Black On Both Sides

01.04.2012

LEISURE

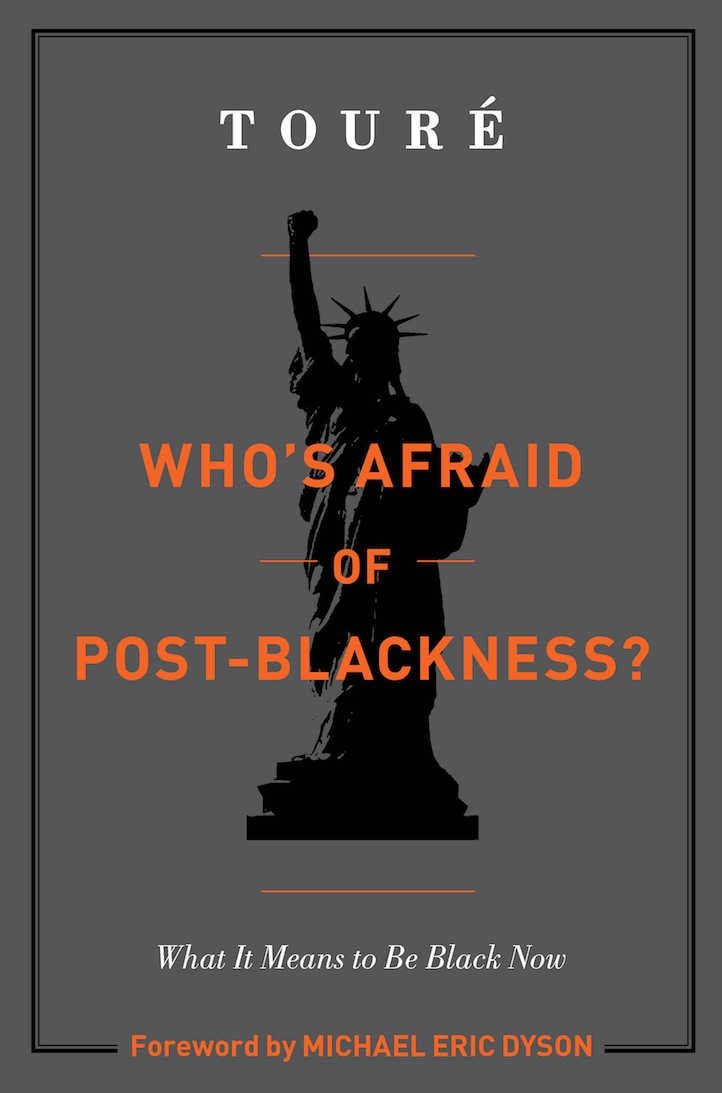

Toure‘s new book Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness is meant to be provocative. He interviews 105 prominent African-Americans in an effort to expand a conversation about identity politics and what it means to be Black in the age of Obama. The book is limited to African-Americans where it could have included the diaspora, but he does speak to a wide range of thinkers, from Dave Chappelle, whose show Toure regards a cultural marker in the 21st century shift of the way race is discussed, to Kara Walker, the famous artist whose work has always invoked riotous conversations about slavery. Scholars like Michael Eric Dyson, Henry Louis Gates, Blair Murphy Kelley and inaugural poet Elizabeth Alexander are given space to unpack their ideas. In the book Toure is careful to distinguish “post-Blackness” from what he calls the meaningless “post-racial.” Here we talk book reviews, skydiving and Nazis.

Life+Times: You’ve really been making the rounds. Your new book is a conversation starter. Talk to me about how you’ve experienced its reception.

Toure: It’s made The New York Times‘ and The Washington Post‘s “100 Most Notable Books of The Year” lists and I’ve gotten incredible reviews so mostly it’s been gratifying. I also love when I’m walking down the street and I encounter people who thank me, who tell me they needed this book when they were a kid, that they needed to hear this message, that they feel pulled back in. Then there are detractors who fall into several categories: [Those who have] not read the book they reject it because they don’t like the concept. People who don’t like me or the fact that I’ve married outside of the Black-American community (my wife is a Lebanese-American) and are like ‘How dare you try and speak for us’ or, people who’ve read it and disagree and have informed and legitimate counterpoints.

L+T: Are identity politics dead?

Toure: No, they’re still very important. To be Black or Italian or Jewish or gay matters, not only to who you are but how you experience the world. So I wouldn’t say dead. But what I was trying to do is get people to see a broad potential for identity, that it could be performed in a variety of ways. I want to graduate from legitimacy or authenticity arguments or essentialist way of reducing Black identity.

L+T: I know you’ve done it other places, but please define for me what you mean by “Post-Blackness.”

Toure: It’s being rooted in but not constrained by Blackness. We want to be Black. We want to be grounded in Blackness. Blackness shapes us, and will and should continue to shape us but at the same time there’s a buffet of things you can do or be that don’t have anything to do with “being Black” and I wanted to look at those things. The skydiving example is one that sums it up in the book. It was an example where I was told “Black people don’t do this.”

L+T: Most people don’t skydive. It’s a forfeiture of your life insurance policy.

Toure: Absolutely. But skydiving changed me, and my relationship with God. It cemented my certainty that there must be a God. I wasn’t an atheist before I went, but I was convinced of God when I skydived. What if I hadn’t gone because I believed skydiving was simply something Black men don’t do? Then I would’ve missed out on an experience that helped me grow as a human. The experience that I had and the way it made me grow made me want to go home and attend a Baptist church service in Brooklyn.

L+T: What inspired you to expound upon Thelma Golden and Glenn Ligon‘s term “post Blackness”?

Toure: In the catalog for the show Fresstyle, which Thelma Golden curated for the Studio Museum of Harlem, she wrote about her and Glenn Ligon searching for a way to talk about art that had evolved from what we’d typically considered “Black art.” In 1989 Trey Ellis‘ New Black Aesthetic was published and be began a conversation about “cultural mulattoes,” so I wasn’t the only one noticing it, this nuanced shift in Black identity politics. The argument was being made that the potential for identity freedom is infinite. There are a million ways to be Black.

L+T: Some people simply don’t have access to that freedom.

Toure: That’s true. It’s very easy to say working class or people in jail don’t have access to that freedom. But it’s also too simplistic to say only middle class people can sit around and philosophize about who they are. We know there are many working class people who are coming up with their own philosophies. It’s kind of like with white privilege. Not all white people have access to white privilege, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

L+T: What about the idea of exploring Post-whiteness?

Toure: The way we interact with Blackness and they way they interact with whiteness are not equal. It informs and restricts our lives the way it informs and restricts Jewish peoples’ lives or homosexuals’ lives. Whiteness doesn’t constrict their lives. White people have always been able to do what they want to do and not to be held back by whiteness. It’s not equivalent to the impact Blackness has had in our lives.

L+T: What about our culture is restrictive?

Toure: In previous generations, there was a sense of movement, an army that we were in – we were marching forward for democracy, it was a struggle that was tangible. Within that movement it was valuable, maybe even necessary, to have a cohesiveness to the way we were moving together in a certain direction as Black people. Our generation doesn’t have the same restrictions, we can get into schools, we can get the bank loans, move where and how we want.

L+T: Well that’s certainly not true, not in a wide way. Education, housing, even the recent subprime scandal, are all grossly informed by race.

Toure: I’m not espousing something, I’m reporting something that already exists, I know that there are large numbers of Black people who are not benefiting from these new freedoms. Many people aren’t feeling the benefits of it. A lot of white people could say “This doesn’t feel like a free or prosperous country for me,” too. Fair enough, I can’t change that for you. The nature of racism has morphed. We still have institutional racism but we have a more amorphous racism that’s harder to see. And it’s a fact that a lot of the ways we interact with Blackness is different than our grandparents’ and we’re seeing that shift happen in our lifetime. We don’t have total freedom but we have far more opportunities than our parents and grandparents did.

L+T: In your book you ask people what was the most racist thing that every happened to them. Everyone had an answer to that question. Did anyone’s answer surprise you?

Toure: Everyone was ready with a story! No one had to reach too far back in their memory. This is luggage that sits by the door for us, whether it’s 10 or 20 years ago. The stories people shared with me were massively impactful; the answers were often tied to who people became. These were seminal events in peoples’ lives. None of the stories surprised me, we share these stories amongst each other, we’re familiar with these stories. But I was grateful for people’s honesty, in some cases they were telling me stories their families didn’t want repeated. Jesse Jackson‘s story about his grandfather being a Black soldier in World War II Germany and having less rights on the army base than the Nazi POWs seemed so incomprehensible that it was like an exaggeration. The most immoral people of the last century got more respect than Black soldiers who were risking their lives for freedom? Then [former New York City mayor] David Dinkins spontaneously told me the same exact story.