The Word

03.14.2012

LEISURE

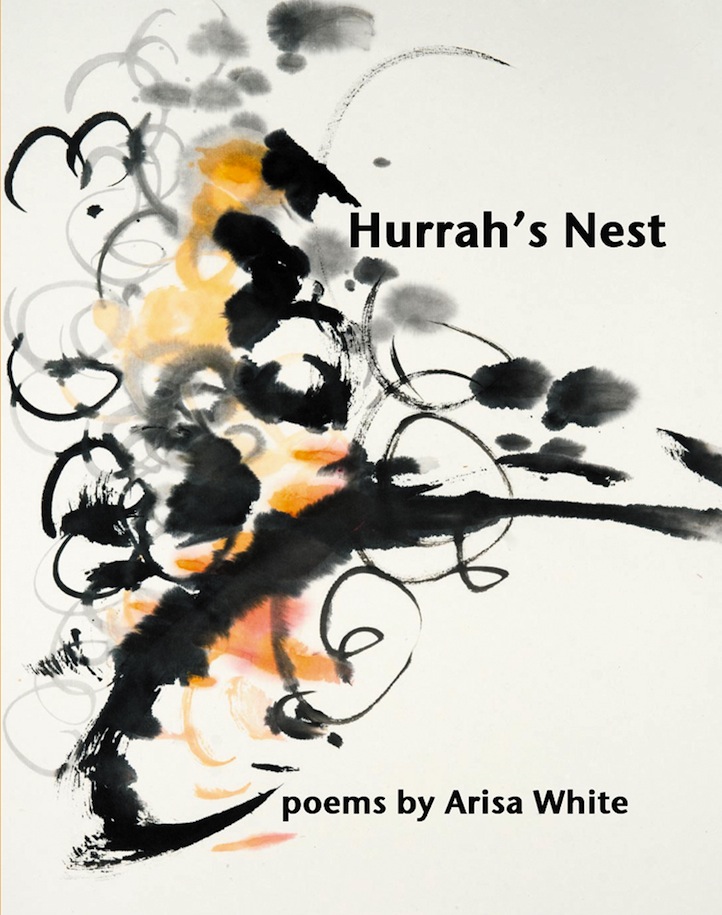

Arisa White’s debut collection of poetry Hurrah’s Nest works in many ways as narrative prose. Her vivid collection works as a kind of biography of a family, or a neighborhood. But always there is flow – almost musical – which can’t be entirely credited to her Caribbean roots. White is casual yet careful with construction, she makes deliberate look easy. Her poems are not without politics, but they do tend to come with no judgment. In her poem “Subtext…” she unpacks a life in seven stanzas:

“Pregnant at fourteen, swayed by a boy

not gentleman enough to take off her coat.

Six kids later, she sleeps with a Jamaican mechanic

Who gets drunk and leaves her a bouquet of bruises.”

Here, I talk to the Sarah Lawrence and UMass, Amherst, grad about her first reads, making a living as a poet and the hierarchy of page poetry over spoken word.

Life+Times: What were your earliest experiences with literature?

Arisa White: Mostly I did a lot of reading. I read anything that was at my mom or grandma’s house – encyclopedias, Agatha Chrisie, Jamaica Kincaid, Terry Mcmillan, Octavia Butler. Around 6th grade, our teacher was really into building our vocabulary and part of those assignments were to write stories with SAT words. I’d rewrite the lives of characters from A Different World. I rewrote Dwayne’s life. I put Whitley in the ‘hood. My teacher shared our stories with her sister and her sister couldn’t believe these stories came from 6th graders. And that’s when I realized you can put on a guise and create a whole world that doesn’t necessarily connect to the author’s personal history and something about that fascinated me—I could be a trickster.

L+T: Hurrah’s Nest is concerned with family. It reads like your family. How did you navigate issue of privacy?

AW: I just wrote and then I realized it was going to be about family. Initially I tried to change their names, but that didn’t work because the poems were constructed with the music of their names: Kayana, Uriah, Jamar. So I got their permission to put it out there, which meant giving it to the family to see what they thought and I was nervous. I thought they’d think I betrayed their privacy, but they loved it. I was relieved. However that came at the end when I was putting the manuscript together. During the years it took to write these poems, I focused on the writing, on getting my truth out, otherwise I would’ve never written these poems—I can be very sensitive to what others think.

L+T: How do you make a living as a poet? Do you have to teach? A lot of poets would love to know some of the practical things they should know when they think of doing this…

AW: Number one: don’t focus on the money. What I do is I work. Around 2008 I realized I couldn’t just do poetry, I had to do something else. For me poetry is about all the things I’m doing in my life, which includes my work. So it came down to me doing work that allowed me to keep poetry as a top priority. For me that means writing for magazines and working remotely, so if I have to travel or go away a month for a fellowship, I can. I’ve been a bit resistant to academia and teaching, but I’m considering. I do writing workshops in the community. I recently did one with high school students in Oakland and that was an ideal group to work with. I’ve been more proactive about making more of those opportunities happen. It’s also about being realistic—yes, as a poet I have to have a job or a rich partner [laughs].

L+T: Who are your favorite poets?

AW: There are so many, but some of my favorite poets are Hart Crane and the Irish poet Medhbh McGuckian, who I just adore. For contemporary poets: Tyehimba Jess, Rebecca Seiferle, Claudia Rankine and Terrance Hayes whose recent chapbook deals with race from a sci-fi perspective.

L+T: What do you consider the differences between spoken word and poetry?

AW: Growing up in New York, I’d go to Brooklyn Moon and Nuyorican and Kokobar and all these places where there was spoken word, so it holds a totally special place for me. I can see where it diverges from page poetry but they both work the same for me. With spoken word, I came into my own political voice and sensibility as a young woman growing up urban and poor. It provided a space for me to make social and personal connections and to think of myself as a citizen. When I’m working on the page, I focus more on the word, the syntax, the actual line. I have respect for spoken word, I consider it a genre of poetry and it has its place in the canon. When I’m working with kids whose poems come off more performative and spoken word, I give them tools to better their line structure or improve their metaphors. I believe each has its place.