Director Bill Siegel Discusses Documentary “The Trials Of Muhammad Ali”

09.03.2013

SPORTS

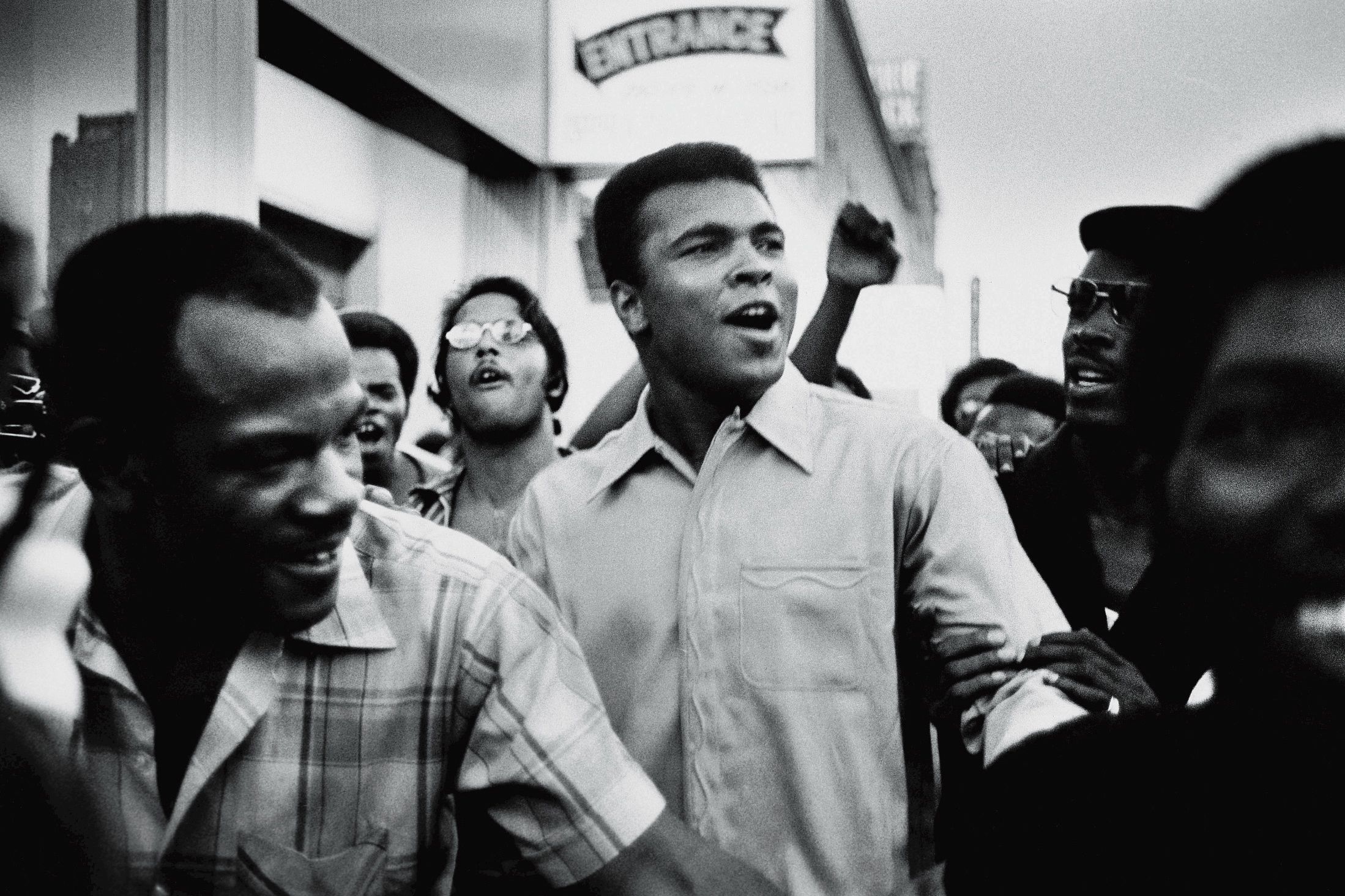

Without question, one of the most revered sports heroes and American icons of all time is Muhammad Ali. As is the case with almost all figures of similar transcendent stature – Jackie Robinson, Martin Luther King, Jr., etc. – complex individuals get whittled down to simplistic symbols. Thus, director Bill Siegel’s latest documentary, The Trials Of Muhammad Ali, serves to make sure that Ali’s entire story gets its just due, not just the persona he’s come to symbolize. “This is an Ali story that people don’t know about and need to know,” said Siegel. “People [can] really take away something for themselves that’s worthwhile beyond only watching a film to be entertained.”

Ali’s triumphs as a boxing champ are well-known, but his numerous stands against the American government – changing his name from Cassius Clay, embracing and becoming a devout member of the Nation of Islam, and refusing to fight in Vietnam, in particular – are often brushed over too quickly. Siegel’s film hones in on just that and is making its rounds across the country to spread the story nationwide.

Life+Times recently got a chance to speak in depth with Siegel about his documentary, The Trials Of Muhammad Ali.

Life+Times: What drew you to doing a film about Ali, and why did you choose to focus on studying his period of exile?

Bill Siegel: My first gig in documentaries was about 20 years ago on a six-hour series on Muhammad Ali. I was a researcher. I wasn’t directing that film. I was just out of school basically. I could tell that that film was going to be another boxing highlight film – and rightfully, most of the treatments on Ali focus on his exploits in the ring –but I felt like there was a story that needed to be told that focused on his life beyond the ring. Even then, I was drawn to the footage of him speaking on college campuses. At that time in my life, I didn’t really know that Muhammad Ali, and I think that [particular] Muhammad Ali, over time, has become increasingly forgotten, overlooked or undiscovered by generations coming of age now. If I could do anything to help rectify that and bring the righteous, humane, incredible beyond-the-ring back to the consciousness, I wanted to do that. That’s why I made the film.

L+T: Talk about research that you did and how you got some of the incredible footage and photos that are in the film.

BS: I’m a research geek [laughs]. On that project 20 years ago, that’s all I was doing. My job was to find the stuff, right? So I spent a year just immersing myself in archival footage of Muhammad Ali, so when I got to my own project in earnest about eight years ago, I had seen so much of it. I knew it was out there, I just had to go back and find it again. Also, in the process of doing that, I was working with a team. First of all I was working with Kartemquin Films in Chicago who are legends, and my independent team – a woman named Rachel Pikelny produced the film; Aaron Wickenden edited it. Rachel did a lot of her own archival research and turned up stuff that I hadn’t seen. I thought at that point, I’d seen it all, but the David Susskind footage that opens the film, I had never seen that before it blew my mind. As soon as I saw it thought, “Man this is how the film starts,” so it was a combination of material that I already knew was out there from past experience, and new eyes on the story. Rachel and Aaron were discovering the story like I did 20 years ago and they brought a lot of fresh perspective and new material to it.

L+T: Did you learn anything new about Ali this time around?

BS: A lot of what I learned was honestly seeing Rachel and Aaron discover the story the way I had, so they brought new juxtapositions and connections and emotions to the story development that really effected and impacted the making of the film tremendously. In terms of specifics, the Nation of Islam, as we were working on the film, became increasingly important to the story. Obviously I knew about the Nation of Islam, but I hadn’t planned going in to do as thorough of an explanation – as best I could as a white Jewish guy from Minnesota – of their world view. The Nation has been treated as a footnote in history, but no matter what you think about them, they’re remarkable. Their world view, I thought, needed to be rediscovered. So that was something that I knew about but hadn’t planned on being as important of a part to the film as it turned out to be.

L+T: It’s gotten a very positive response from the public so far.

BS: Yeah, it’s gotten great press. But even more importantly, it’s been a real diverse audience. Not just racially and ethnically, but generationally. I really think of it as a film for the whole family. That always sounds cliché and I don’t mean it that way – [recently,] it played at IFC here in New York, and there was a family that came in and brought their little guys. And I was so grateful that they understood that this is a film for tomorrow. It may come off as a historical documentary that looks back, but to me, it’s the past is present and really helps to form the future. So to bring the future into the theater to see the film has been the greatest thrill so far. I hope that continues.

L+T: Some of the people you chose to interview really stood out – Minister Louis Farrakhan, Abdul Rahman Muhammad (aka “Captain Sam”), who Ali met in Miami in 1961, and Ali’s brother, Rahman Ali, in particular. All of them were important figures in his life and are people who don’t get interviewed in most Ali films. How was it talking to them?

BS: Overall, it seems like there’s two camps of people: people who don’t understand why there would be another Muhammad Ali film, and people who do. They understand that this Muhammad Ali film had not been made. It was a battle to get the film funded for just that reason and there were a few great champions who understood that, “Nobody’s done this, this needs to be done.” So I knew all along that distinguishing this film from all the other treatments on Ali was necessary and I thought it was doable. Of course, the storybook is one way, but another way was the interviewees. I really wanted to limit the number of interviewees to an intimate group of people who were there: eyewitness, firsthand story tellers who were with Ali; his brother, his wife at the time, Mr. Farrakhan – who’s a peer of Ali’s – he’s a little bit older, but they came up through the Nation of Islam together, essentially – Captain Sam, who introduced him to the National of Islam. Also [interviewed], Gordon B. Davidson, the last surviving member of the Louisville Sponsoring Group, the white syndicate of Louisville millionaires who launched then-Cassius Clay’s career. Those people’s stories and perspectives hadn’t been included in most Ali treatments, and certainly not collectively the way they are in this film. Mr. Farrakhan told me – he was the hardest interview to get – nobody had ever done an interview with him about Muhammad Ali. That was amazing to me. His people told us we had 20 minutes with him and when we sat down, he gave us an hour. He was on, he was ready to do. Rahman, Muhammad’s brother, is just all love. He just radiates emotion. I think it comes through in the film, it was a very emotional time in his life. It’s interesting because if you really look at the film closely, you’ll see that Rahman appears in the archival footage probably 20 times. He’s right next to Ali all the time. We’ve become friends, he’s amazing. He’s Muhammad Ali’s brother so he carries some of the same DNA and humanity.

L+T: There’s a part in the film near the end where it talks about how Ali has been simplified into just a symbol. Obviously, the film works to get beneath that, but what do you think he’s come to symbolize and be simplified down to?

BS: Well if I’m allowed to have a favorite line in the film that I directed, it would be [writer] Robert Lipsyte who ssays, “We created a symbol and he’s come to be whoever we think he is and ultimately” – I’m not quoting him exactly – “There’s so much about Ali that’s more about us than it is about him.” At the end of the day, yes it’s a story about Muhammad Ali, but really it’s a story about us and how our perspective on him has changed because of how we’ve changed. That evolution is ongoing. I think that Muhammad Ali is an incredible through which we can discover ourselves and think about who we want to be individually. What kind of stand are you willing to take that would involve a serious level of sacrifice because you felt that the morality you have inside was more important than any fame or fortune that might come to you as a result of bowing down? Muhammad Ali didn’t do that, he didn’t bow down. He was ready to go to prison, he gave up his heavyweight title, he gave up his right to box. It’s hard to realize when it’s happening, when you’re making history, as he was, he thought he was going to prison.

Get more information about The Trials Of Muhammad Ali, include playdates and screenings, here.