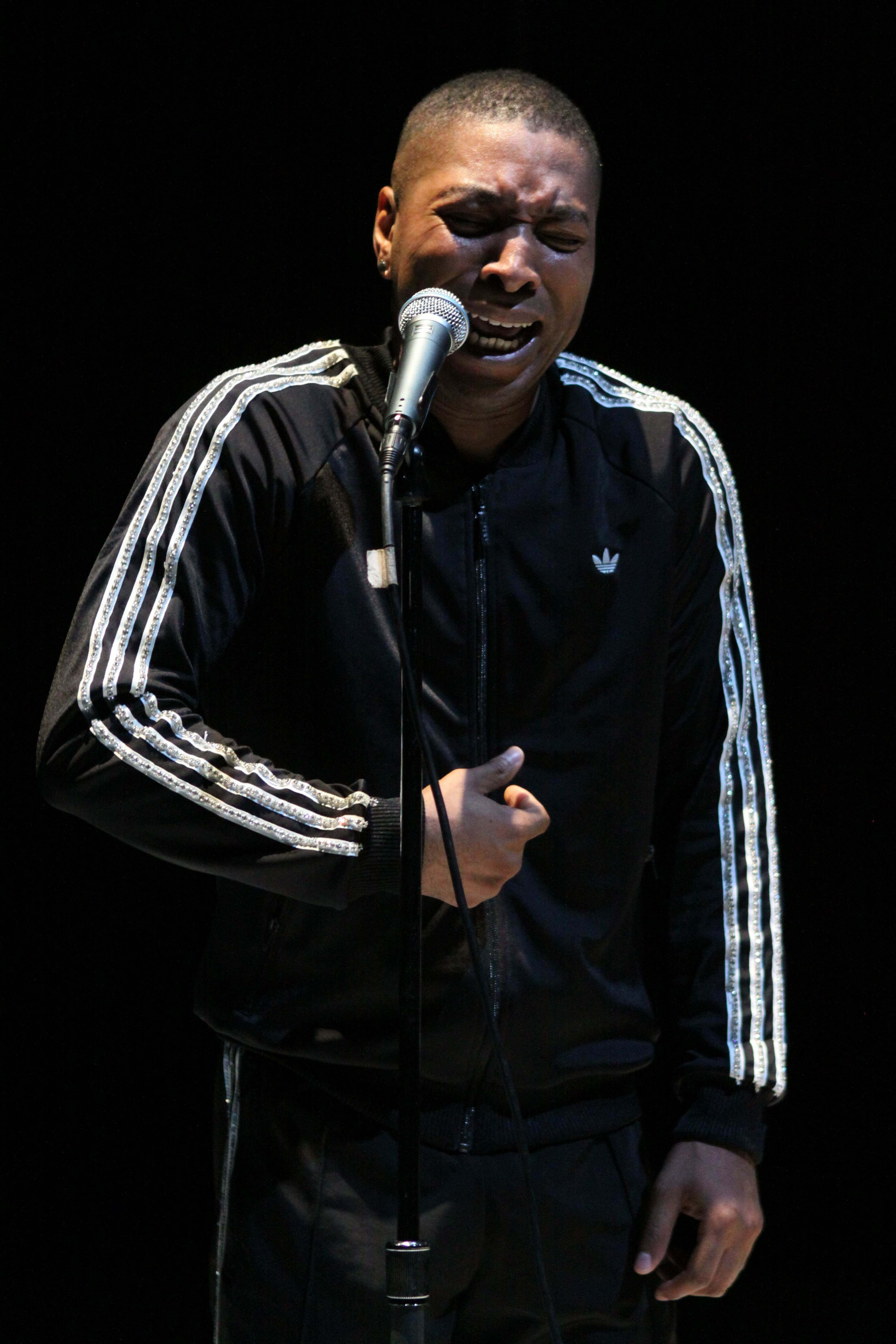

Choreographer Kyle Abraham Discusses “The Watershed” and “When The Wolves Came In”

01.12.2015

ART & DESIGN

Kyle Abraham’s latest two works, “The Watershed” and “When The Wolves Came In,” live up to every bit of his mission. “The mission of Kyle Abraham/Abraham.In.Motion is to create an evocative interdisciplinary body of work,” he says on his website. “Born into hip-hop culture in the late 1970s and grounded in Abraham’s artistic upbringing in classical cello, piano, and the visual arts, the goal of the movement is to delve into identity in relation to a personal history.”

Working from that foundation led Abraham to the position of New York Live Artists’ resident commissioned artist, where he collaborated with visual artist Glenn Ligon and musician Robert Glasper, and produced “The Watershed” and “When The Wolves Came In.” Similar to some of his previous work, pivotal, real-life events are the impetus. “The Watershed” derives inspiration from the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, the 1960s and Civil Rights; “When The Wolves Came In” grows from Emancipation, as well, in addition to the 20th anniversary of the abolishment of apartheid in South Africa.

Both pieces opened in late September and have runs through 2015. Life+Times talked with Abraham about his latest works and telling stories through movement.

Life+Times: Talk first about “The Wathershed” and the story that work is telling.

Kyle Abraham: “The Watershed” is a pretty abstract narrative. Both programs are really inspired by the same source material, they’re both looking at the Max Roach album, [We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite] and that album being a response to the100-year anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil Rights movement at that time. So when we get to “The Watershed”, where we make an evening-length dance – it’s a little over an hour – I was trying keep that in mind and also think about where we’re at right now. What are the gains and losses we’ve had? How are we viewing those gains and losses and what is the perspective on them, especially as Americans? It can be a tricky thing, but that’s where it’s coming from.

L+T: And then there’s “When The Wolves Came In”.

KA: That program is three works looking at that same source material but broken up in three totally different ways. The first work is actually called “When The Wolves Came In,” as well. It’s a work for seven dancers set to Nico Muhly’s “A Good Understanding” from the Los Angeles Master Chorale, so it has this kind of ceremonial vibe to it musically, but it’s speaking about perception, really. I was thinking about the story of these Africa dogs at the Pittsburgh zoo – Pittsburgh is my hometown so I still sometimes read the local news – and there was this story of this two-year old boy who fell into their pit in the zoo and the dogs mauled the boy to death. Instead of building a higher fence so that no one else could fall into it, they killed the dogs. It just brought up an interesting thing about perception, race and identity. Using that as a jumping off point that’s where I decided to go with that work. There’s a work called “Hallowed” which is a work for three dancers with a solo that opens it, set to these gospel hymns that were sung during the Civil Rights era. It’s a pretty haunting piece, super-specific in its movement and really idiosyncratic in how we’re thinking about the timing and focus with the dancers. The last dance in that program is “The Gettin’” which is in collaboration with Robert Glasper and the Robert Glasper Trio basically interpreting the Max Roach album.

L+T: How was it working with Robert Glasper and Glenn Ligon? How were they able to help you tell these stories?

KA: They’re both brilliant. Robert is a clown, man. He’s a real character and makes such an easy work environment. When he’s in the space, he has no qualms about letting you know he wants to have fun. It’s like, “Yes, we’re gonna work and we’re gonna work hard, but ultimately, is this is what we love to be doing, we should be having fun doing it.” He’s really in tune with Roach’s music and their family. He’s interested in the history of jazz but in a way that connects to both what he does and I do. We both come at the traditions in our field with our own history and identity born in the late 1970s and allow that to weave itself into the traditions of the genres that we’re working in. That was something that drove me to want to work with Robert, as well. With Glenn, I’ve been a big fan of him for years. I used to work in the visual art world at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh so I’ve been really in tune with what he’s doing. He’s such a brilliant person. When Glenn’s in the space with us, he’ll give me feedback or a historical reference on dance or the music I’m playing with. He has such a working knowledge of our history.

L+T: For both pieces, how are you trying to tell these stories in ways that make sense but aren’t too abstract for the audience? As the choreographer, how do you manage that challenge?

KA: Oh, man, that’s tough [laughs]. That’s the struggle of any performing artist, it’s a constant conversation. Things come up. [I’ve] talked to Bill T. Jones about this: when you put a Black body on the stage, there’s already an inherent story that’s going to be told. And when you put that Black body on stage with any other dancer, the story shifts based on the history that whoever is watching it has already experienced. Whatever your experience is – if you’re seeing a Black body and a white body, a Black man and a Black woman, and Black man and a white man – all of those things have their own kind of politic to them. The blessing and curse in that is how can we address the subject matter in new ways, but in ways that still bring an audience into the work in a way that they feel comfortable talking about it. In “The Watershed” there’s a scene two Black men are dancing together pretty intimately while a white man is sitting underneath a tree cutting a piece of watermelon with two Black women just sitting there. There’s a lot just in that. Even if they weren’t dancing and it was just the man cutting watermelon, it has its own tension.

L+T: You mentioned being born in the late 1970s. I imagine there aren’t many choreographers that have reached the level you have and come from your same background of being Black and growing up in the hip-hop era. What perspective are you able to bring to choreography?

KA: It’s an interesting time. Growing up in that early hip-hop time, when you went out and danced, there were moves and set up social dances, but you would just start dancing. That’s where my roots are, so when I’m creating dance, still today, a lot of the time I’m just moving in relation to what the subject matter is – the same way you’re thinking about whatever the song is. I think it created a different entry way for me into modern dance when I started studying. I didn’t do that until I was about 17, so I had spent many times in the club growing up. I think there’s a little bit of that and a little bit of this cross-culture thing that used to happen back in the early 80s when you’d watch MTV and it would go from a rap video to a rock video. That’s something that’s really in my work. I’m using a lot of different sources, but in a way that shows appreciation for all of them and it’s not rooted in just one thing. When I think hip-hop, especially earlier hip-hop, the samples were smart. When you think about BDP and what they were doing, the political messages in some of their tracks, the samples they were choosing to use, that’s really inherent for me in what I’m hoping to do with dance. It’s really drawing a line between history and a contemporary aesthetic, as well.

For more information about Kyle Abraham, “The Watershed” and “When The Wolves Came In” visit here.

Photo credit: Ian Douglas & Steven Schrelber