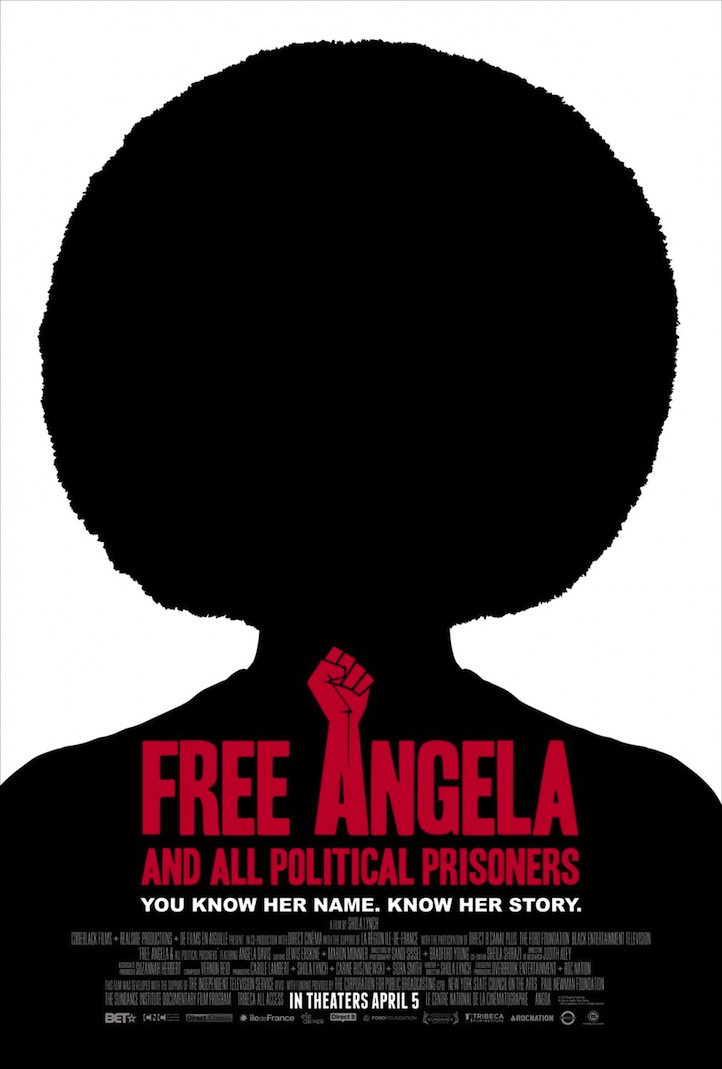

Director Shola Lynch Discusses Angela Davis Documentary, “Free Angela And All Political Prisoners”

03.29.2013

LEISURE

One of the most memorable names and faces from America’s radical movements of the 1970s is Angela Davis. Familiar as her name may be, few truly know her entire story. Such was the basis for Shola Lynch when she began piecing together her film Free Angela and All Political Prisoners.

“This is like digging in the crates, but about our stories, our history,” said Lynch, Free Angela‘s writer, director and producer. “I’m a woman – and a woman of color – and I know that we participated in making America all that it is. I want to know those stories; we should know those stories. We weren’t so passive in the creation of this country and sometimes we get a bad rap. Yes we were enslaved and then we marched, [but] our role was far more active. We are survivors, we are agents of change and I love those stories, and I think we need reminding of them of people of color and as women.”

After making rounds through at film festivals, including last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, Free Angela is set show nationwide April 5th in AMC theaters in New York, Chicago, L.A., Washington D.C., Oakland, Philadelphia and Atlanta.

Life+Times spoke with Lynch about her film and the life of Angela Davis.

Life+Times: How long did it take for this entire thing to get to this point?

Shola Lynch: About eight years. It took about a year to talk Angela into it – something close to a year, about 10 months – then you start the fundraising process. It’s funny, when it’s done, people are like, “Oh, that must have been so easy to raise money for, it’s so obvious,” but before the work exists, when it’s paving new territory and this film is – in terms of Angela Davis’, Black Power, the crazy late ’60s-early ’70s, the feeling that the revolution is around the corner – there hasn’t been much work done on that period. So, it was difficult to raise money for. I had to go to France to get about a third of the budget. I raised maybe 20-25 percent here, then by some miracle was connected with French producers who were like, “Oh, we can raise money in France,” and they raised about a third of the budget. Then I was able to come back to the U.S. with that amount raised and finished raising the rest. That’s when BET came on board, then as we were finishing, it became clear that we needed even more money because of licensing. Here’s the really interesting thing: it’s all owned by corporations these days, so that’s where Jada Pinkett-Smith came on board through another producer, and she brought in her husband and Overbrook [Entertainment], then they got JAY Z up in the mix with Roc Nation, which is pretty exciting.

L+T: Why was it so difficult at first to raise money and why would it be easier going overseas?

SL: They’re not afraid of political radicalism and Angela Davis is a difficult character in that sense. She asks questions that make us really nervous. She had joined the Communist party in the late ’60s, she was for Black Power and for people power, really. It was not just race, it was gender, it was class equity that she was interested in, and she spoke out on all of those things which made her deeply unpopular with the government at the time. Vietnam is happening, she’s a communist, she’s a professor at one of the best institutions, UCLA, and the governor of California – Ronald Reagan at that time – was really not happy with the fact that she was appointed to be a professor in the philosophy department, so that kind of started giving her this platform for her politics because he kept trying to fire her. It spiraled from there into a politically motivated kidnapping of a judge. It gets complicated and heady in that way. The ’70s is amazing, folks are trying to figure out justice means, how it works, were the people protesting or not, and this is happening with the Civil Rights Movement, [moving] into the Black Power movement into the Black Liberation army; it’s happening with the Students of Democratic Society and the split off into Weather Underground. It’s happening across the board for young people, whether they’re anti-war, feminist and whether they’re interested in racial power and equity.

L+T: The tag line is “you know her name, now know her story.” Why did you want to tell this story and delve further into her story?

SL: We know of her. Here in New York and when you’re on the West Coast, in the summertime, there’s always someone rocking an Angel Davis t-shirt. Her image is known. Her face and name is known, but we don’t know her story and it’s only these scant details. So, why has she become so important as an image? What’s the story behind that image? How do we add that third dimension so she’s not just two dimensional and flat? What is the story? How did she become an international political icon in the 70s? Those are the questions I went in with. I had heard her speak, I knew her name, I knew she was an activist and she was powerful, but what was the story that catapulted her to this place? How was she on the FBI’s Most Wanted list? What happened? I felt like it was useful to go back and investigate that, and for me, I thought it was really important to have her tell her part of the story, not just retread misconceptions.

L+T: What’s her role in the film and what’s her been reaction to final thing?

SL: As a director, I was pretty upfront that I have to have creative control [laughs], and she’s an academic, so she understood that. Basically, what she did is she said yes, “I’ll consent to an interview and I will be on board for the project.” That was what she did, she gave me an opportunity and it was up to me to make something of it. So, she didn’t hurt me and she didn’t help me. I now could say, when I talked to other people [that asked], “Are you gonna interview Angela? Is she on board?” Yes. That opened up certain doors. It got me access to her FBI files in a fuller way. Essentially, with her being on board, I got access, but she didn’t say, “talk to this person, do this, here’s my rolodex.” She was not in the editing room. She feels like the film is true to the time, the feeling of the time and the politics of the time, but it’s not a story she would tell in the way that I told it because I’m interested in her as the woman, and she’s always deflecting, she always wants to talk about other people. If she made the film, she wouldn’t have really spent time on her relationship to George Jackson and political prisoners. This is a political crime drama with a love story in the middle of it. You don’t get that kind of richness in material very often, and she would have totally downplayed it like she tried to in the interview [laughs]. When you see the film, it took us awhile to realize how much she was giving us because it wasn’t always with her words, it was with her gestures. For instance, when she talks about George, she kind of fixes her hair a little bit – that’s something a woman does, it’s a reflex when they’re talking about somebody they’ve cared for deeply.

L+T: What kind of footage did you use to tell the story?

SL: I used interviews, archival footage, photographs, headlines, FBI files. I tried to recreate the feeling of the time. There’s no narration, it’s a style I call historical vérité – in a vérité documentary, you’re with the character and you use the footage that you collect as you’re with the character, you see the transformation. Often with historical documentaries, they’re heave on narration. We don’t have that kind of narration, so this is historical vérité, I want to take you through the moments and choices and actions that she and other people are making through the story. I also shot original material. There are many scenes where she is on the run or she is in the jailhouse where there is no footage. So we created the images; I worked with Bradford Young, who’s best known for his work on Pariah. He also shot Middle Of Nowhere, [directed by] Ava DuVernay. He’s a total up-and-comer and he really got what I was trying to do in terms of creating impressions. I hate to use the word “recreations” because that conjures ugly, shaky-pan, TV-style cinematography, but what we did is we created the visual impressions that we wished we could find.

L+T: And her niece is in it?

SL: Yes. Eisa Davis played Angela. It’s not really about her face, it’s more about shadows and silhouette. They are suggestions of what’s going on in the scenes. [For instance], in the trailer, the afro silhouette, that’s Eisa, we created those images. Those were not archival. So what we do is we try to seamlessly mix a collage of images. And it is not easy to make it all work! But I feel like we did.

L+T: What was your most fascinating discovery about Angela, and who was the most revealing person to interview?

SL: That’s a tough question. I was surprised at the depth of the love story in the middle. I was surprised at her consistency and integrity in her story. Usually when you work on something for so long you find chinks in the armor, and she’s just really consistent with her point of view on this story. I was surprised by the governments insistence – I wish the prosecutor had been alive so we could talk to him about how his case came together, the motive that he was interested in. What I love about this period is how people are trying to figure out what justice is, figure out what it means in practical terms, how to make the world a better place. Politics was a part of their lives at that time. It’s not separate. Now, we vote, we may be into an issue, but we’ve forgotten to integrate our activism into our lives and when you do that, things go astray politically, socially, culturally. I think each person we interviewed revealed something new about her in the story, and we constructed it that way. Sometimes the main character is not the person to tell you everything. We knew that certain characters could give us what we needed to help the narrative flow forward. So, everybody played a part. Everybody that’s in the film helped us tell the story and added significantly.

L+T: How important was her afro to this lasting image of Angela Davis?

SL: I think her afro and her beauty is definitely a part of that, and [have] sometimes gotten disconnected from the politics; her politics were aligned with the kind of radical movements that were happening at that time. She’s not separate from that and, somehow she’s become separate from that. I think that she, like a lot of young women, were rocking afros. There was Kathleen Cleaver, Elaine Brown the women of the Panthers. This was the style, she was certainly not the only one, and her focus was never her hairstyle. She was going along, that was the cool thing to say: “you know what, [the] time is now for change. I’m not going to stand down.” Think about it: an afro is large and firm and obvious. That is a symbol of “I am here. I am powerful and I am not going to stand down,” and the folks at that time were acting that out in their lives.

L+T: Talk about the soundtrack and score for the film.

SL: Like any other movie, the heroes and heroines need a them song, so the music was very important. Vernon Reid knocked it out of the park. We licensed one song from Max Roach‘s estate. It’s a Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln song from their album We Insist!, and Abbey Lincoln had this scream that is insistent and terrifying and musical that says something about that period, the kind of conflicting feelings that young people, the government, everybody is feeling. Then we had Vernon Reid on board because for Angela, I kept saying guitar because it can be hard and insistent, and it can be so sweet, shy and beautiful. And Vernon, he’s a sensitive dude, man, and he’s really intellectual! He took in all this information and he helped create a really wonderful theme song for her and soundtrack for this story. He rocked it.

L+T: With all that’s made about prisons and the amount of African-American and Latino men and women that imprisoned, talk about the timing [of the film] and the relevance of her story still today, decades after it happened.

SL: Absolutely. The period from ’68-’72 is Angela Davis becoming Angela Davis the icon. There are two things in her life that cause her problems and give her this huge public platform. One, she chooses to become a communist and join the Black and Brown collective of the Communist Party in L.A; then two, one of her main focuses was political prisoners. She was very interested in George Jackson and the Soledad brothers and framing them as political prisoners. These guys were in prison for petty crimes [and] had been in prison for ten years. In that time, [Jackson] had become radicalized, he was reading, he started educating himself, he wrote a book. Through that connection and through worrying about that case, that Angela becomes very involved and becomes a spokesperson for political prisoners. At the time – you have to check the statistics – the numbers were still though in terms of people that were caught up in the prison system. That’s the beginning of that critical that movement of resistance around prisons. It’s crazy to think how exponentially the prison system has grown and has become the prison industrial complex. So yes, there are things in this story that are absolutely relevant today. The other thing that I think is relevant is that the government decides that she’s a terrorist without the proper evidence. Who are we calling terrorists? What’s the difference between national security and a person trying to speak their mind? That’s also a good question. She was acquitted, but a lot of people remember her as guilty.

Free Angela And All Political Prisoners opens in select theaters on April 5, 2013. Click for more information about the film and to pre-order tickets.