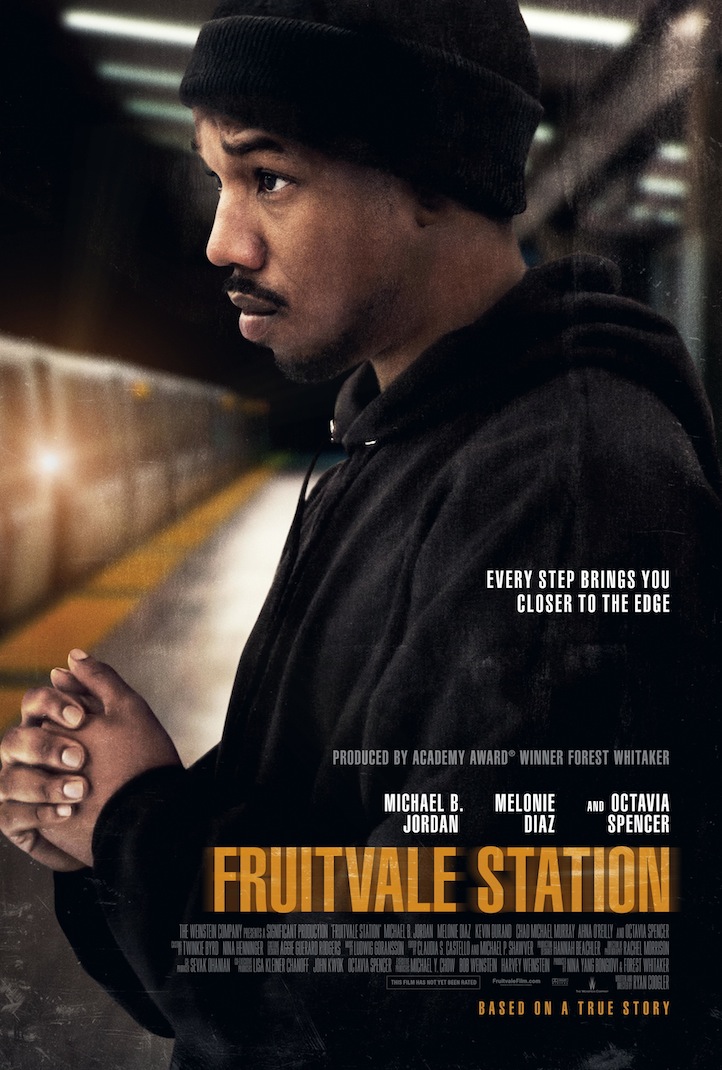

Director Ryan Coogler Discusses His Debut Film, “Fruitvale Station”

07.16.2013

LEISURE

Arriving directly on the heels of the recent Trayvon Martin verdict, Ryan Coogler‘s directorial debut, Fruitvale Station, based on the 2008 murder of unarmed 22-year-old Oscar Grant, could not be landing at a more relevant time. Since premiering at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, Coogler’s film has received rave reviews. Clocking in at 90 minutes, Fruitvale provides a thorough perspective on who Oscar Grant was as a person, giving some much-needed humanity to the situation. Life+Times caught up with Coogler – who’s from the Bay Area where the incident happened – to discuss Fruitvale Station.

Life+Times: What were your thoughts when you first heard about the Oscar Grant incident in Oakland?

Ryan Coogler: I was actually in the Bay Area when it happened, I was home from film school and I heard about what happened at the BART station from one of my friends who was on the train [coming] back from San Francisco that night. He didn’t really know what happened, he just heard someone had gotten shot, and it was holding up the transfer. Over the next couple days, details came out and the footage started to come out. We saw it on the news, on the Internet. I was shocked when I first saw it. You know you feel sick seeing someone get shot like that. The first thing that was going through my mind was I saw myself in Oscar. He looked like me. We were the same age. I’m from the East Bay, so we wore the same type of clothes, and his friends looked like my friends. So to see that happen, I really just imagined it happening to myself or one of my friends and how tragic that would be to not make it home to your loved ones unnecessarily, to have your life cut short unnecessarily. With the fallout from the case, as it got more publicized and people took the streets protesting and rioting, the news coverage of the trial with the officer, I think who Oscar was as a person got snatched in two different directions to the point that he wasn’t a human being anymore. To the point that he was either all one way or all the other way depending on what somebody’s perspective was. I was very interested in the perspective of the people that were closest to the incident, the people that knew him and loved him the most, that he was a full human being to with plusses and minuses. Not all good or all bad – he was a 22-year-old dude who was struggling to figure his life out, you know. So that’s why I wanted to make the film. To me, it was kind of a reminder of how often young African-American males have their lives cut short by gun violence. It’s a situation where you’re not safe. You’re not safe with the people from your neighborhood that look like you, you’re not safe with the people that are supposed to be protecting the neighborhood. You’re not looked at as a human being by any of them.

L+T: What were the steps that you took to bring the film to life?

RC: The first step I took was just thinking about it. I told one of my buddies in passing that wanted to do it. He happened to be from Oakland, as well, he was down at USC with me. He was at law school and I was at film school. He ended up graduating and going back up to the Bay to work for the lawyers that worked on the civil case. He had reached back out to me and said, “Hey, we’re wrapping up the case, I’m in charge of logging the video footage, can you help me with that? I also want to introduce you to [attorney] John Burris because that would be the first step if you wanted to make a film based on this.” So, I went and met with John Burris, showed him some of my short films and he said once the time is right for the family he would introduce me to them. In the meantime, I got recommended to Forest Whitaker’s production company by one of my professors and I went and met with them during my last year of school, and told them about some of the projects I was been working on – I told them about this project, in particular, how important it was to me and close to my heart. Forest was right there in the room and he wanted to help out with his production company. So from there, I was able to start working on the film using available documents about the case. I started tracking the trial and wrote an initial script based on that. In the meantime, I met his family, presented why I wanted to make the film to them and why I thought a film could provide some healing to the situation. They went from there – I was young, I didn’t have any feature films but they watched my footage and found out that Forest Whitaker was backing the production; from there, they came to Forest and signed over the life rights to his production company. Once they did that, I had access to his family, I had access to people that knew him the best. That research right there helped pave the way to weave more into the script. I was also supported by the Sundance feature film program, Sundance labs and the San Francisco Film Society. Those two non-profits involved in the film-making got us financial feedback. So from there, I was able to get going.

L+T: What has the response to the film been from his family and the general public? Was there any resistance from people that might not have wanted to you tell this story like this?

RC: To be honest, the Bay Area was supportive. If you look at it on paper, the people who would be most likely to resist the film would be BART, and BART was incredibly supportive of the film. They opened up their facilities to let us film there in the actual station where it happened, and on the train where it happened. The people in the community opened up their homes and businesses to let us shoot. We didn’t have a lot of money but people were super-supportive of the project. The response from his family – they saw it for the first time when it world-premiered at Sundance – it’s a difficult film for them to watch. It shows things they actually struggled, it shows their loved one brutally murdered. They were there for the real thing, so by them watching that, they had to re-live some of that. But they were very positive in what they said about the film and the performances of the actors that are playing the characters that they know and love. So, on that side of it, it was good. To me, it’s always as big as wherever the film plays because it gets people thinking and talking about these things. Some people didn’t know about what happened to Oscar. Therefore, just by watching the film awareness is raised and I think it makes people think about humanity and relationships. What I thought was that in making the film, people would be able to see themselves. Whether somebody is Black, White, Hispanic, Asian-American, they know what it’s like to be 22, to be young and struggling and trying to figure out your life. People know what it’s like to have a mom, a girlfriend, have lives that you’re responsible for, people that you mean the world to.

L+T: Talk about the job Michael B. Jordan did playing the role of Oscar and how you selected him.

RC: I was familiar with Michael B. Jordan through his work, he’s an incredible professional. Mike’s a young guy to be active for over a decade. In all of his work, he’s always been exceptional and when I was writing the script, I knew that we would need an exceptional talent to play this role of Oscar because it’s a really dynamic role. The guy’s on-screen for the entire film. So, I wrote the script with Michael in mind and I presented it to him. I didn’t know him, but a few things enabled us to make the connection. I think Mike just knocked it out of the park. He’s phenomenally talented and a great person, and he’s an incredible professional with an amazing work ethic. All of those things come through in his work, I think. I would have been lost without him on this project.

L+T: Talk about the importance of telling this story so soon after it’s happened, and you – a Black man who is very close to the situation – being the one to tell it.

RC: To be honest with you, it’s really hard to get movies made. It’s getting easier with technology and budgets, but it’s very rare that a minority gets to make the films. And I think filmmaking is really the most commercial storytelling form, and it has an incredible power to provide perspective. A lot of my favorite films are about communities and places that I didn’t have access to in my life. Oftentimes, they were made by filmmakers that did have access to them and held a very close perspective. You look at a film like Mean Streets by Martin Scorcese, he’s a guy from Little Italy that made a film that was personal to him when he was young about guys that he knew and grew up with. When I watch that film 20 or 30 years later, I feel like I had access to something that I never would have had access to because of that. So, filmmaking is one of those things that provides the avenues to have a human connection with people that they normally wouldn’t get a chance to. So, I think it’s really important for people of all backgrounds to be filmmakers. The reason I wanted do it [so] soon is because it has incredible relevance. These situations are still going on. The first thing is that the young African-American has his life cut short by violence. That happens all the time and it’s not showing signs of slowing down. That’s one of the reason why it’s important to not wait 20 or 30 years – if you wait 2o or 30 years, there might not be any of us left at the rate we’re going right now. Another thing that’s at play is that this guy was killed while he was unarmed by somebody who was making presumptions about him, and we’re seeing it happen constantly. It’s still going on. When I was writing this film, it was four years ago. How many times has it happened since, you know? It’s so often that [politicians], juries, government, law enforcement is made up by people who never come in contact with people like Oscar. The only contact they have is through the media. So, if their only access to young African-American males is through the media, then shouldn’t media have input from people who have a close perspective on what it’s like?

Fruitvale Station is now playing in select theaters and opens nationwide July 26.