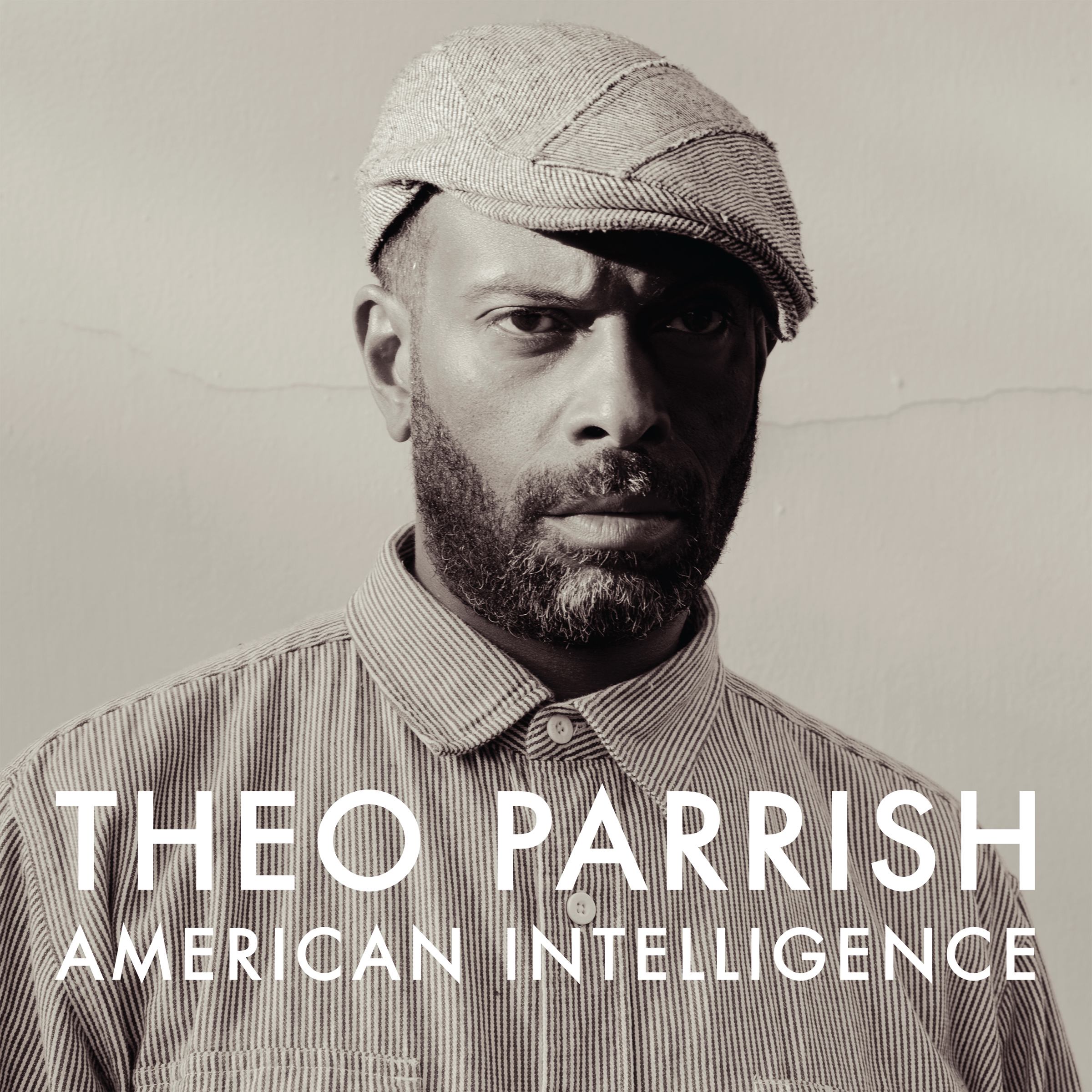

Theo Parrish Discusses New Album “American Intelligence”

12.05.2014

MUSIC

“I find it amazing that there’s been a ramp up in these kinds of killings since a Black man has been in office,” DJ, producer, selector and musician Theo Parrish ponders. “And so you wonder, is that reaction to him being in office? What I’m seeing is these are systematic killings. It’s a lot of things at once and it’s crazy that this has happened right as this is coming out.”

His latest album, American Intelligence (out December 8th), is what is coming out, and it’s on the heels of the recent verdict found in Ferguson, Missouri. Some may call it dance or techno – some call it groove music – but the muses are often real and sobering. Born in Washington, D.C., spending time in Chicago, Kansas City and Detroit, and now playing everywhere from LA to London to Dubai, there is plenty of experience and influence for Parrish to pull from.

Intelligence, his first album since 2007, features over two hours of material, much of it trancelike or spiritual; ultimately, the sound becomes a sanctuary. Life+Times talked with Parrish about American Intelligence and finding the groove.

Life+Times: Talk about the album title, American Intelligence, and what that means. It sounds like something that’s become even more relevant in light of the recent events in Ferguson.

Theo Parrish: It tripped me out. Being American and coming to Europe, a lot of times I would run into this comment, especially doing dance music – or what’s considered dance music – they get surprised that I have command of three and four syllable words. That was one aspect of it. Then a couple of events started happening to me – this is all before I started to name the album. Crazy events were happening like police stops. I expected that as I got older there would be less of that. But then, it seemed like there was just a ramp up of lynchings. A lot of them and blatant, blatant, blatant. Being able to bounce back and forth [between America and other countries], I just started to see this perspective of how America is a really, really crazy place. On one hand, there’s all this beauty. But [on the other hand], people say, “America is on the decline.” And I say, “It’s been on the decline for years. We were born into its decline.” What has to be realized is there are no more American exports anymore – no one wants our bread, steel, cars, etc. – all they want is our guns and our art. And we’re not even good at giving the guns anymore. The very thing that makes America so mad, creates the commentary on its insanity, that’s the art part. The scary part is now I’m seeing a lot of that be perverted. A lot of the stuff that’s coming out artistically is thin, vacant and plastic, and a lot of it is coming from Black people and a lot of us are poisoned by this plastic thing. If we get to how we really feel, we’ll run around crying and screaming all the time. It’s a paradox and there you have the title. It’s many things all at once. It’s seen as a paradox to be an American and be intelligent. Some would ask is that even possible?

L+T: Given everything you just said, how do you translate those things via your art and your sound as an artist and musician?

TP: There’s a certain amount of freedom that I try to get to or express to people. I’m very much not into boundaries in terms of, “this is house music or techno music or R&B.” Those are all just marketing tools. What I try to get to is that part of everybody that is childlike and is simple, it goes to the rhythm, the repetition. The idea of a handclap that keeps happening over and over again is the most simple thing that can happen and is something everybody can do and relate to. The concept of these songs being trancelike in some places, narrative in other places, trying to be as reflective of what my command is in terms of skill, which is doing my best with what I have. The idea of pure expression, making people be able to move and feel like they can be themselves or like they can let go of their masks. You go through all these times in a week where you’ve gotta dress this way to eat, or be this way to relate, or talk in this other way to get by. When you’re hearing this, this is for that release when you’re in your most comfortable place. That’s the emotional standpoint of where I like to be in terms of expressing it. Luckily, a lot of that has been ingrained from when that was happening for me when I was in Chicago.

L+T: You mention Chicago, and you’ve spent time in Detroit and other places, too. How have those places, and the different things you’ve seen and heard there, influenced your sound?

TP: To go back [to Chicago], one of the main points was the mix shows with Farley “Jackmaster” Funk, WBMX, those sparked the interest back in the ‘80s. Going out to some of the parties, catching Ron Hardy a couple times, catching Lil Louis a lot, catching those old house DJs had a big impact. Also, too, going away to school in Kansas City, I got introduced to jazz and all kinds of stuff there, then going to Detroit, the business side, the DIY, came in there. Then bouncing to Cleveland was the funk thing. The most common [thing] is that it’s a midwestern feel and sound. The thing that comes across in all those cities, traditionally, has been the funk, those hypnotic, trancelike things coming in. The house, techno and later hip-hop, knowing that all of this is the same music and basically coming from the same standpoint of being outside of the regular society and also being able to tell your own story. It’s become difficult for us to recognize our own sound because it’s not promoted and that has to do with the way that music has changed. It shocks a lot of Black people when I say, “Yo, this is your music. ‘Techno’ and ‘house,’ this is yours.” It’s strange. But those cities, Cleveland, Kansas City, Detroit, Chicago all played big parts, mostly having to do with system music. You gotta go to a spot, lights out, nothing but brothers and sisters in there and they’re snapping to some serious tunes. There’s no video to go along with it, no fancy shirts and glitter that we consider club stuff now. There’s none of that. It’s raw dog, it’s ours.

L+T: Talk about “Be In Yo Self” and the process of putting that record together.

TP: That song started from a situation I was in dealing with a relationship. The idea of “Be In Yo Self” is a play off of “being yourself.” Being yourself shouldn’t have a downside. It started with this one sample in there and I was like, “what else does this need to be?” I called in a good buddy of mine Duminie Deporres, he plays guitar. He laid some stuff down and I also have a singer I’m working with named Ideeyah. I was thinking, “what does it need to be?” And I was like, “be myself,” and I just followed the groove and added all these different parts that seemed to make sense. It mixes and changes because then it turns into, “dance a little closer.” It’s almost kind of like a spiritual. It’s a chant. Being yourself shouldn’t have a downside. It shouldn’t. Because of what I was dealing with, I wanted to express to this person that I don’t want to push you away in being myself, I’m asking you to dance closer to me. The mixing process and how much I went through to do that, that was the last one I finished for the album. I have so many versions of it, but it was a difficult one to get because it’s kind of soupy and there are so many different places where things need to pop out and come forth. It was quite a journey to mix it. It started with a couple of samples then went into a whole ‘nother trip.

L+T: At what point do you know that you’ve found a groove?

TP: It’s easy. It’s gotta make you make that stank face [laughs]. If something makes you make the stank face naturally, then you’ve found something. I was talking to someone, like, “what is it that makes be go ugh?” Why do you frown when you do that? I think you’re smelling someones actually spirit at that point. They’ve translated the most raw and immediate emotions that they were feeling at that point and they were able to commit that to a record and you’re hearing that back. Sometimes it’s only for a couple bars. A lot of time we’re talking about live musicians, so they’re locking in and they’re giving their person. When it happens you can feel it and hear it. Sometimes, when you’re fooling around you can find it. The idea of knowing music intimately enough and it being that much a part of your life that you let it into your person so you can recognize a pocket. A lot of people call that “a pocket” when you’re really in there popping. It resonates with you, like, “damn, that feels good.” A good example of that would be Donny Hathaway’s “The Ghetto.” There’s a point where you can hear the crowd and they’re with him, they’re on the same point. Those kind of moments where it’s clear that there is a humanity being expressed and that humanity is zapping right to you. That’s how you know you’ve got a groove.

L+T: George Clinton, for instance, talks a lot about groove music and jazz artists talk often about being in the pocket. Those are more traditional musicians and you’ve brought some new elements to it. How are you able to talk these sound sculptures, loops, live instruments and voices and form your own sound that is still relevant to what a jazz or funk artist are doing?

TP: That’s the thing. There’s always been that tension between modern musicians and traditionalists, and it often becomes a thing where most times the modern musicians – I consider myself a modern musician because I don’t play a violin or a horn, and I’m doing a bit of this and a bit of that – there’s these new technological ways of making stuff and making music happen. Because a lot of that initially had to do with sampling, that would offend a lot musicians, like, “Oh, they’re just chopping stuff up.” I used to have these talks with my uncle, I was like 13. I would play it for my uncle and he’s like, “Where’s the talent in this? I don’t hear any talent.” Number one, it fired me up. It took me years, and later I understood where he was coming from. He’s a trained jazz musician and went to Berkley. For him, if you didn’t know how to read or write what you were putting down, and beyond that, if you didn’t how to play it on time, in time with everybody else that was there – the idea of community – conceptually, that’s like the antithesis to what he was talking about. To him, that was his McDonald’s, musically. But there was a journey that I was to go on, a refinement in that process, [I] ended up sampling less. Writing is no different than placement and timing and cohesion, and that community is something you strive for when using the machine because the machine will simulate that community. The other biggest difference between traditionalists versus modernists is that there is always a new technological thing. We’re dealing with machine and man, and that is one of the biggest things that we’ve been challenged with in the 20th and 21st century, this concept that the raw musicians need the technology to get it out to the people. That’s just a fact. A lot of them used to feel that was something to crash against, that’s not the case anymore. What happened with me is I would use live elements: I would turn the timing off on a lot of stuff, I would learn more and more about playing keyboards in a way that made sense to me not necessarily on the ones and the thirds. Therefore, it gets loose at points, then tightens up at points, then gets loose. Sometimes, I turn the sync off altogether. Eventually, I went into working with live musicians, playing live and conducting a band. Here’s the mistake of a lot of modern musicians: they’ll rely so much on technology that they don’t even know how to play their own tunes. Knowing your songs, knowing what you’re doing and understanding what you’re translating across to other musicians, that’s gonna get your respect from them. That’s gonna make it transcend.

American Intelligence is available here.