Already Home

09.01.2011

ART & DESIGN

Franklin Sirmans has big ideas about art. Sirmans, a native New Yorker, is head curator of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Arts. “How to think about an encyclopedic museum,” he says. “That’s what we’ve been thinking about and trying to do.”

Sirmans combines a traditional background in art criticism —he studied art history at Wesleyan University—with a desire to provoke dialogue in the gallery space. He is faced with challenges common in museums of the modern day, to create exhibitions that attract new visitors into the fold. “People who don’t have that experience and introducing them to the museum is exciting for me.”

Sirmans has organized several exhibits that were ahead of the cultural pulse. He served as guest curator for “One Planet under a Groove: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art” at the Bronx Museum of Art in 2002. “I think at some point it will be necessary to look at hip-hop in cultural context,” he says. “It’s so much a fabric of our generation or our lives. It’s everywhere, so now I don’t see the need to look so closely. Everybody is somehow touched by hip-hop.” He was co-curator of “Basquiat” at the Brooklyn Museum, an exhibition of Jean Michel Basquiat’s work, which also traveled to LACMA and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. “Rick Ross is dropping Basquiat,” he says. “Times have changed, I suppose.” He also curated “NeoHooDoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith” that traveled from Menil to P.S 1 Contemporary Art Center in 2008.

He left his curatorial position at the Menil Collection in Houston in 2009 for LACMA. In two year’s time, Sirmans has helped shepherd some of the current and upcoming provocative exhibitions of work at LACMA. He visited Ai Weiwei, the Chinese artist and political activist at his studio in preparation for the current exhibition, “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads,” that runs through Feb. 2012 at LACMA. “I was at the studio last winter. We had this conversation about (historical references) that he has in this one piece. He was looking at objects that come from Chinese antiquities.” Ai Weiwiei explores themes that speak to Sirmans’ interest in using past references in a modern-day context. “He is a contemporary artist and an important thinker in our world who is looking at historical material,” Sirmans says.

First shown at the Sao Paulo Biennial, Ai Weiwei recreated the twelve bronze animal heads that once stood on the grounds of Old Summer Palace in Beijing on the Zodiac Fountain in Yuan Ming Yuan. In 1860, the heads were looted by British and French troops during the Second Opium War. Five of the animal heads remain missing — and Ai Weiwei investigates the meaning of this cultural loss in his sculptures. “He’s thinking about the history of historical iconic images and redoing them for the moment. It has something to do with a dialogue between past and present.” Chinese authorities imprisoned Ai Weiwei for nearly three months this spring. “It was not ideal with him being contained,” Sirmans said about the process of organizing the exhibition. The work will later be shown with four jade zodiac animals from LACMA’s collection, adding another layer of historical context.

Sirmans is anticipating a varied response to “Five Car Stud” a poignant life-size black and white photo by Edward Kleinholz, constructed during the Civil Rights era, which has never been publicly shown in the United States and opens in September at LACMA. The work depicts a group of white men torturing an African American man whom they have discovered socializing with a white woman in the dead of night. Four cars and a pickup truck surround the horrific scene, with the headlamps position as spotlights on the beating. The work was shown only in Germany in 1972, and has been in a Japanese storage facility for over 40 years.

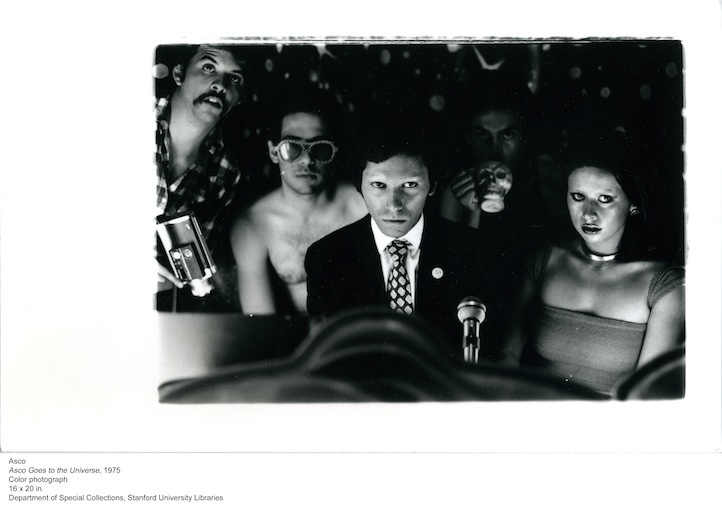

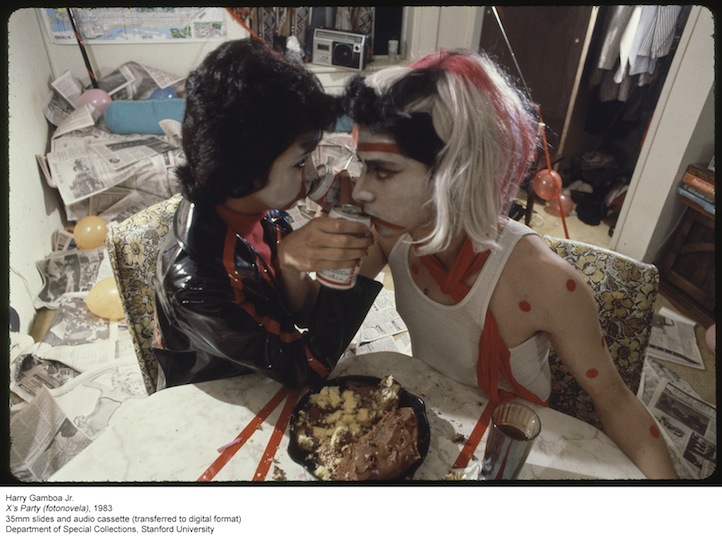

It is part of the museum’s mission to include the work of important local Los Angeles artists. “You’re already working with people from all over the world,” he says. “ It makes for an interesting dialogue.” The museum will present the first retrospective of the Chicano performance art group Asco that formed in East Los Angeles in 1972 in September. The collective responded to the socio-political tensions through performance, multimedia and public artworks.

Sirmans continues to write prolifically about art, including the introductory essay for Glenn Ligon’s retrospective that debuted at the Whitney Museum of Art. That exhibit will travel to LACMA in October. Sirmans see his role as somewhat of torchbearer, in the exhibitions he works on with his director and curatorial staff. He references an essay he recently wrote for an exhibition. “It ends with the quote ‘My job is to find the cave and hold the torch,’” he says.