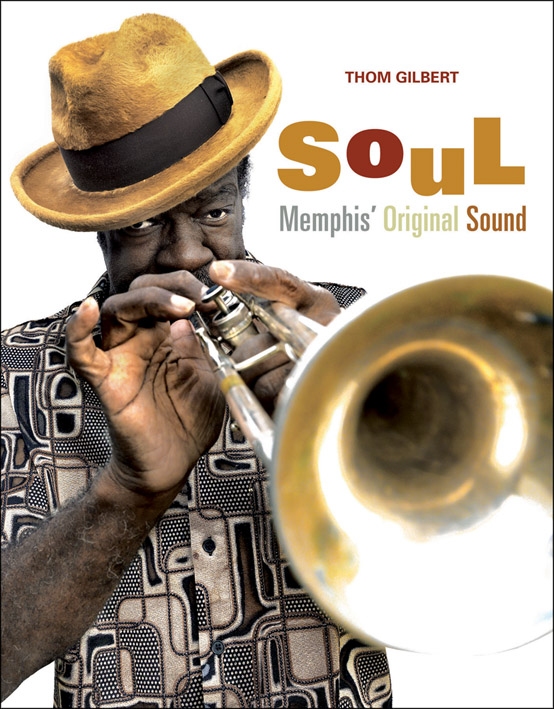

Photographer Thom Gilbert Discusses New Book “Soul: Memphis’ Original Sound”

12.22.2014

ART & DESIGN

If a picture can speak 1,000 words, then author and photographer Thom Gilbert’s Soul: Memphis’ Original Sound is comparable to an encyclopedia. Aside from a few brief pages of text, the book consists of more than 200 intimate, pristine portraits documenting the people, places and items responsible for the soulful Memphis sound of the 1960s and ’70s. From B.B. King to Isaac Hayes‘ Cadillac to the Lorraine Motel, Gilbert’s book is a history lesson in soul, especially showcasing Stax Records – home to Hayes, Sam And Dave, Otis Redding and others – and Royal Studios, where Al Green, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Syl Johnson and others cut timeless classics.

Here, Life+Times talks with Gilbert about Soul: Memphis’ Original Sound.

Life+Times: Talk about the concept for the book and what your goal was in documenting this scene.

Thom Gilbert: I’ve been a fashion photographer most of my life and started getting into a sort of rebirth where I wanted to connect with people on a real level rather than something that’s synthesized through makeup and hair and concepts. It started me on photographing what I call “Iconic Americans.” I started to travel some around my fashion assignments photographing the backbone of America. As things developed with different subject matter, someone told me that Royal Studios in Memphis was where Al Green did all of his recordings and some of the Stax Records ’60s and ’70s soul hits were done there. So, I decided to contact not only Royal Studios, but Stax Records too, and see if I could get over there. Royal was like, “Sure, come on over.” So, I set up a very small studio, just a light and a little pop-out white backdrop. I’m very influenced Richard Avedon and I really like anti-location. I like the feeling when I’m doing a portrait that it’s just me and them. I set up a few people to come over there through my contacts at Stax. I invited Bobby “Blue” Bland to come and he came for me to photograph. The whole place came to a standstill when he walked in. It was incredible. Luckily, the day that I was there, the Hodges brothers, who backed up Al Green and many others, were there recording with someone else. The project really snowballed from one person to another. As you can see from the book it’s everyone from B.B. King all the way to the newest comer at the Stax label Ben Harper. Everyone wrote little notes in my journal about their experience in those days and most of them are extremely thankful.

L+T: Are those notes the text that accompany most of the photos?

TG: Yes, it’s they’re own handwriting and it was just scanned.

L+T: How were able to find all of these people?

TG: You have to sort of be a detective. To tell you the truth, one person knows another person who knows another person and it snowballs. If you’re sincere and your motive is absolutely honest, it always works out well and that’s my approach. When I photograph, it probably takes me a couple minutes at most to do the portrait. If you can’t do it within that period you’ve pretty much lost them. I only needed to go to Memphis, Nashville, some offbeat towns in Tennessee and a few in LA, but for the most part, they’ve pretty much stayed within a certain [radius] of Memphis. I also went to Chicago where Syl Johnson and others are.

L+T: How long did the process take for you to not only take the photos but also put the book together? Some of the people, including Bobby “Blue” Bland, have since passed away.

TG: Probably a year-and-a-half. He’s not the only person that died within that time. I feel so bad when that happens because with a lot of these people I feel like I have new friends, and then all of a sudden, I heard [the news]. The other thing with the book – speaking of people no longer living – was that I tried to get artifacts, personal belongings, that have “DNA on them.” It could be a watch from Isaac Hayes, he also has a fur coat in there. I always try to get something that’s not memorabilia, but something that’s a personal item. I really lucked out with Otis Redding, I think I have a passport with his picture on it. You know that’s been in his pocket, so I felt great about that.

L+T: And this has also been made into an exhibit at the Stax Museum?

TG: Yes, it opened in November and it’s going through June of next year.

L+T: Describe what that consists of.

TG: Well, it’s condensed because of space. I prefer having large prints, so they’re pretty much twenty-four by thirty inch prints, I think there’s 80 of them. With all fairness, it was the museum that did the editing. Not to disrespect anyone that wasn’t included, we have a slide show with the people that weren’t included with prints. What I did was – and this was not something I set out to do, but as it materialized I realized I had something – when I was photographing someone who sang or played sax, something where they could perform in front of my camera if it was easy, I recorded it with my iPhone. For instance, as I was photographing Bonnie Bramlett, I asked her to sing “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man,” that’s the shot in the book and I recorded it with my iPhone. So, I probably have about 20 people that I recorded and it’s in a loop with the slideshow.

L+T: Growing up, what was your experience with Stax, Memphis soul and things that you were documenting?

TG: I’m a little bit later than it happened, but who can escape that music, even if you’re 20 years old. There’s so much tribute to that music in so many different ways that you can’t escape it.

L+T: One of the most powerful things about that music is how transcendent it was. This is the South in the ’60s, but the music touched everybody and brought so many people together. Talk about that element of it after being able to see much of it firsthand through your research and photography.

TG: Well, I’d like to preface by saying you have to realize that music in its true form has to have some kind of business attached to it or there’s no way for it to get out there. Especially in those days with no internet and social media, there really were only two ways anyone could hear anything unless you happened to stumble upon a concert: radio or buying a record. There’s a part in my book where I interview a gentleman Eddie Braddock. He was part of distribution at Stax. Speaking to him, he’s the actual person that got the Stax music – the Black music of its time – to get played on white stations. That was the decisive moment that Stax Records could be anywhere near successful, whereas before they were only getting played on Black stations and it just wasn’t broad enough for a successful business. That’s when it really, really blossomed. He’s very instrumental in the success of crossing those barriers of race in the 60s with music.

L+T: What were you able to learn about that era that you may have not know previously?

TG: Well, there is a very interesting thing. When you talk about an era, I’m thinking in terms of the era of Memphis and that soul music, as opposed to the era of Detroit and Motown. It was kind of like two battling businesses. Dr. Mable John was with Motown and was the first person to be signed to Motown. She wasn’t crazy successful with Motown, but she realized there was a big difference between Motown and Stax. Motown was sort of pre-produced. They had songs, they knew what artists they wanted to do it, they knew how they were going to do it. Everything was choreographed in the studio and Stax was totally the opposite. Stax, you go in and it’s “Who’s got a song?” Or, “Let’s write a song.” “We’re gonna go to the Lorraine Motel and write some songs and be back tomorrow.” They were able to nurture and develop a song with the artist, not hand-deliver it to them and tell them, “This is for you, let’s record it.” So, it was a very creative palette for Stax artists. You can certainly tell a huge difference between Motown and Stax in that way.

Soul: Memphis’ Original Sound is available now. The Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis is hosting “Soul: Memphis’ Original Sound by Thom Gilbert” through June 30, 2015.