Jenny Sabin: Art, Architecture, Design and Science

10.01.2012

ART & DESIGN

How do you knit and braid a building? Could a building be as lightweight as air? How can sport influence both design and fabrication and inspire the next generation of buildings? What if we could form-fit and enhance architecture with bio-architecture and performance of our own bodies? Turning performance into structure for the Nike Flyknit Collective, Jenny Sabin is an innovator who works at the intersection of art, architecture, design and science. There are instant similarities in her approach to the work of Nike’s Innovation Kitchen, where disciplines from different fields are brought together with a view to re-thinking basic principles and approaches to design challenges. Here, Sabin breaks down her collaborative experience exclusively for Life+Times.

Life+Times: Before we get into it, can you tell Life+Times a little bit about who you are and what it is that you do?

Jenny Sabin: I am an educator, researcher and architectural designer. I am an Assistant Professor of Architecture in the area of Design and Emerging Technologies in the Department of Architecture at Cornell University. I also direct a lab where I collaborate with material scientists, cell biologists, engineers and mathematicians on funded research where we develop, analyze and abstract dynamic systems through the generation and design of new tools. These new approaches for modeling complexity and visualizing large datasets are subsequently applied to both architectural and scientific research. I am also Principal of Jenny Sabin Studio based in Philadelphia where I apply many of these ideas towards built projects from installations to pavilions. I work at the intersection of architecture, art and science and am interested in the unseen structures, qualities and beauty inherent to data, specifically data from the human body. My work is often inspired by biology, whose systems are newly revealed with experiments in material construction, fabrication and digital techniques. Frequently, topics such as sustainability are addressed in technical or statistical terms only. I’m interested in re-thinking the entire conceptual project around such topics and mining the body for biodynamic models that may afford new ways of approaching issues of performance and adaptation in architecture.

L+T: With this project, you’ve turned performance into structure for the Nike Flyknit Collective. Can you tell me a little bit about this project?

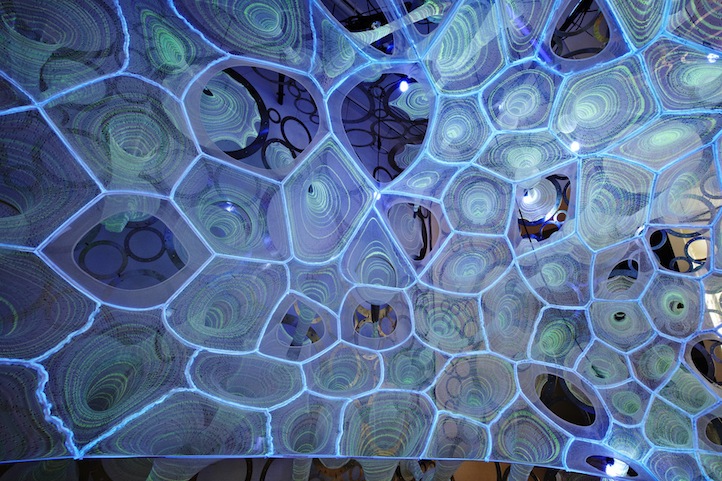

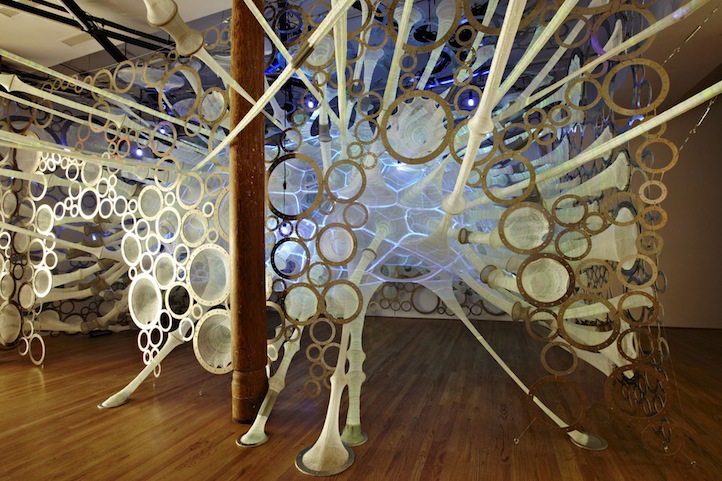

JS: The starting point for my project with the Nike Flyknit Collective was to bridge the complexity of the human body in motion with the simplicity of knitting. More specifically, I was interested in probing how sport could influence architecture. Some of the big questions that I had are: What if you could knit, weave and braid buildings? What if you could personalize and enhance architecture with the bio-architecture and performance of our own bodies? How might sport influence next generation buildings? Ultimately, the myThread Pavilion is a paradigm shift in soft textile-based architectures. myThread integrates data from the human body with lightweight, high performing, formfitting and sustainable materials. The myThread Pavilion uses the flexibility and sensitivity of the human body as a biodynamic model for pioneering pavilion forms. myThread features novel formal expressions that adapt to changes in the environment and increase building performance through formfitting and lightweight structures.

L+T: It’s been said that you often start from a molecular point of view, where the singularity of a single unit such as a zip-tie becomes the building block for structures of great complexity. How does this relate to your collaboration with Nike?

JS: I’m very interested in the topic of personalized architecture and how our very own bodies may inspire new models for negotiating pressing topics such as building performance and sustainability. Beyond these practical concerns, I’m interested in how architectural form may materialize and visualize that which is intangible. We live in an increasingly data-centric world. I’m interested in probing how architecture may provide an interface for making this paradigm meaningful, playful and fun and ultimately put the role of the human being first.

L+T: The body, or more specifically the body in motion — pure performance itself — is the starting point of your collaboration. How so?

JS: I start by mining the human body for biodynamic models that may provide insight into practical issues such as sustainability and performance in architecture. The material and structural translations, such as those revealed in the myThread Pavilion, exhibit the unseen beauty inherent to these natural systems. I think beauty and play are very important topics that impact practical concerns when it comes to translation. During the first NYC Nike FlyKnit Collective workshop, we outfitted participants with Nike Fuel bands and various devices to collect and capture data, human motion data to be exact. This data was then used as a point of departure in the design of the myThread pavilion. The pavilion is literally generated by human data in combination with material constraints inherent to knit geometry and patterning. What better than to turn to humans for next generation models in architecture? The results are not only intriguing and beautiful, but inspire new approaches to building structure and performance. The large-scale architecture reflects a collective and dynamic body of data.

L+T: When putting together this installation, how did you educate yourself and utilize Nike Flyknit technology in order to help conceptualize your vision?

JS: Spending time with Ben Shaffer, Nike Innovation Lead, and his team at the Nike Beaverton world headquarters was a big highlight. They have labs and creative studios similar to what I engage in, but with altogether different directives and resources. I had not had the opportunity to work with a cutting edge corporation and industry before the FlyKnit Collective. It’s been a hugely positive experience in that regard. It’s really fascinating to see how they conduct research and turn it into reality. The second aspect of the FlyKnit Collective that I really enjoyed was working with the diverse groups of participants during the summer workshops in NYC. I had never had to organize such a diverse workshop brief before for both extreme athletes, artists, scientists and designers! There were some great workshop results and experiences because of this fantastic mix.

L+T: What was the process like setting up this installation? Can you give me a little bit of background into getting the actual pieces set up?

JS: The first part of the construction sequence entailed arranging and connecting the aluminum laser cut rings into the designated packed configuration that you now see in each exterior panel. When one panel was complete, we rigged it up and installed it within the Nike Stadium in NYC. The placement of the rings nets was the first step. Once the exterior frame of ring nets was complete, we began linking each individual knitted element to its designated exterior ring location. Everything was carefully designed ahead of time, including testing and simulating the tension forces at each knit element. As the knit elements were placed, the soft-textile interior form slowly took shape. The entire fabric structure takes its form by being pulled into tension. In fact, when it arrived, it weighed less than 150 pounds! It had been carefully transported from the finishing factory in New Jersey to Nike Stadium by one of my team members in a single canvas bag! This is one amazing aspect of working with textiles and fabric architecture. The surface area is quite expansive in its erected state, but is equally transportable and compact. Once everything was in place, the bottom edge of the knit structure pulled into perfect tension like an inverted basket structure. It was all very exciting! Despite all of the simulation and design work ahead time, there was still a certain amount of form-finding to do on site. The minimal surfaces of the knit elements pulled and morphed into the amazing shapes that you now see and interact with. The material is very dynamic at all scales and that is the point! We started with dynamic data from the body and the pavilion itself is dynamic, from its structure to the material and surface effects. The entire installation took 10 full days with a team of nearly 10 people.