Author Jordan Ferguson Discusses New Book “J. Dilla’s Donuts”

05.07.2014

MUSIC

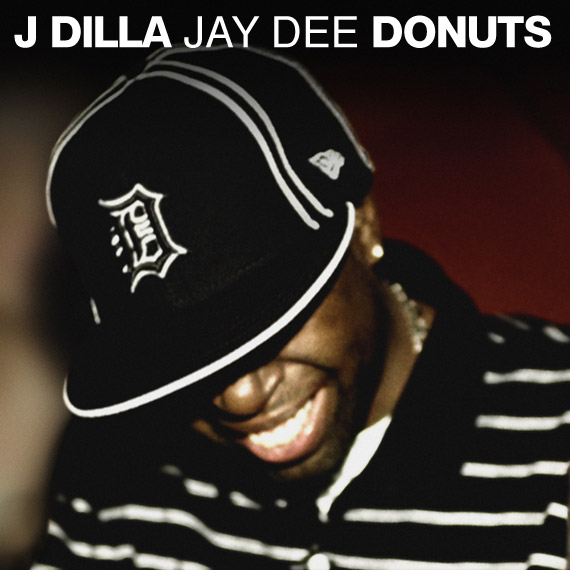

Creating timeless work is the primary goal of all artists, and something James Yancey (better known as J. Dilla or Jay Dee) did for much of his abbreviated, but meaningful life. The continued relevance of his work posthumously highlights that point even further. Author Jordan Ferguson takes a critical look at Dilla’s final body of work, Donuts – released February 7, 2006 on his 32nd birthday, three days before his death – in the latest in Bloomsbury Publishing’s “33 1/3” series, J. Dilla’s Donuts.

“At this point, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve listened to it,” says Ferguson. “People ask me am I sick of it and the funny thing is, I’m not. If anything, I love it more now than I did when I started the book, and this is after probably hundreds of listens. I still think it’s a genius work made more so by the fact of the conditions in which it was created, and if it adds to your appreciation that’s fantastic. That’s all I wanted out of this project: to do right by him, and give back a little bit of the enjoyment that he has brought to my life.”

Ferguson’s 130-page examination of the 32-song instrumental album goes much farther than rumors and interviews, delving into philosophical and musicological theories about death, dying and the role they play in Donuts’ aesthetic: why he chose certain samples and why the beats sound the way they do. In addition, he provides a sound biography of Dilla growing up in Detroit, becoming a producer and evolving over time, talking with many who knew and encountered over the course of his life. Life+Times spoke with Ferguson about the legendary producer and his final opus.

Life+Times: What was your initial reaction to Donuts, and at what point did you decide that it was something that could be studied more critically than the average album?

Jordan Ferguson: When I first encountered Donuts, I had kind of been off hip-hop for a while. I grew up loving it, I grew up in a border town directly across from Detroit, so I was exposed to it on the playgrounds at a very young age and loved it. By the time the rock resurgence of the ‘90s hit, I kind of stopped paying attention. I knew Jay Dee before I knew J. Dilla, so much so that when I first encountered Donuts, I didn’t know that he had passed until I was reading one of the Detroit papers the week he had passed and there was a cover story on him. That’s when I realized: A.) that he had passed and B.) that it was the same guy that did all the beats I liked – the few things that made it through to me when I was avoiding hip-hop in the ‘90s like “Runnin’” by The Pharcyde, Common’s Like Water For Chocolate. The funny story is, I was working at a small paper at the time, and we had a review copy of Donuts. I recognized the title when I saw it in the article, so I went and stole it from the Arts office, put it in to listen, and I hated it. I did not like it the first time I heard it because I was not prepared for it. I was expecting what I knew, expecting to hear Q-Tip, A Tribe Called Quest stuff, and you get these very quick, mashed beats. Everything I did like was over in 30 seconds. It was years later – I don’t know what prompted me to go back, but I guess I just needed six years to catch up to where he was. I didn’t go to it cold, I had heard some of the online theories about how the samples were messages. When I went back, I probably had that in mind and heard something different in it and appreciated it more as a whole piece of work, I wasn’t looking at it as individual songs, I view Donuts now as one 45-minute work, not 32 different songs. It wasn’t my first instinct to go with Donuts as the topic for the book, I thought it would be too hard to do an instrumental album. I didn’t want to just rehash what people had been saying on the internet for years. When I started thinking more, Dilla was a guy who could find the best part of any record and make something beautiful and amazing out of it. At the end of his life, he was making these strange, loud, abrasive beats with source material that could have made something far more traditional. He could have taken all those records and made something that sounded much more traditional and contemporary, but he didn’t. I was interested in, “Why does Donuts sound the way it does?” If we’re going to accept that this music is about death and dying, why did he pick this music?

L+T: After going back to Donuts and it taking on a greater meaning, talk about the process of doing the research and finding the people to interview for the book.

JF: Initially, from the research standpoint, I wanted to really dig in to the samples. Not just hopping on the internet and doing a quick search, but who was involved in the production of the samples. Interestingly enough, some of the samples that he used had also been used in popular records at that time. He uses the same sample as “Hate It Or Love It” by The Game; there was an Usher song [“Throwback”] that Just Blaze produced that used the same Dione Warwick sample he used for “Stop!” When I noticed that, [I thought,] “Ok, he’s listening to things that are out there.” He didn’t do anything by chance. He didn’t have the luxury given his health, and he had a reputation for having the beat done in his head before he even started. Numerous people have said that they’ve seen him in record stores in Detroit listening to something, taking the headphones off and bobbing his head, and having the beat done mentally before even sitting down at the equipment. Also in mind was that he had limited time and that he probably knew it. If the album is about death and dying, I started wondering about what that means if you’re in that position. From a research standpoint, that led to, “How do we process as people the fact of our own mortality?” Looking at the Kübler-Ross [Five Stages of Grief] theory, I just started making charts of, “If you were to look at the samples, the messages that are in there, the titles that he used, vocal snippets sprinkled throughout, could you place these songs on a grid of the Kübler-Ross model? If this is actually about death and dying, could you process that fact through his music?” That was a thread I started pulling at. I’m not here to say my ideas are right or wrong, but I do think there is something there. There are songs on that album that pertain to every stage of that Kübler-Ross model. Additionally, when I was drafting the book pitch, I came across this book On Late Style: Music and Literature Against The Grain, by the critic Edward Said. He looked mostly at film and literature with the idea that when an artist is facing the end of their life, their work seems to either turn into a creative summation – “this is everything I have to say about life” – or they go in the other direction, where it’s like, “I have nothing left to lose, I’m gonna make the weirdest, craziest stuff.” When I looked at the book and the language they were using, I could apply them to Donuts and it would make sense. Musically, it sounds like nothing he ever did and the adjectives they use, words like “fragmentary,” “confrontational,” irascible,” I believe you can apply wholesale to Donuts. As far as reaching out to people, I hoped that because people feel so strongly about him and his work and are really protective of it, that they’ll be more than happy to help. What ended up happening was I [rarely], with few exceptions, had to reach out to anyone. People came to me once the word got out, the guys at Stones Throw, House Shoes, Peanut Butter Wolf, all these people have been fantastic. I looked at my job both as trying to find new information and get stories from the people who were there, as well as to try and form a narrative from all the material that’s been floating around for 20 years.

L+T: You reference Joseph G. Schloss’ Making Beats: The Art Of Sample Based Hip-Hop and his six commandments of producing. As you point out, J. Dilla didn’t follow any of them, he played by his own rules.

JF: I was really fascinated by the [Black Star] “Little Brother” story, which I had heard long before I started writing the book. How he essentially made, arguably, one of the most insane flips ever for practice, something he had no intention of ever releasing, out of respect for Pete Rock. That led me to start thinking about these ideas about “the codes.” As a kid, you always heard that biting was a cardinal sin growing up as a fan of ‘80s hip-hop. Biting was terrible, you just didn’t do it. I came across Schloss’ book more interested in making sure I got my facts straight no the history of production. If I wanted to make an argument for why Dilla was so great, I had to go back and fill in the blanks for people who might not know how that art form developed. Schloss has a chapter in there on producer’s ethics, which includes “only use vinyl,” “no biting,” etc. When I was reading those, it occurred to me that Dilla didn’t care about any of this stuff. On Donuts, there’s two or three samples – he uses “Long Red” by Mountain, that’s a classic break, a Pete Rock trademark, been used a million times; he uses “UFO” by ESG on there. These are staples. It’s fascinating to me that he didn’t care. What’s more, others didn’t care that he didn’t care. He never did it lazily. He was never going to go to one of these classic samples – a sample that could be considered “biting” – and do it straight. He was going to put his stamp on it. That runs throughout his life. These practice beats – I know there’s “Pete Rock batches” where he would try to learn and do things in the style of Pete Rock. Questlove has said, to his mind, those 2005-era batches that the Donuts beats came from, were kind of the Kanye and Just Blaze batches, where he uses soul samples which had a resurgence in the post- The Blueprint era. He would always look at what was happening then try to put his own spin on it trying to make it his own. His nonchalance toward the rules ran both ways. One story I heard that I didn’t put in the book was that he was in LA and Dilated Peoples’ “This Way,” produced by Kanye, was premiering on the radio. The song starts and Dilla spots his drums from “Fuck The Police.” Not even the same sample, he’s just like, “Those are my drums.” And he didn’t care. If it made good music, he didn’t care what anybody did to make it. If it was dope, it was dope, and that was always his philosophy towards it. He would sample from everything.

L+T: Looking at previous work and talking to people on your own, what was the common thread as people discussed J. Dilla?

JF: The one thing people always came back to with him was the dedication. He did not care about being out in front of the camera. He produced all these beats and people would make videos, but you never saw him in the videos. He wasn’t about that. Wajeed tells a story about how he and Dilla would leave voicemail messages for each other all the time at 3, 4, 5 in the morning because they’d always be up making beats. Wajeed says he misses those voicemails because it reminded him of when people would want to go out to the club or party, that he needed to be in the basement making beats. One thing Madlib said after he died was that he doesn’t listen to anyone complain anymore, he doesn’t have time for it. Because with everything Dilla was dealing with, he rarely complained and he was always working. You can’t overstate how insane his work ethic was. I heard over and over again from people how dedicated he was to his craft. His mom, Ma Dukes, tells a story where neighbors would mention seeing Dilla in magazines or newspapers, and she had no idea because he never mentioned it. They talk about the 10,000 hours that you have to put in to be a genius and he had to put in well over those 10,000 hours.

J. Dilla’s Donuts by Jordan Ferguson is available here.