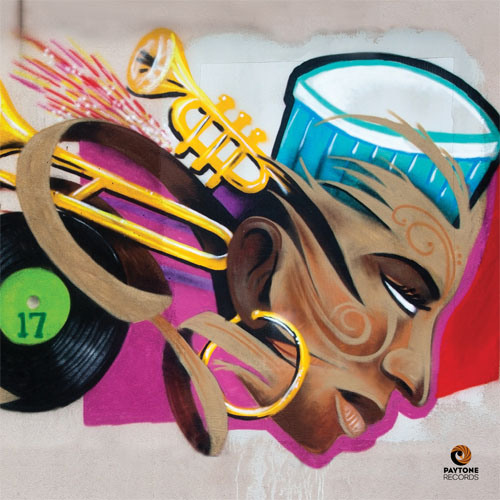

Nicholas Payton Talks Latest Album “Numbers,” Black American Music, and More

08.05.2014

MUSIC

In the liner notes of his latest album, Numbers, multi-instrumentalist Nicholas Payton states, “I wanted to leave space for the listener to think, or for cats to play, sing or rap over it.” The open-ended approach makes for a funky, soulful journey uninhibited. In recent years, his long-form writing and bold critiques of jazz, hip-hop, politics and everything in between posted on his personal blog have garnered plenty of well-deserved attention, but his musical voice remains prolific and preeminent. On Numbers – each song title is literally just a number – he recruits Virginia quartet Butcher Brown who are equally as soulful and fearless as he is, and vibe organically with the New Orleans native at every turn.

Known primarily for his trumpet playing, Payton only brings his horn out for the first tune on the album, and plays the Fender Rhodes the rest of the way. As a result of the approach and chemistry with Butcher Brown, he says, “we may have recorded the hippest, funkiest, play-a-long album that’s ever been documented. Musicians, rappers, singers, DJs, and lovers have in this collection of records an album designed for you to float on top of.”

Life+Times caught up with Payton to discuss Numbers, Black American Music and more.

Life+Times: Talk about the concept for Numbers and the energy that’s on the album.

Nicholas Payton: These tunes are fragments that I’ve had sitting around for years that I’ve [used] to create compositions. Each tune has two to three 4 or 8-bar sections where I just copied and pasted these different motifs and fragments that I had sitting around. I didn’t know when I wrote these things that I would do that with them, but that’s what it came from. It was really interesting how when I put them together, it all just seemed to work when they weren’t conceived as a whole, these were just individual thoughts. When I was putting them together I was numbering them so I could remember which section was which. The titles, at first, were just placeholders; as I lived with the material more, I liked the idea of not having a formal title and the songs being open-ended. The music was open-ended because I left space – by calling them numbers – where you don’t have an impression of what the song is about. It’s not about love, it’s not about this, it’s about whatever you want it to be. It’s been a work, conceptually, in the idea of space, and there’s enough substance and groove and material there for you to listen to within that space. There’s still group interaction, solos, etc., but it’s just not done in a traditional way. I don’t really know of any album – to my knowledge – that’s ever been done like this. A song or two here or there, yeah, but a live album where it’s like a beat tape but it’s real interaction? I don’t know of anything else that’s been done like this.

L+T: So, they were all recorded in numerical order?

NP: Yeah, they were recorded in that sequence. The first day of the session we did songs two through six; the second day we did seven through eleven; and the last day, we did 12 and 13.

L+T: Butcher Brown assists you on every tune. In your prose, you’ve been critical of some younger musicians for not having proper knowledge of the history. What did you see in them that made you want to work with them?

NP: They’re soulful. They’re knowledgeable of previous styles, but they’re not trying to [copy] those styles. They have respect for the history, but at the same time, sound like today and they love to groove. They love to play pretty music and that’s really what I like to do. It just seemed like a good situation for me to work with some like-minded cats and, at the same time, further my idea of mentorship and passing on just like cats older than me took me under their wing and gave me opportunities. It’s a multi-faceted thing in working with them.

L+T: You only play trumpet on the first record, and then play fender rhodes on the rest. Why did you decide to do that?

NP: I didn’t originally decide to do that. The idea was that I would track on the rhodes; I left open spaces on a lot of the tunes for me to play trumpet solos. But as I lived with the material, I began to love it just the way it was and decided not to put the trumpet on top.

L+T: Your BAM (Black American Music) movement has been publicized a lot. When you talk about the Black music tradition, what are the common threads – regardless of genre – that link funk, hip-hop, etc., together?

NP: For me, the whole thing with those labels is it creates a chasm where there is none. To me, these things aren’t even different. The only difference in any of them is usually where the music comes from and who’s creating it. There is a rhythmic code, though, that exists in the best of all Black American music. Some of that DNA can be traced back to Africa and African rhythms, Haitian rhythms, Cuban rhythms, the rhythms of the African diaspora and how those rhythms changed when they were translated to the New World. You can say the same thing for New Orleans where you have bounce or second line grooves, or you have go-go in DC. The reasons – climate, food – all these cultural things go into how music sounds in a particular place: what kind of tempos people tend to like, how they play on the beat. People from Northern regions of areas where it’s colder, the music might be more on top of the beat, whereas Southern areas, it’s more laid back and behind the beat. Of course, there are always exceptions to these generalizations. You could do a whole encyclopedia study on specific rhythms, where they come from and how they’re transmuted. The most succinct way I can put it is that the thing that ties all Black music together is what I call the tribal DNA, a certain rhythmic code that exists in all great Black music. People talk about clave in Cuban music; clave comes from Africa. There’s a certain clave in Black music, too, in funk, hip-hop, soul – you hear it in a track by Run DMC, A Tribe Called Quest, Marvin Gaye, James Brown and so forth. It’s the same beat, the only thing that’s different is who’s playing it, where they’re from and what flavor they give it, but the DNA is still the same.

L+T: In the liner notes you say that you don’t write tunes anymore. What do you mean by that?

NP: I don’t sit at a piano and write songs. Songs write themselves and then I transcribe them. It’s been 10 years, really, since I’ve written music. That’s not to say I don’t compose, what I mean is I don’t ever sit down and say, “Ok, I’m gonna write a song.” The music comes to me, I’m not asking for it, I’m not beckoning it. It comes on its own. I’ll be doing anything and I’ll hear a melody, then I’ll go into my voice memo or play it on piano and save it. All the tunes on Numbers are like that, stuff coming into my voice memo, waking up at 3 o’clock in the morning, hearing something, playing it and then going back to sleep and leaving it. That’s what I mean by not writing music. To me, that’s not really writing; I’m not writing the music, the music is writing itself.

L+T: Is that process comparable to a hip-hop artist like JAY Z who doesn’t write down his rhymes?

NP: I would say that process is the same. I’ve heard the same about Lil’ Wayne. It’s the same thing, from the same place. That’s the real space. I’ve heard Lil’ Wayne say in an interview, “If you’ve got to write it down that means you don’t really know it, it’s not really true.” That’s my whole philosophy. The documentation part is for me to remember. When you record it, then you’re documenting it, that’s all I’m simply doing. When I go to my voice memo, I’m not writing the song – the song already wrote itself – I’m just putting it down in a form where it can be documented and preserved or performed at a later date. I don’t even remember what it feels like to write music it’s been so long.

L+T: You mentioned Lil’ Wayne and bounce music, and you’re an acute businessman yourself. Talk about New Orleans music culture and how its made you the artist and businessman that you are.

NP: I started playing professionally when I was 11 or 12 years old. I was making money at a time when most kids were still getting their allowances. My entrepreneurial hat was already on. Being around so many musicians who were autonomous – my dad putting together his records, having his own label, not waiting for people to hand him something – I was around a lot of people who were like that. As far as New Orleans hip-hop, watching how cats like Mannie Fresh tried to create their music as sample-free as possible. They were snubbed for a time by the East Coast hip-hop scene, but there’s something to be said for when they compose their music and they don’t have to pay licensing fees, that’s all money coming 100 percent to them. That’s to be respected business-wise.

L+T: Is there more space now, with the internet and being able to do more things autonomously and independently as an artist and musician, to create “Black music” and blur genres? People like yourself, Trombone Shorty, Robert Glasper, etc., have been influenced by jazz, hip-hop, funk, soul are creating music that is not confined to anything and doesn’t have any boundaries.

NP: It’s always been that way for me. I would say the difference with the advent of the internet is that there’s less and less of a need for the middle man. In fact, the middle man is obsolete. You can directly associate with your fans, which is something you couldn’t really do 15 years ago. There was always a go-between; now, you can go to the music store and for a couple hundred bucks get you a home studio. You couldn’t do that 20 years ago. The amount of money it would have taken to get a home studio, the average person couldn’t afford it. Now, the average person can afford to build their own studio and record at their leisure in their homes. That’s empowered a lot of musicians to do different things. Having a major record deal is obsolete. The way the labels function, they don’t have the same type of control or monopoly over the industry. Some kid could put a tune on YouTube and get several million views, have a career and a fanbase, and tour all over the world just from that. That was impossible over 10 years ago. The flipside is now anybody can make a record, the marketplace is flooded with a surplus of product and most of it is bad. There’s always been bad music, but there’s more of it now, so you have to dig a lot harder to find those jewels. Plus, record stores are obsolete. The Internet has changed the game, pros and cons. I think, ultimately, it’s better for the artist and the audience, but I don’t think we’ve navigated exactly how this is gonna work. It’s still pretty much the wild, wild west now. Anything and everything can go down, and it is going down.

Numbers is available now.