Visual Artist Robin Rhode Speaks On South Africa Exhibit

04.15.2013

ART & DESIGN

Robin Rhode is a South African born artist who lives and works in Berlin. His work has been exhibited at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Haus der Kunst, and The Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio. Rhode returned to South Africa for his first solo exhibition in fifteen years at the Stevenson Gallery, which opened on April 11th. Life + Times spoke to Rhode about his new work, his return to South Africa and drawing on the walls.

Life+Times: You were born in 1976 in Cape Town and raised in Johannesburg. How does your background shape you as an artist?

Robin Rhode: As an artist one’s background becomes the core element in shaping one’s view of the world. Growing up in Johannesburg does allow for a very specific cultural background that was shaped by the political turmoil of the past. However, it is the youth generation, the post-apartheid kids, who have a new perception of the future without having to carry the baggage of history. Only through understanding our past will we be able to shape the cultural landscape of the future, no matter how peripheral one could appear to be.

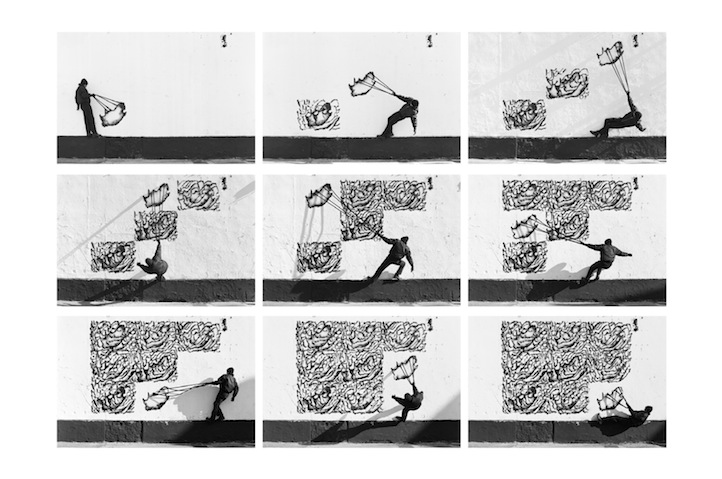

L+T: You’ve said ever since high school you’ve been drawing on walls (the translation for Paries Pictus). Why did you start? What influenced you to make public art?

RR: I started making art as a necessity to express myself. Walls were the best surfaces to deal with ideas and scenarios that were proportioned on a human scale. My work could then incorporate the audience, the general public, into the idea, or drawing field, as I tend to refer to it. My motivation when I started was to communicate contemporary ideas to a public who had limited access to visual arts, museums. The accessibility to walls within the public realm allowed me to communicate directly to this particular audience. The reaction by the general public allowed my ideas to become transcendental, which is what I believe great art should be.

L+T: Will we see distinct South African imagery in your new work?

RR: There is a remarkably strong South African distinction in my current body of work. From the re-occurring image of the knife called “Ou Kapi” used by street gangs across South Africa, or the work titled “Twilight” which takes it’s inspiration from my dialogue with the acclaimed South African poet Don Mattera, who describes the physical and mental state of people who exist on the periphery, either through economics or race, as occupying areas of twilight, between black and white, light and dark, between knowing and not knowing. These are very specific South African themes on identity that is inherent in my current body of work.

L+T: You tackle the subject of cities, community and multiculturalism. How do your ideas take on a global context as you continue to travel for shows and installations?

RR: Through travelling abroad one begins to realize how relational these issues really are. Art allows us to engage with these issues from a more globalized perspective. It takes people from other societies to create artistic interventions that allow us to understand our time and place with greater clarity. It’s through this process of interaction that we begin to understand that rationality, contribution, and concern are the mechanisms required in sustaining notions of a shared global community.

L+T: You are identified as a South African artist, but your studio is based in Berlin, where the art scene is percolating. Why Berlin?

RR: I travelled to Berlin in 2001; it’s here that I fell in love with a beautiful woman. Then only did I fall in love with the city. In winter my love for the city turns to hate. I have no real contact to the art scene in Berlin. But yes I have heard that it is a thriving art scene even though I prefer to sit and look from a distance. Voyeurism at times is a lot more interesting than participating in the scene itself.

L+T: Paries Pictus first appeared in Turin two years ago and is currently on view in New York. How will the exhibition changed in your native South Africa. How does the community based aspect of the project change the dialogue?

RR: In South Africa I’ve included new wall drawing activities, these wall drawing interactions have an interesting relation to notions of the city, even notions of colonialism, but all produced in a very reductive way to make the ideas accessible and as youth-orientated as possible. The community definitely places the wall drawing activities into a very specific context that also mirrors their thoughts, ideas, and feelings. All these elements create a perfect scenario for coloring-in pictures and connecting dots.

L+T: What did you learn from the children who’ve participated in the realization of this work? How do objects take on perceived meaning in your work?

RR: I’ve learnt that children have a particular liking to objects, images, that relate to their personal lives. My work has incorporated children before and my interest in youth stems from the innocence and purity of their imagination. In the wall drawing activities of Paries Pictus I’ve used images of houses, flowers, urban cities, communities, which have excited the majority of kids who’ve participated. The inherent meaning of these objects originates from the reflection of their own lives and experiences they see within these objects, similar to what adults experience when viewing works of art in galleries and museums. Only in this case the children are able to shape the imagery through layers colors and mark-making.

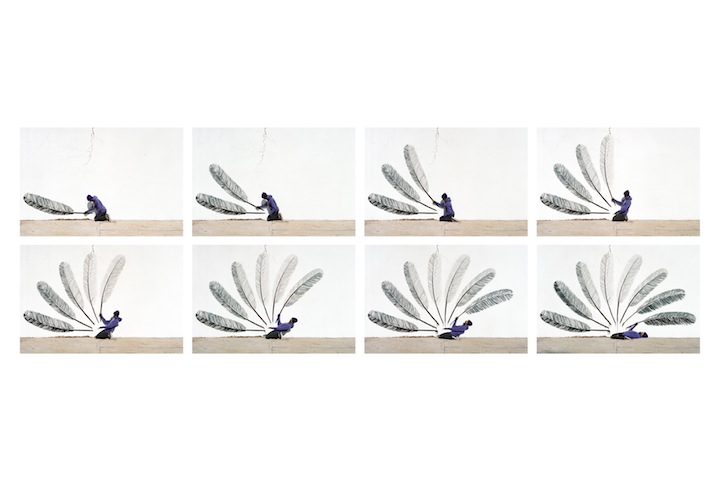

L+T: You physically participate in the work itself. What’s your process like for making a new body of photographs?

RR: I tend to build a body of reference points for the work, either as inspiration for the physical action, performance, or for the wall painting. These references could vary from images gathered from newspapers, the internet, or even existing art, mathematics textbooks, or visual journals from various subject matter. I try to visualize my idea by constructing a visual vocabulary. Once my idea is set, I then begin to work on the painting process. This can vary from using spray paint to basic wall paint, from freehand painting to stencil use. I try to establish all of these processes beforehand. During the period of constructing the visual vocabulary I will scout for walls in the given city. If I’m unable to find a perfect wall for the creation of the artwork I make plans to return to Johannesburg to work there instead. This tends to happen quite frequently since when working in an exterior setting I do find the cold winters of certain cities unforgiving. Probably the most important element in the process would be the wall and it’s location. So much depends on its scale, surface, amount of daylight it receives. A secure environment is also a priority, especially from the eyes of the police.

L+T: What are your next projects?

RR: My studio Rhodeworks also moonlights as a music producer of limited edition vinyl records and we have a few interesting albums lined up by musicians from various genres. My studio places massive emphasis on the aesthetic of each vinyl record and album cover so that the music becomes almost sculptural. The upcoming limited edition vinyls include underground hip-hop instrumental beats from the group Sky Klinic in Johannesburg, an Afro-German electronic jazz album titled From Bamako to Abidjan by Edward Maclean‘s Adoqué, followed by a noise album by the experimental noise collective from Lake Michigan called Ching Suru. Whether it’s music or wall painting, they each possess rhythm.

Credits On The Next Page