George Clinton Keeps It Funky: Goes Deep On New Book, Hip-Hop, Rock, and More

10.22.2014

MUSIC

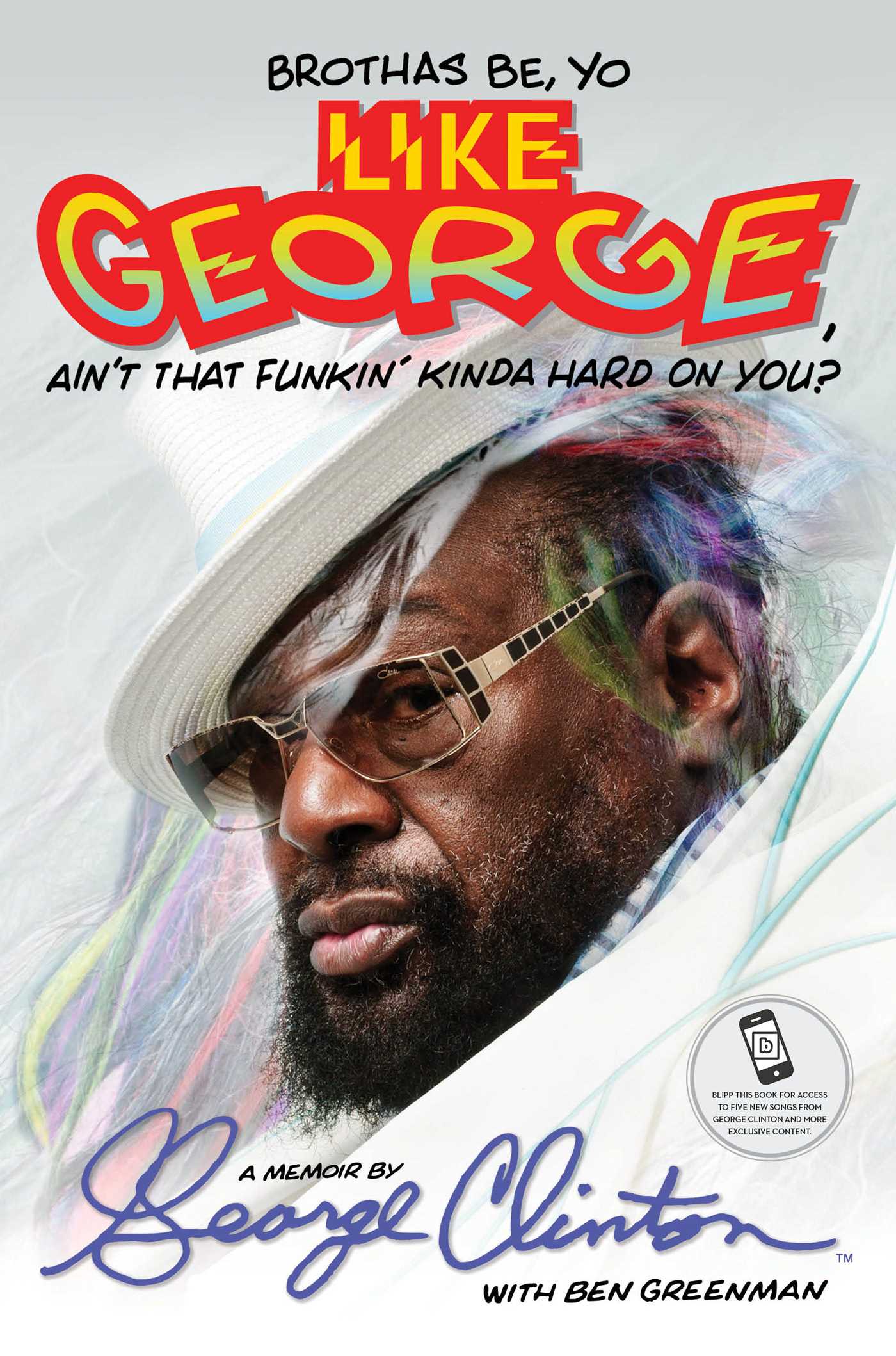

“I knew I had a hell of a story to tell, I could write three or four of these books and never write the same shit,” music pioneer George Clinton states talking about his new memoir, Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kind Hard On You?, out now. Equipped with more than a half-century’s worth of sex, drugs, funk and rock and roll tales, it’s a feat in itself that Clinton can recall so much so vividly. That’s what he does for nearly 400 pages and it’s ultimately for good reason.

“I did the whole book so I could tell this story,” he says. “We had gangs of fun and I ain’t regretting nothing other than now that I have to fight for these copyrights. I’m gonna fight for that because I’m 73 years old, I ain’t got nothing else to do other than being on the stage. I’m thankful for that fact. At BMI, they changed our names on the songs at the copyright office, like, ‘Oh, we didn’t know if Parliament was Funkadelic, George Clinton, Jr. or George S. Clinton.’ They’re doing this to everybody.”

In the book, he muses on everything from his days as a barber in New Jersey, to living with Sly Stone in the ’80s, to recent court depositions in Switzerland. Reminiscing and staying present all at once, he also mentions recently working with Kendrick Lamar and the new album he’s got coming out. Life+Times talked with Clinton about his memoir, rock and roll influences, Jimi Hendrix, hip-hop, and much more.

Life+Times: Throughout the book you talk a lot about Led Zeppelin, The Who, Eric Clapton and others, saying those bands were a major influence on you.

George Clinton: In the rock era, I was embarrassed that they knew so much about blues and I didn’t. And that was my mother’s music. That’s what really drove me to do the other music of the blues era, which was funk. They caught on to rock and roll to the point that everybody thinks white people made rock and roll and blues. That’s how early we gave it away. Once they split the stations up, the next generation didn’t even know that rock and roll was Chuck Berry, Little Richard and a lot of doo-wop groups. I said I wasn’t gonna let that happen with funk. I chose mid-tempo music which was a little slower than Motown even. Motown was funky as hell but they had pop overtones with the writing. I said I was gonna do New Orleans-style, old country, mid-tempo, funky music that makes you wanna shake your ass and go home and make love. That groove music. I used that music to talk political, social and love on songs. Nobody was leaning on that. Every now and then you got a dance record but they wouldn’t call it funk, it would just be a funky record. Ray Charles‘ “What I Say,” James Brown was funky as all hell but they didn’t say the word funk with the kind of elation that I wanted to put to it. I wanted to raise it to the level of rock and roll, to the top of the charts on its own without changing to dance music.

L+T: You also refer to Jimi Hendrix a lot.

GC: When I was living in Newark, I used to go to all the clubs in the village. I remember when he played with King Curtis, the Isley Brothers and he was always “the dude with the tuxedo on and no shoes,” that’s what you remembered him by. After he went to Europe and came back with Are You Experienced? that let me know he made some sense out of what I had seen The Who do with instruments and feedback. I had heard the feedback and understood the energy, but he took that stuff to church. He made that “noise” almost religious, sexual, he played it to where you had to accommodate that sound in your music after that. They’d have speakers that give that feedback because kids love when they get on older people’s nerves, so rock and roll came in like gangbusters and when Jimi Hendrix did Are You Experienced? it was open. We had a young guitar player, I just bought him those albums. I loved to work at Motown, but I just taught them over the next two or three years what they were doing with the feedback and by the time we did Free Your Mind…And Your Ass Will Follow, we knew what Jimi Hendrix was doing. There were 10 of us doing that, so they thought we were really crazy. He was crazy being one black guy with two white guys, but here you got 10 guys. They were scared as hell of that but that’s what we were into, funky, loud Motown I call it. Then we changed it to Funkadelic.

L+T: Between Parliament, the Parliaments and Funkadelic, creatively and musically, which was your favorite era to be a part of?

GC: I guess it would be Funkadelic because it would allow me to do anything. Funkadelic didn’t have any boundaries, I could actually do a Parliament record on Funkadelic. The guidelines weren’t strict since you’re not trying to get a pop single or hit record every time. Parliament I did trying to get dance hit record singles like “Flashlight.” We got lucky on Funkadelic with “One Nation,” but most of the time I’m not shooting for a single. So I guess it would have to be Funkadelic. But being a songwriter coming from Motown and Jobette, I’m in love with songs. If it was up to me, it would have been a doo-wop crew singing love songs and stuff I did with Bootsy [Collins]. I would have been doing more of that if it was just my personal thing that I like doing.

L+T: You talk about having 30 and 40 people as part of the groups, and between 1970 and 1980 you all put out almost 40 albums. How were able to manage all of those different artists and get the most out of everyone creatively?

GC: First, we were a singing group with a band, Parliament and Funkadelic. Then you have Bootsy which was a band, and the horn players Fred Wesley, Maceo Parker. Once you’ve been in James Brown’s band – probably the best in the world with organization, taking orders and giving orders – between Fred, Maceo and Bootsy, that was enough help. They are very likable people, all of them are so disciplined. Then Junie Morrison who came from the Ohio Players who did “One Nation” and was a super-genius writer, he’s good at putting stuff together. So working at Jobette and doing the Motown thing, I knew how to separate producers, writers and musicians. It was a family, it was just a matter of keeping it, picking the songs, choosing who gets what. It was a thing of having everybody be a part of it, we all would be on each other’s songs depending on whose record was getting ready to come out. Parliament was Funkadelic’s background singers; Funkadelic was Parliament’s backing band. We were all a family so it was easy for me to just be the referee so I didn’t have to oversee everything. I could say, “Maceo get the band ready, Junie get the band ready, get the girls ready, Fred and Bernie [Worrell] ya’ll write the charts.” I could just allocate. It’s only when you get to that point that record companies start to come in fishing for the talent, then that’s when the problems [come].

L+T: You said you wanted to make sure you wrapped the political statements in humor to put a cloak around everything, because “saying too much was the kind of shit that will get you killed.”

GC: When you get fucked up, out there with a microphone in your hand talking to a thousand people every night, they’re not gonna let you get away with just being up there preaching. Not unless you’re extremely good at being able to articulate. Chuck D was the best I’ve ever seen do it. If you got him on the microphone in front of the public, he could actually explain what he’s talking about. Most people you can’t because you say that shit out of emotion. You might be right, but people are scared of that much truth all at once. With a microphone, you can start riots, you can get people killed doing that, so we always stayed away from it. In the real sense, I don’t know no answers to shit. I can give you my belief or what I feel, but when you’re on that stage people think you’re God. I tried to keep it humorous but make people think. I may have a belief but I won’t put mine out there because it might change next week. If I done convinced a thousand people to go that way and I change my mind next, then what am I gonna do about that then [laughs]? So I tried to stay away from that. We’re high as hell, what the fuck do we know? I wasn’t taking none of those chances. I would always say, “Ain’t nothing but a party.”

L+T: You’re one of the most sampled people in hip-hop. In particular, tell me about the first times you remember hearing Dr. Dre’s The Chronic and Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle, which really pioneered the G-Funk era.

GC: That was no surprise to me. I did that with them. They were already doing it on the East Coast, so by the time it got to the West Coast, I did Doggystyle with Snoop the very first day they decided to do it. The sample is on there, but I actually did that one live the same way I did “You Can’t See Me,” with Tupac. When I first heard them, they liked the “One Nation,” “Knee Deep,” “More Bounce To The Ounce,” they liked the synthesized versions of Funkadelic and Parliament. That was different and closer to us than the East Coast. The East Coast used little samples, very few of them used loops. Public Enemy or Rakim, you heard a lick of yours in the record but it was just the lick. They had a lot of complicated arrangements, especially Public Enemy. You didn’t put Parliament or Funkadelic on them easily when you heard them. When you got to the West Coast, you could hear it “Atomic Dog,” “Knee Deep,” and “One Nation.” When Chronic came out, Dre used the whole record. He didn’t even sample, he just put the record on and rapped over the top of it. I was always down with that happening. I knew if I stayed connected to them I wouldn’t have to worry about the obsolescent part, which means you done got too old and you’ve got to get outta here: “If I play it right, I can just get in with them as opposed to being upset.” Otherwise, the only time you’re gonna hear your music on those packages on TV where they’re selling everybody’s music in one package.

L+T: Terrestrial radio was a major factor when you were coming up and it broke a lot of your records. How have you seen the game evolve with the internet today?

GC: That’s the only way you’re gonna do it unless you’ve already got power with the radio and your company is already in with radio. That’s very selective, that’s a small club right there. Today, you’ve got internet and social media. You’ve got to do that, that’s the new place to break records. People are personal with their iPhones and listening devices so you’ve got to use social media and find new ways of getting your record out. I’m putting a new album [First You Gotta Shake The Gate] out with 33 songs on it. The title [of the book] is actually the lead single from the album, “Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard On You.” If you take a picture of the book you can get it on your phone and four other songs. Those are the things you have to do. It’s a very small, selective club to get on radio.

L+T: Why was this a good time to put the book out?

GC: When you get to page 379, that’s the whole reason for doing the book period, right now. I don’t feel like – I ain’t finished, I’m still having fun, so I wouldn’t have been thinking about putting out a book if I hadn’t been fighting this long-ass lawsuit about copyrights. At first it was just the royalties, but now it’s gone into them trying to take the copyrights from my heirs and my family. It’s one thing to take the money back then when I was out in the streets acting wild, I can take the blame for that shit. I was a crackhead, you know, but now they’re trying to take the copyrights itself. They got away with hundreds of millions of dollars in the sampling era. I’m talking about the record companies, not the artists. The artists got suited and they thought I did it. I never suited anybody for it, matter fact I tried to get in touch with he artists to let them know all they had to do was call me as a witness and they’ll drop the charges, but I could never get through. So the main reason for doing the book starts on page 379, that’s Jane Peterer Thompson’s deposition in Switzerland. I haven’t gotten into to court for any of this shit except once, and I got “One Nation [Under A Groove]”, I got “[(Not Just)] Knee Deep,” and two other albums. Now my ex-lawyer is assisting Bridgeport Music, Universal and BMI in trying to get what we call the holy grail, “One Nation Under A Groove” and “Knee Deep.” I’m in the Supreme Court right now and I’m ready to get word out to the public. They get the message when I lose something in court, but never when I win something. ABC in Detroit and the New York Times both filed motions to have all these documents unsealed and we were on a roll we thought, but then they went into a coverup situation. There’s so much money from all of the samplings in hip-hop, commercials and movies, now they’re afraid to let it come out because they did all this stuff under the table back in the ’80s and ’90s and didn’t pay these musicians.

Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard On You? is available now.