The Director of “Long Distance Revolutionary” Speaks on The Story of Mumia Abu-Jamal

02.18.2013

LEISURE

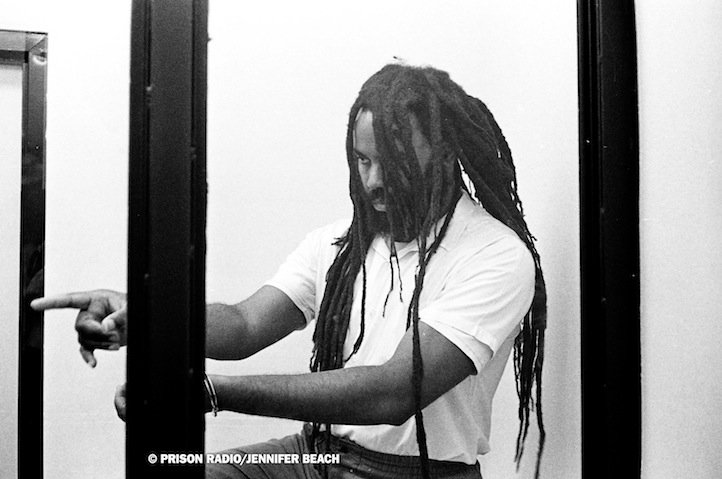

One of America’s freest voices comes from a man behind bars and on death row for nearly three decades. Mumia Abu-Jamal’s resilient fight for not only his own freedom, but injustice in America in general has garnered him much national attention and support. A budding journalist growing up in Philadelphia, Abu-Jamal has continued to write and broadcast despite being locked down. Beyond his own voice, countless others have written books and essays, spoken about him and created films, usually dealing with his controversial court case. In the latest look at his life, film documentary Long Distance Revolutionary looks past his incarceration, instead focusing on Mumia as a journalist and the power of his voice. The film opened earlier this month in New York and is beginning to make rounds across the country.

Life+Times talked with director Stephen Vittoria to get the story behind creating Long Distance Revolutionary.

Life+Times: What drew you to doing this film about Mumia?

Stephen Vittoria: You know, you wake up in a country and you try to look for some sanity. You realize that from a political standpoint, the country is being run by folks who choose war over peace. You have economic rapists just ruining people’s lives and then you have general run-of-the-mill racist psychopaths that, after 400 or 500 years of slavery, still want to use a racist mentality to go about their business and I was looking for some sanity. For me, sanity existed – as I’ve told many people – in a dark, dank hole on death row in Pennsylvania. I had been inspired by Mumia’s writings and his broadcasts for many years and I was making a documentary entitled Murder Incorporated: Empire, Genocide and Manifest Destiny, and Mumia recorded about 25 answers to 25 questions that I had for the film. For various reasons, I decided not to complete the film but that started my relationship with Mumia and very firsthand working relationship with him. A number of the same contextual [ideas] that you will see in Long Distance Revolutionary were also present in Murder Incorporated, so it was an evolution to doing the story. Mumia’s story always intrigued me because of his commitment to peace and justice and freedom from inside [prison] where harsh and draconian pieces of the American empire really inspired me to tell the complete story and I think many people would agree that the film is a definitive work on his life.

L+T: Talk about your approach to telling his story, not dwelling on his case, but making it about his life and his work.

SV: Sure. Well, clearly, it was a very conscious decision on my part for two reasons. The first reason was very practical: up until this point, for all these years, every film, book, article, even live event that’s ever been produced about Mumia has focused solely on his case, and that’s understandable. I understand why that really intrigues people. But had I made another film about this case, we probably wouldn’t be having this conversation now because I would have had an un-distributable movie. John Edginton‘s HBO movie, Mumia Abu-Jamal: A Case For A Reasonable Doubt?, even though it was made 15 years ago, did a very good job at presenting the reasons why Mumia needs a new case. There was no smoking gun that I could have presented in a film that would have changed much of what John did. I could have maybe added 10-15 percent, but really not that much. So, as a filmmaker, you never wanna make a film about something that’s already been done and done a number of times. From a creative, aesthetic standpoint, I think Mumia’s life is much more epic and broad than just December 9th, 1981, the night that he unfortunately was arrested and later convicted for the killing of Daniel Faulkner, the Philadelphia cop. I saw a life that began in his early teens as a great questioner of authority. Someone that at 15 years old is writing some serious revolutionary work for the Black Panther newspaper. 10-12 years later at the age of 26, he’s a full-fledged reporter for National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, he’s a rising star in Philadelphia journalism at the time and fiercely independent. He’s gaining jobs because of his talent, he’s losing jobs because he refuses to compromise. Then he has this horrific experience on death row with death warrants over his head. Three or four times he was within days of having his life snuffed out from under him and he’s still writing, he’s still broadcasting. His work has evolved on death row and in prison from writing specifically about the prison industrial complex, mass incarceration, the school to prison pipeline especially for African-American males and males of color, to being an incredible critic of the American empire and imperialism. So, I’ve watched his writing really increase from writing about what he knows to writing about what he’s learned and what he feels, very much like a Howard Zinn type of historian. That’s what intrigued me the most about Mumia’s story.

L+T: In the film, you told a lot of the narrative through people reading various excerpts, sometimes they were children, sometimes adults, sometimes famous people. Why did you have these people reading these excerpts from Frederick Douglass, Manning Marable and others?

SV: I wanted very much to have the film be a journey with Mumia, and throughout Mumia’s life his words and the words of others come to him and people that are Black, white, Hispanic, Asian, young, old, and I noticed that in his writings and the research that I did for the film, he truly was an everyman. As a young man, he would go around the neighborhood and meet with the clergy. 10 years old asking them about God. He was inquisitive about spiritual matters. So I wanted to bring to the table particularly people that no one would recognize but were really good performers, from children to older folk to kind of echo the idea that many people were moved by Mumia’s writings as he was moved by many other people’s writings. It was a real conscious effort to engage as many people as I could. There were a couple famous people, Ruby Dee, Giancarlo Esposito, Peter Coyote, but you’re right, for the most part, they were actors that I knew or found just from casting. I knew it was important to bring Mumia’s words to life and I wanted to have a really strong cast to do that because his words are brilliant.

L+T: Did you learn anything about Mumia, Black liberation or American history in creating the film?

SV: I sure did. One thing I learned about Mumia – and I consider him a dear friend now – is that he’s kind of a nerd and he can be very incredibly funny. We see him and he’s very radical, he’s committed to his message and he’s a very serious professional, and all of that is true, but what you also find out about him is he loves reading comic books, he loves having fun. Most of our meetings together in prison I would say the vast majority was spent laughing and joking about things. It’s not a real serious situation. So that softness in Mumia is something that I absolutely learned. From the sense of American history, I have learned so much from Mumia’s point of view of the American empire – I always knew it but I never really felt it, and now I feel it – how the American empire and a very serious, repressive apparatus comes down on the African-American community. Even a cynic like myself never really understood the damage that the empire has done to African-Americans over the last 500-600 years. I think that’s one of the great additional lessons that I’ve learned from Mumia working with him and his writing.

L+T: There were a couple points where you talked about Muhammad Ali or used images of him. Talk about the parallels between Muhammad Ali and Mumia; the name change and really standing for what they believe in.

SV: I’ve always been a huge Ali fan since I was a kid and the parallels to me were striking. Obviously both men giving up their slave names, both men never compromising at great loss to themselves, personally, financially, physically, spiritually, they never stepped off the path. They held something to be true and to be right to themselves and they would fight to the death for it, and I saw that in both men. I also saw it in some of Mumia’s writings. Some of his mentions and remembrances of Ali was something I wanted to bring to the foreground. Just from talking to him and reading and hearing some of his stuff, it seemed like Cassius Clay aka Muhammad Ali was someone that meant a great deal to Mumia. So if it meant a great deal to him, as a filmmaker, I wanted to shine a light on it. You’re absolutely right, the connection between the two men is palpable and there’s a really strong connection between the two of them, and Mumia continues to speak about Ali when he has the opportunity.

L+T: A lot has been made of the powers that be trying to deter Mumia’s voice from being heard. For you doing a film about him, were there any barriers that you ran into or people who were trying to shut you down?

SV: When I was making the film, no, because my company Street Legal Cinema financed the film, so I didn’t have any suits around my neck tied around my neck and I was able to have free reign making the film. There were some people that wouldn’t come on camera with us, primarily people that were historically anti anything Mumia, and that’s unfortunate because they had their opportunity to say what they wanted. Where I noticed some of the silencing seems to be more in the marketing of the film. First Run Features has been a fiercely independent distribution company from the outset and I give them kudos for embracing the film, taking it on and fighting to get it out there. The people associated with the film, the audiences that we’ve seen in New York and the film festivals, have embraced the film with a passion and fervor that I’ve rarely seen associated with a film. But I don’t think the release of the film matches the fervor that I see. If you read the reviews, some of them have just been stinging in their taking on the film and the fact that Mumia is being presented in this way as somewhat of a heroic character, that the film doesn’t deal with his case. Some of these people can’t get their heads around that. But I think we’re making inroads because the New York Times – who I did not expect a decent review from – gave the film a very decent review, and in the very first line, the writer referred to Mumia as an activist and a journalist, and we all took that as a victory. Maybe we’re changing the discourse, because up to this point, he’s always referred to as convicted, crazed or communist cop-killer, and for the Times to do that I thought was a strong indication that the film had an impact on that writer and other people. The theater chains and theater owners really have not embraced the film as much as I thought they would. We did incredible business the first week in New York City, we were number three in the country and I’m not sure if that’s going to add up to anything, so we’ll see. The audiences come to the film in droves and they love it. As a filmmaker, that’s all I really care about is the audiences.

L+T: You’ve said that Mumia’s sister was the most interesting person that you talked to. Who else did you talk to that had fascinating insight about Mumia or American life in general?

SV: I can tell you an obvious choice would be Cornel West. I can speak to Cornel and talk to him and he will forever intrigue me. Dick Gregory was an incredible interview. One of the unfortunate things as a filmmaker is you can’t put everything in the film. We’re gonna try to put more on the DVD when it comes out so people can see some of these interviews. Alice Walker was incredibly insightful. Ruben “Hurricane” Carter having been in a very similar situation himself had great insight into Mumia’s personal hell. Someone else that really brought a lot of Mumia’s past life to the forefront was Barbara Cox Easley, who was with him in the Black Panthers in Philadelphia and talked about how Mumia was never a chauvinist. He had incredibly open arms to all colors, both sexes at a very young age, and I thought that was really [remarkable] for Barbara to talk about his embrace of women as equal partners. I think Mumia got that from his mom. He had a very strong relationship with his mom and a huge amount of respect for her life and how hard she worked.

Click here for more information about Long Distance Revolutionary.